Let us now praise famous men

How much sin is too much?

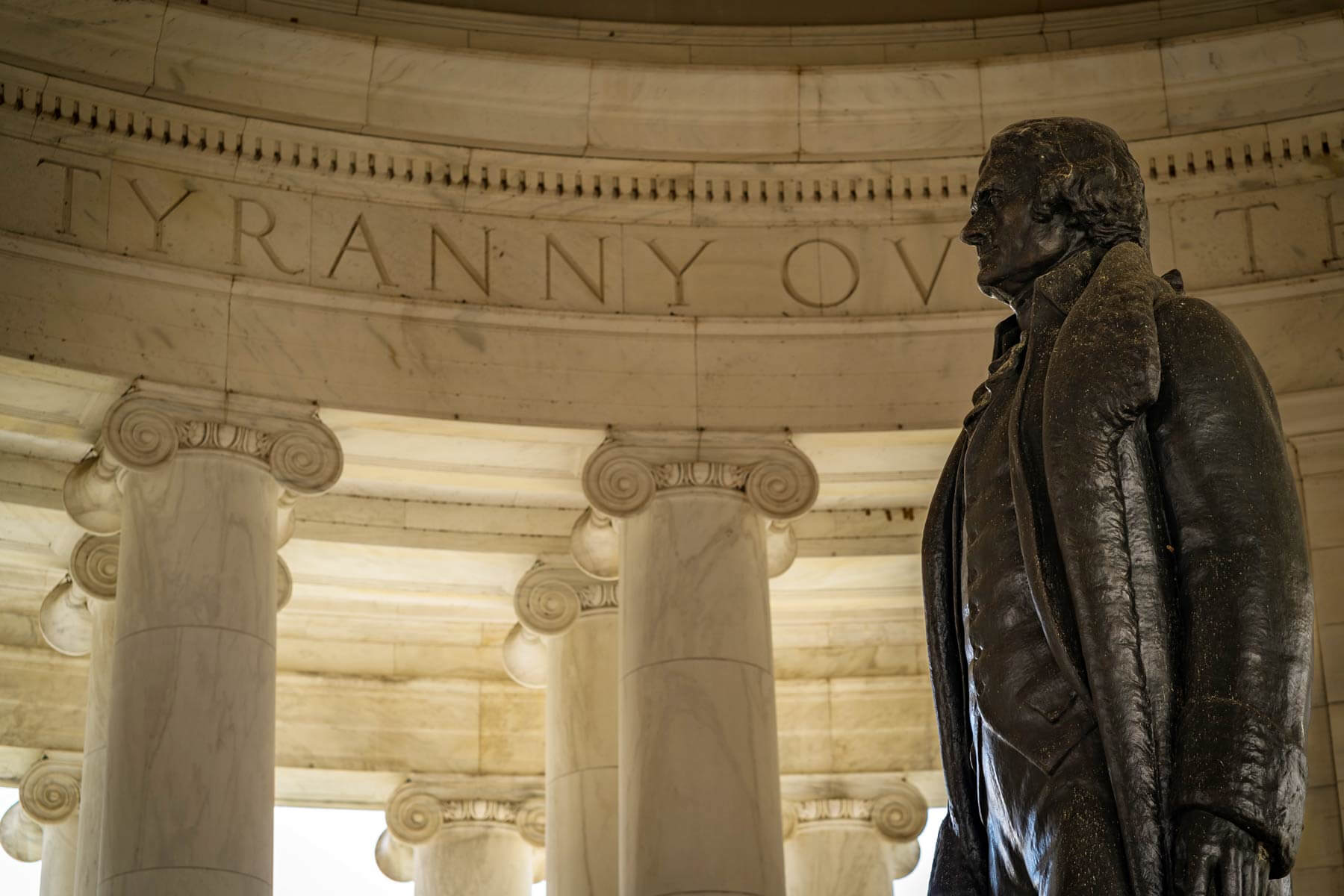

What a stupendous, what an incomprehensible machine is man! who can endure toil, famine, stripes, imprisonment or death itself in vindication of his own liberty, and the next moment be deaf to all those motives whose power supported him thro’ his trial, and inflict on his fellow men a bondage, one hour of which is fraught with more misery than ages of that which he rose in rebellion to oppose.

Thomas Jefferson Letter to Jean Nicolas Démeunier, 26 June 1786

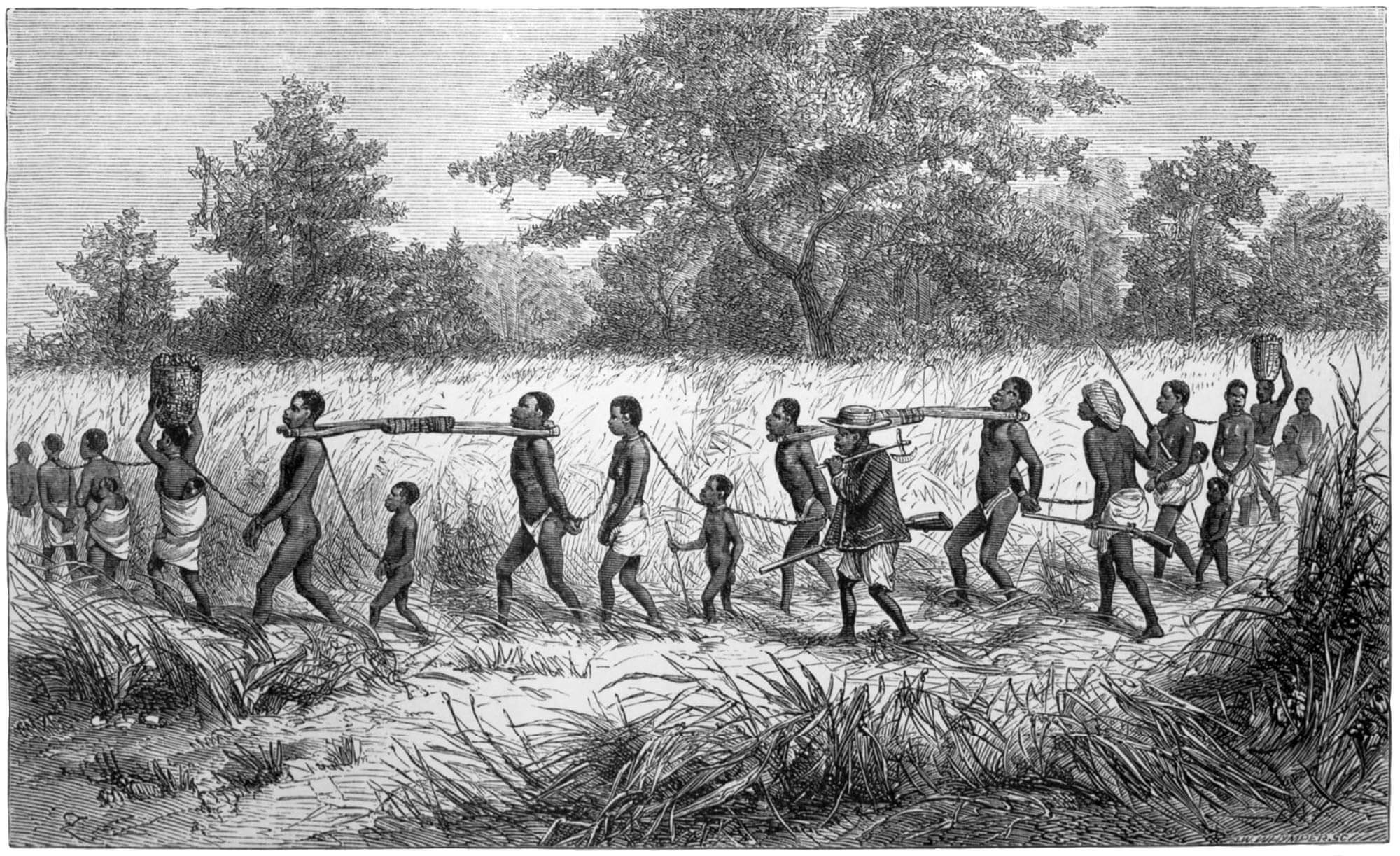

As old as history, as the written word, as the notion of civilisation itself, there has been human enslavement. The ancient Sumerian Code of Ur-Nammu contains legal statutes governing slavery, and surviving Hittite texts from Anatolia detail fugitive slave laws and rewards for their capture. Ancient Egyptians could find themselves enslaved through debt or parental servitude, or even sell themselves into slavery to escape starvation. The Greeks and Romans used slaves to build and run their empires, while Judaic, Christian and Islamic religious texts all endorse the practice. African societies traded in human bondage long before the Portuguese espied the Gold Coast, and Mayans and Aztecs had already forced countless thousands into servitude by the time the Spanish got round to 'discovering' them. The practice of slavery predates every European empire, and it was there waiting for them in their supposedly New World. Maybe the most peculiar thing about America's Peculiar Institution is how utterly commonplace it has been.

Tobias Rustat was a courtier to King Charles II of England. He fought with the Royalists in the English Civil War and helped Charles escape to the continent after their defeat and his father’s execution. His position with the King made him a wealthy man, and in later life he donated large sums to Cambridge University Library and to various colleges, not least Jesus College where his father had studied. He is buried in Jesus College Chapel beneath a plaque commemorating his largesse (over £2,000, almost half a million in modern money). He was, according to contemporary diarist John Evelyn, a very simple, ignorant, but honest and loyal creature

.

Tobias Rustat was also an investor in and director of the Royal African Company (as was King Charles II and his brother and successor James II). While the Company's original remit was a royal monopoly on the search for gold on the west coast of Africa, it quickly turned its hand to the more profitable business of human enslavement. Some 12.5 million Africans were taken from their homes and transported across the Atlantic, 1.8 million of them dieing before they reached the New World. The Royal African Company, according to historian William Pettigrew, shipped more enslaved African women, men and children to the Americas than any other single institution during the entire period of the transatlantic slave trade

(187,697 people, on 653 voyages between 1672 and 1731, 38,497 of whom died en route).

How much sin do you need to have before you come off the wall?

Sonita Alleyne, Master of Jesus College

Jesus College determined that the enduring presence of Rustin's plaque was incompatible with the chapel as an inclusive community and a place of collective wellbeing

. In March 2022 a Church Court of the Diocese of Ely, which holds jurisdiction over the Grade 1 listed religious building, denied their request to remove it. The past is a foreign country,

Judge David Hodge QC declared in his ruling, quoting J. P. Hartley, they do things differently there

. I would hope,

he continued, that when Rustat’s life and career is fully and properly understood, and viewed as a whole, his memorial will cease to be seen as a monument to a slave trader

.

How do we decide who gets to be understood and viewed as a whole

and who gets distilled to the essence of their mortal sin? Who gets a pass because the past was 'different'? Historians are not moral tribunals, but nor ought they to be apologists. They assemble facts and construct narratives, meaningful explanations of the past and, by extension, the present. I am less like a botanist in a forest than a woman arranging a few cut flowers for the drawing room,

declared C S Lewis. So, in some degree, are the greatest historians.

E H Carr concurred when he said that facts in history were like fish swimming about in a vast and sometimes inaccessible ocean; and what the historian catches will depend, partly on chance, but mainly on what part of the ocean he chooses to fish in and what tackle he chooses to use - these two factors being, of course, determined by the kind of fish he wants to catch. By and large the historian will get the kind of facts he wants.

The continual rearrangement of the past to suit current prejudices is … the historian’s work.

Ronald Steel

What kind of facts do we want? It's a buyers' market, as there are more available than ever before, from a wider range of suppliers, from the all-you-can-eat buffet to curated, artisanally-crafted nuggets of information designed to meet any need, to suit any taste. The White House began trading in 'alternative facts' in 2017, a phrase deployed by Counsellor to the President Kellyanne Conway during a Meet the Press interview in 2017. Back in 2004 journalist Ron Suskind told of another adventurously subjective assessment of truth, based upon a conversation with a staffer from the George W Bush administration: The aide said that guys like me were 'in what we call the reality-based community,' which he defined as people who 'believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.' [...] 'That's not the way the world really works anymore,' he continued. 'We're an empire now, and when we act, we create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality—judiciously, as you will—we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out. We're history's actors...and you, all of you, will be left to just study what we do'.

.

For all this, there is truth - what, to the best of our knowledge, we can say happened - and there is not truth. And yet even within the supposedly safer confines of the former category, as Carr says, we are still at liberty to choose the facts, the truths, that we want, the ones that support the position we wish to take, or confirm the beliefs we find most comfortable. Tobias Rustat was a slave trader. This is true. He profited from, and contributed to, murder, kidnapping, rape and enslavement, to one of the vastest and most enduring enterprises in human bondage and misery in history. If these things happened in war, in modern times, we would call them war crimes. But they happened in peace, so we can call them business, and Tobias Rustat a businessman, a benefactor, a philanthropist, a pillar of society. That was then. Times change, and standards with them. Can we judge the men and women of centuries past by the moral values of today? And if so, to what end? They are beyond remorse, or retribution.

The analysis of memory, as practice by historians, is moral in the sense that historians are, in effect, burdened with responsibility towards the dead.

George Caitlin

What of their own moral values? The men and women of the past were neither blind nor stupid. Slavery was an atrocious debasement of human nature

according to Benjamin Franklin. Nothing is more certainly written in the book of fate,

wrote Thomas Jefferson, than that these people are to be free.

You may choose to look the other way,

British Abolitionist William Wilberforce urged his fellow Members of Parliament in 1791, but you can never say again that you did not know

. Slave traders, and the societies in which they lived and operated, had moral sensibilities. They were, in America and Britain, for the most part Christians, but of course their texts were littered with justifications for and defences of slavery: The tree of Abolition is evil,

preached the Reverend Henry Van Dyke in the First Presbyterian Church, Brooklyn in 1860, and only evil—root and branch, flower and leaf, and fruit; that it springs from, and is nourished by an utter rejection of the Scriptures.

From the Spaniards of the sixteenth century through to the Americans in the nineteenth, slavery was a necessity, the steep and rugged pathway by which the Christian might bring the savage to God. And yet the outcome was rather to plunge the civilised man, the slaveowner, into ever-escalating acts of savagery and violence. When Jefferson looked at his peers in Virginian high society, he saw men whose moral instincts had failed them in the context of their own community, their own customs, their own property. Their wealth, their identity, and their security were sunk into the institution of slavery, the wolf they had by the ear and which they could neither hold nor safely release. The slaves were too degraded, lacked the moral capacity to be free men, but as Jefferson write to his friend Edward Coles in 1814, slaveowners could not acknowledge that this degradation was very much the work of themselves and their fathers

. Slavery was a moral evil from which Jefferson wanted to save American society, but he could see no way past it, either politically or personally, and could only look to future generations to redeem and perfect their unfinished revolution.

Of course it was different back then, but both slavers and enslaved were people, and knew one another as such. The very same argument that slave owners made to justify depriving others of their liberty – that they lacked the moral sense to govern themselves as free members of a republic – we now deploy to absolve them of their guilt: they knew not what they did.

There has never been a reckoning. Neither Britain nor America have experienced the kind of traumatic enforced regime change in modern history that might allow for a national reassessment of the past, a reset of attitudes and economic structures that have prevailed for centuries. They have evolved for certain, but in the absence of an extinction-level asteroid strike, it is as though the DNA of the dinosaurs persists within their cultural discourse, a pernicious continuity that inhibits honest appraisal of either nation's history.

It is this lingering strain of complacency and entitlement that enabled Britain's Prime Minister Boris Johnson write, in his journalistic days in 2002 of Africa, that the continent may be a blot, but it is not a blot upon our conscience. The problem is not that we were once in charge, but that we are not in charge any more.

It is the obliviousness to the existence of other narratives and the lived experiences of other peoples that encouraged establishment historian David Starkey to deplore his contemporaries 'going on about slavery' and to declare that Slavery was not genocide, otherwise there wouldn't be so many damn blacks in Africa or in Britain would there? An awful lot of them survived…

. And it is the knee-jerk veneration of the past that led then-Education Secretary Michael Gove in 2010 to stress the importance of narrative and biography in history teaching in schools: The current approach we have – denies children the opportunity to hear our island story. Well, this trashing of the past has to stop.

I would be taught all about whiteness, I would know well its gravity and its weight, I would be taught to worship slave traders and imperialists and lionise philosophers and politicians who believed me to be less than human.

Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire

The teaching of American history has been similarly politicised by the Republican Party in pursuit of electoral advantage: They're not trying to educate, they're trying to indoctrinate,

, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida fulminated against classroom teachers as he demanded the right for parents to sue any teacher or school that made students feel 'uncomfortable' on the subject of race in America's past or indeed present. The specific focus of this indignation was identified as Critical Race Theory, an argument put forward by legal scholars in the 1990s which sought to explain that the so-called American dilemma was not simply a matter of prejudice but a matter of structured disadvantages that stretched across American society

. Essentially this says that racism was more than a matter of individual prejudice, but that it was embedded within American society and institutions.

Critical Race Theory was, unsuprisingly, not taught in any American classrooms, but that didn't stop seven states from banning it anyway, (sixteen more states had legislative bans in progress as of mid-2022) as part of an all-inclusive legislative broadside against anti-Americanism, the 'woke' agenda and cultural Marxism. SB148, passed by the Florida Senate in March 2022, banned lessons or workplace training that could cause individuals to experience discomfort, guilt or another form of 'psychological distress' based on actions committed in the past by members of the same race, color, sex or national origin.

British and American society and history emphasise and celebrate continuity, stability, and tradition. Britain has a royal family and an unelected second chamber of Parliament, the House of Lords, and huge swathes of the country remain the possession of hereditary landowners, who continue to exert its attendant wealth and influence. American politics remains beholden to the beliefs and decisions set down by a group of men, many of them slaveholders, in 1787, and legal originalists, including a good proportion of the early 21st-century Supreme Court, insist that all Constitional matters continue to be interpreted according to the intent of this handful of long-deceased lawmakers rather than, for instance, any of the 330 million Americans who happen to be alive today.

The whole earth is the sepulchre of famous men; they are honoured not only by columns and inscriptions in their own lands, but in foreign nations on memorials graven not in stone but in the hearts and minds of men.

Thucydides, Pericles' funeral oration

It is not the job of history or of historians to determine the rightness or wrongness of this, merely to acknowledge it as the reality of Britain's and America's past, and thus inevitably of their present, and to recognise the influence this might exert upon the study and teaching of history. Do we gloss over the reality that Tobias Rustat and Thomas Jefferson were slave traders because this fact sits uncomfortably with their status as pillars of their respective societies (more like a titan in Jefferson's case)? Or that Rustat's investment in the Royal African Company was doubtless linked to that of his royal patron King Charles II, or that Charles's brother and successor James II played a significant part in kickstarting the English slave trade as a means of restoring royal finances after the disasters of the English Civil War and Interregnum? The lives that were lost or destroyed go mostly unremarked, but the fortunes that were made remain, often within the same families, the same institutions.

Why are so many American states legislating against an open assessment of their racial past in the classrooms? Why is the British government promoting such a narrow focus on great men (and, possibly, women) and grand narratives in their schools? And why, in both societies, is racism continuously presented as a moral failing on the part of mostly unnamed individuals, as a series of small anonymous crimes rather than a deliberate campaign of kidnapping, oppression, subjugation and murder, one that endured long past the formal end of slavery itself and which remains built into the foundations of their establishment and the distribution of wealth, power, and opportunity? The sins are swept under the carpet, diminished, their legacies downplayed or ignored, while the sinners are elevated, continue to be hung on the wall, enshrined in statues, venerated in the classrooms and idolised in grandiose memorials.

We can choose our own facts of course. But more often they are chosen for us, by people who perhaps do not have our best interests at heart. And lies of omission are still lies if they allow us to believe that the Founding Fathers were heroes and visionaries whose ideals of liberty should continue to shape their country and the world 250 years after they first committed them to paper. They are lies if they encourage us to believe that great fortunes are necessarily indicative of virtue and hard-work, that they have been 'earned'. And they are lies if they foster the impression that men of inherited wealth and privilege are somehow better, that their hands are cleaner or their motives purer, and that their outsized influence on modern democracies is anything their fellow citizens should wish to defend, to protect or to preserve.

This is just history. We'll do our best not to lie to you.

I am a straight, white, Christian, married, suburban mom who knows that the very notion that learning about slavery or redlining or systemic racism somehow means that children are being taught to feel bad or hate themselves because they are white is absolute nonsense.

No child alive today is responsible for slavery. No one in this room is responsible for slavery. But each and every single one of us bears responsibility for writing the next chapter of history ... we are not responsible for the past. We also cannot change the past. We can't pretend that it didn't happen, or deny people their very right to exist.

Mallory McMorrow, Michigan State Senator

Bibliography

- Akala (2018). Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire. London: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

- Cooper, A. D. (2012). 'From Slavery to Genocide: The Fallacy of Debt in Reparations Discourse.' Journal of Black Studies, 43(2), 107–126.

- Helo, A. & Onuf P. (2003). ‘Jefferson, Morality, and the Problem of Slavery’ William and Mary Quarterly, 60(3), July 2003

- Kahn, A. & Bouie J. (2021) 'The Atlantic Slave Trade in Two Minutes' [online] Slate. Available at: slate.com [Accessed 2 April 2022].

- Lawrance, B. (2019) '400 years’ anniversary of slaves arriving in America – does it matter?' [online] anti-slavery. Available at: antislavery.org [Accessed 2 April 2022].

- Suskind, R. (October 17, 2004). 'Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush'. The New York Times Magazine.

- Wallace-Wells, B. (June 18, 2021) 'How a Conservative Activist Invented the Conflict Over Critical Race Theory' The New Yorker