The city on a hill

Whose history is it anyway?

The position of the Americans is therefore quite exceptional, and it may be believed that no democratic people will ever be placed in a similar one.

Alexis De Tocqueville

American history is unique. There, we said it, and not just so you’ll persevere with this history of this nation and not one of the many many other national histories available. But how unique is it? Is it special the way we are all special, every one of us a beautiful and unique snowflake, or is it actually, as de Tocqueville says, exceptional?

There is a long and often politicised idea of American exceptionalism, from John Winthrop’s city upon a hill through de Tocqueville and the Cold War right up to the present day. It maintains that America occupies a singular position among the nations of the earth and that its social and historical development cannot be understood within any wider context, but purely upon its own terms. To deny American exceptionalism,

said Republican Presidential candidate Mike Huckabee, is in essence to deny the heart and soul of this nation.

I believe in American exceptionalism,

President Barack Obama concurred, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.

The idea derives in large part from the idea of America as an invented nation (or rather a re-invented one), a nation of immigrants who chose to live there (as opposed to the natives they killed to make room). In this narrative it was a clean slate, as were those who crossed the ocean to settle and tame its frontiers. The 14th Amendment to the US Constitution, passed in 1866 declared that All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

Regardless of where they or their families had come from, or in what circumstances, they were now Americans. In parallel with this notion of a self-made nation run equally powerful themes of Providence and of Manifest Destiny. America has lived on the verge, so to speak,

James Ceasar wrote, of a crusade

. A messianic streak pervades its political rhetoric, from the early Puritan preachers through Thomas Jefferson's Empire of Liberty and Abraham Lincoln's declaration that America was the last best hope of earth

.

The political, and increasingly national, identity of the early colonies and fledgling nation defined itself against the European empires which most of its population had left behind, from whose aristocratic rulers and feudal obligations they had freed themselves. The New World (not new) was a blank canvas (not of course blank, nor actually a canvas) upon which they could build something better, a way of life in which religious freedom (their religion) was enshrined, and private property protected. This philosophy, these values, and this destiny left little room for the people already living in the Americas. They were part of this great landscape the early settlers were faced with, this challenge they were given to conquer, to be adapted to, then overcome, displaced and all but erased by the inevitable march of progress. They had no right to a country merely because they were born here and then acted like savages,

writer and philosopher Ayn Rand declared to the West Point Military Academy graduating class in 1974. The white man did not conquer this country… Since the Indians did not have the concept of property or property rights - they didn't have a settled society, they had predominantly nomadic tribal "cultures" - they didn't have rights to the land, and there was no reason for anyone to grant them rights that they had not conceived of and were not using.

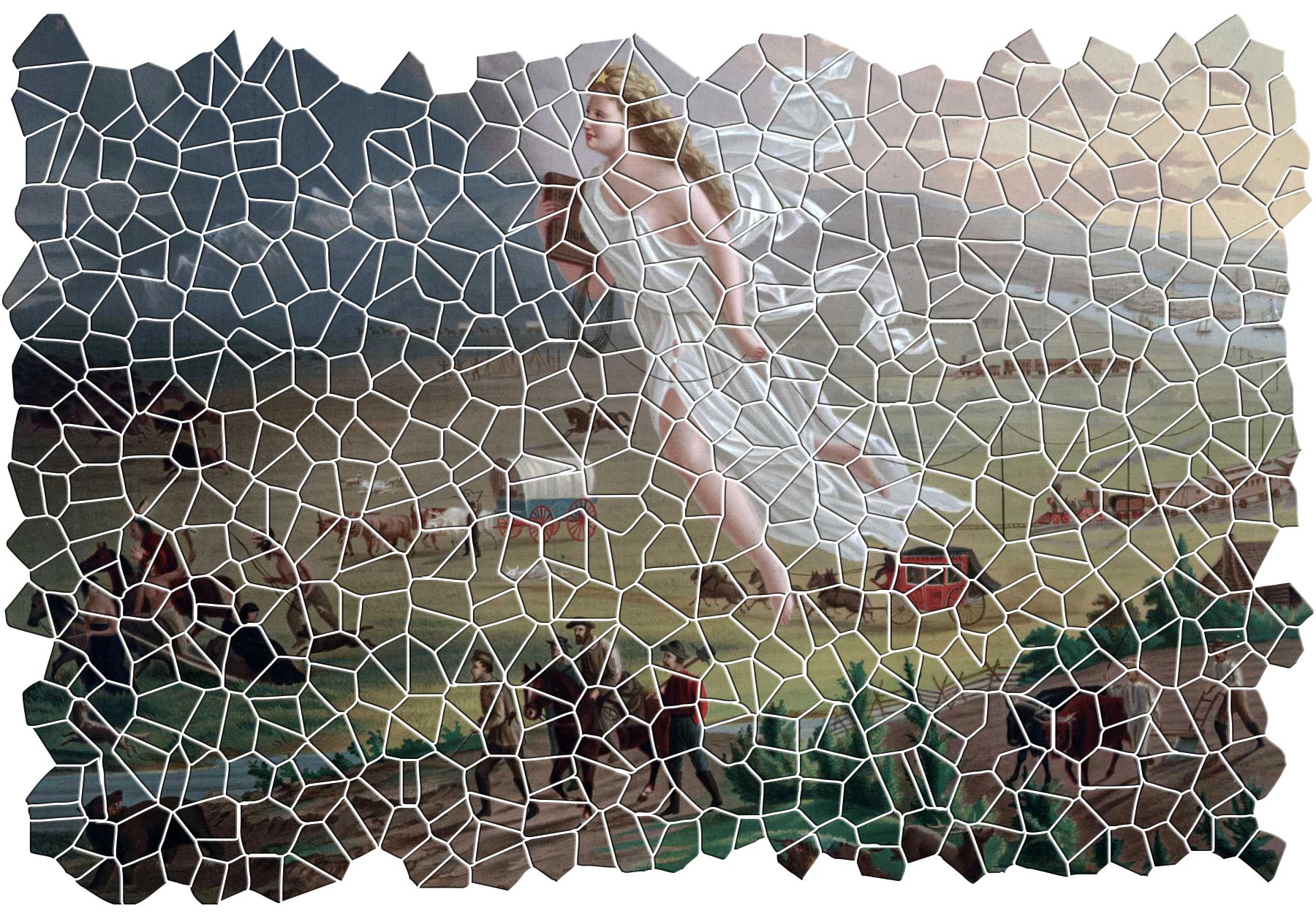

The idea of American history, that of an inevitable realisation of a natural, even divinely-ordained, outcome, is famously conveyed by the painting at the top of this page, John Gast's American Progress. Here we have the march of modernity, from east to west, the vanguard of frontiersmen (and they are all men) pushing back the primitive darkness, the wild animals and Indian savages both. Behind them come the the settlers, farmers, and the stagecoach, the railways, and in the distance the great cities, the bustling metropolis of commerce. Above them all floats the divine figure of American destiny, a homegrown variant of the ancient goddess Athena, or of Liberty: she is advancement, enlightenment, progress herself, and in one hand she bears the telegraph wires that will bind this nation together. In the other she carries a schoolbook.

This national myth, American exceptionalism, magnifies the perceived significance of recurring themes in American history (themes shared by numerous other nations). The obligation of citizens to obey a supposedly unjust government for instance, a drama enacted twice with very different outcomes in the War of Independence and the Civil War. Or the United States' obligation to mankind, to the rest of the world: should it come down from its hill and intervene in other countries to support various interpretations of liberalism and democracy, or should it lead by example, remaining above the fray and squabbles of lesser nations in splendid isolation? And perhaps most enduringly, the tension between the Union and its members, be they states, religions or ethnicities: is an American an American first and foremost, or are they a Southerner, or a Catholic, or a black person? It is no accident that Gast painted the schoolbook clutched tight in the right hand of progress, for it was in education, and in a shared understanding of American history that many hoped to construct the consensus of what it means to be American.

Nations, in other words, live and die by their myths.

Joseph Moreau

The past is messy. It resists easy answers or morals, and it's certainly light on lessons. It's full of sexism and racism, bad things happening to good, or at least blameless, people, and it continually reinforces that oldest of observations, that life isn't fair. Martin Luthor King may have said that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice

, but we may well ask, whose justice? Definitions vary, and may change over time.

History is, more often than not, the story a nation or group agrees to tell about its past. This doesn't mean it isn't true, but it's rarely the whole truth. For reasons of space, it can't be. A shared understanding of its past enables a nation to achieve a greater consensus on its present, and in this nation's case on what perhaps it means to be American? The question is whether that comes at the expense of diversity, of differing experiences of gender, class or race, of minorities and immigrants. Can history celebrate this diversity and at the same time promote a socially beneficial sense of unity? And should it?

On 18th January 1995 the United States Senate voted by 99-1 to condemn the new National History Standards syllabus developed by the National Center for History in the Schools. Only Senator Bennett Johnston of Louisiana demurred, and that was because he didn't think that the condemnation was condemnatory enough. The charge was one of political correctness, of placing hitherto marginalised voices centre stage at the expense of the canon of (entirely) dead, (mostly) white (almost exclusively) males, and moreover of bringing American history into disrepute. Our ancestors

wrote Professor David Saxe, are not presented as carving a new civilization out of the wilderness with sweat and blood, but rather as forcing the "removal of many Indian nations" and engaging "in abrasive racial encounters with Native Americans, Mexicans, Chinese immigrants and others in the West" (Ibid.) It is as if the history of the United States was one long race war.

This was history, but not as they knew it.

Leaving aside the 'doom and gloom', numerous establishment voices railed against the sidelining of the familiar, and significant, cast of 'great men'. It may be unfortunate that dead White European males have played such a large part in shaping American culture,

Arthur Schlesinger judged, but that’s the way it is. One cannot erase history.

Schlesinger acknowledged that American history was long written in the interests of white Anglo-Saxon Protestant males

, but that even so compensatory history, history that sought to redress historical inequalities through an unrepresentative focus on those who had most suffered from them, was bad history. The past was, for the most part, racist and sexist, and the upshot of that was that white guys called the shots.

There's an obvious logic to this argument, but history and the past are not the same thing. History is a study of the past that seeks to inform the present, and is inevitably shaped by present-day perspectives, preoccupations and values. This is why every generation writes its own history. This might sound Orwellian, but it's more a matter of editing, of emphasis. In the nineteenth-century for instance, American Indians formed a far larger part of standard national histories, until they made way for a fashion for longer-term political and economic developments. If our own times and our own cultures allow for a greater plurality of lives and experiences, then our histories can reflect this, can give a voice (even posthumously) to those so long denied one.

The multiethnic dogma abandons historic purposes, replacing assimilation by fragmentation, integration by separatism. It belittles unum and glorifies pluribus.

Arthur Schlesinger

Does this mean we all of us have our own history, our own (not to get too postmodern) truth? Schaun Wheeler wrote of the difficulties in engaging his students in a history that isn't written for me

, a history in which they saw no-one like themselves. A history written for an individual now seems possible, but where does this leave the national myth? Is this just genealogy, all individual and no society?

In 1903, W.E.B. DuBois sounded a note of caution against ethnic histories. The Negro who comes through the Negro college and studies Negro history under black professors; the child who comes through the Negro school with negro teachers, is going to grow up as a Negro and not as an American. He is going to hate and despise the civilisation that enslaved him, and now insults him. He is going to believe that the world of white folk is armed against the world of black folk, and that one of these days they are going to fight it out to the bitter end.

You could not smash history into a million little pieces and expect society to remain blithely intact.

There has always been a tension, a contradiction even, between the way our past is written and the way it was lived, or the way we wish it had been lived. In Bruce Goebel's words, When people speak of their heroes, the boundaries between history, ideology, and fiction are rarely clear.

Thomas Jefferson is an American hero, a Founding Father and the third President. Thomas Jefferson wrote the immortal declaration at the heart of the United States Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness

. Thomas Jefferson believed that black people were inherently inferior to whites, and could never live equally alongside them. Thomas Jefferson fathered a child with his black slave Sally Hemmings. Who was Thomas Jefferson? How could the 'Genius of Liberty' also have been a slaver?

As we said, it's messy. People are messy, rarely all one thing or another. Myths aren't real, neither are narratives and stories, less for what they put in than what they leave out. But national myths, national histories even more so, cannot hope to embody that shared understanding, those common values if too much of the nation has been written out of the picture. The myths of 1776, of 1865 or even 1945 do not speak to Americans in 2025, nor do the history books of those times show everyone alive today a past in which they can recognise themselves.

A critical reflection upon a nation's past, especially self-reflection, is not an attack upon its present, nor necessarily a cause for shame. George Santayana's widely-repeated quote that Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it

is a prescription for understanding and growth, for recognising how our ancestors dealt with the circumstances they faced, how their society worked, for better or worse, and the legacy they have left us, the foundations upon which we build. In John Oliver's words, History when taught well tells us how to improve the world, but when taught poorly falsely claims that there is nothing left to improve

. A national myth featuring the Puritans in a starring role surely warrants the warts and all

treatment.

I’ve spoken of the shining city all my political life, but I don’t know if I ever quite communicated what I saw when I said it. But in my mind it was a tall, proud city built on rocks stronger than oceans, windswept, God-blessed, and teeming with people of all kinds living in harmony and peace; a city with free ports that hummed with commerce and creativity. And if there had to be city walls, the walls had doors and the doors were open to anyone with the will and the heart to get here. That’s how I saw it, and see it still. That's what we'll try to capture. Bear with us.

Ronald Reagan

Bibliography

- Burks, B. (1997). Unity and Diversity through Education: A Comparison of the Thought of W.E.B. DuBois and John Dewey. Journal of Thought, 32(1), 99-110.

- Ceaser, J. (2012). 'The Origins and Character of American Exceptionalism.' American Political Thought, 1(1), 3-28.

- Cayton, A. (2002). 'Writing North American History.' Journal of the Early Republic, 22(1), 105-111. doi:10.2307/3124860

- Moreau, J. (2004) Schoolbook Nation Conflicts over American History Textbooks from the Civil War to the Present. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

- Sandweiss, Martha. 'John Gast, American Progress, 1872.' Picturing US History, American Social History Project, picturinghistory.

- Saxe, D. The National History Standards: Time for Common Sense. socialstudies.org

- Schlesinger, A. (1992) The Disuniting of America: Reflections on a Multicultural Society. W.W. Norton. New York.

- Turner, F. (1893) 'The Significance of the Frontier in American History.' Annual Report of the American Historical Association, 1893, 197-227.

- Wheeler, S. (2007). History is Written by the Learners: How Student Views Trump United States History Curricula. The History Teacher, 41(1), 9-24.