Cupboards bursting with skeletons

Set in a silver sea

This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle/ This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars/ This other Eden, demi-paradise/ This fortress built by Nature for herself/ Against infection and the hand of war/ This happy breed of men, this little world/ This precious stone set in the silver sea.

William Shakespeare, Richard II

Shakespeare sets the tone. As so often, he takes that familiar feeling of what you think you know and makes it succinct and accurate. It’s only flaw is that Shakespeare is wrong in almost every important respect.

Even the quickest look at history will tell us England has hardly been inoculated against war. As anyone will tell you from AD43 or the 860s, 1066 or 1215, to say nothing of the decade after 1800 and the summer of 1945. And that doesn’t scratch the surface of the conflicts we managed to breed for ourselves. Likewise the history of infection in England is sadly just about as long as it is anywhere else. Even ‘happy breed’ may be pushing things too far but, you know, mustn’t grumble.

George Orwell, himself no stranger to a big idea, picks up the thought:

England is not the jewelled isle of Shakespeare’s much quoted message, not is it the inferno depicted by Dr Goebbels. More than either it resembles a family, a rather stuffy Victorian family, with not many black sheep in it but with all the cupboards bursting with skeletons. It has rich relations who have to be cow-towed to and poor relations who are horribly put upon, and there is a deep conspiracy of silence about the source of the family income. It is a family where the young are generally thwarted and most of the power is in the hands of irresponsible uncles and bedridden aunts. Still, it is a family, and it has its private language and its common memories, and at the approach of an enemy it closes its ranks.

George Orwell, Why I Write (1946)

More prosaic, perhaps, but in its way no less romantic. Like Shakespeare, Orwell is growing his own pearls from a few grains of truth.

Both he and Shakespeare can be allowed to get away with it for the simple reason that neither are writing history. Whether it is for plays, sonnets or high quality allegorical novels, they are paid to make things up. The result is that both are spending their time on the idea of England; maybe even the ideal. Not its history.

And yet things are never that straightforward.

The idea of England - whether it comes from the painting on top of a biscuit tin or the nation of shopkeepers that sold it to you - comes from its history. The United States of America is all about the idea of what it could be: Ronald Reagan’s City on a Hill or the prospect of what lies at the end of Martin Luthor King and Barack Obama’s arc of the moral universe. In England it is all about projecting, and indeed measuring up to, what has gone before.

England can do this with its history because it has so much of it. In a world of nation states, few can trace a continuous line back so far that it ceases to be important just how long it has been. Greece, China and Persia, like England, cannot remember the problem that confronted leaders like Massimo d’Azeglio in the mid nineteenth century that ‘we have made Italy, now we must make Italians’. Even before the English, Roman Britain drew out largely familiar dimensions in the first century AD. It did not take long after the Roman departure for the influx of tribal invaders to recognise a common identity as Anglekynn and for the separate kingdoms to more often than not recognise one of their kings as Bretwalda. After the Viking invasions, only a north-south divide remained. Even then it was clear that - administratively at least - this was unsustainable. From then on England came as a job lot. Anyone taking charge would either set themselves up at a single top table or not at all.

This kind of continuity breeds both reputation and expectation. When Elizabeth I addressed the troops at Tilbury with 'the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too' it was a clear implication that for Spain to be the first to take England after all those years they would have to pull out something special. They didn’t. The idea stuck.

Ideas work best when there is something for everyone. If things were quite as exclusive as Orwell made out, someone would have felt the need to reset the clock long ago. English history, however, offered plenty for both us and them as well.

For a place that over the years has been at the forefront of trading, financial, industrial and digital revolutions, an awful lot of time can be spent gazing wistfully at pastoral idylls. There is flexibility in being able to pine both for heavy manufacturing industry and John Major's ‘long shadows on county ground [and] warm beer’ before he deployed a bit of George Orwell himself to conjure ‘old maids bicycling to communion through the morning mist.’ The small, plucky, underdog island can rule a quarter of the global and make sure that the lingua franca wasn’t French any more.

Nor are all of these ideas incompatible. You could run a global financial trading house with a copy of Constable’s Hay Wain on the wall without a moment’s pause. Turner’s Fighting Temeraire can show one instrument of England’s power and success being towed out for scrap under the steam of its immediate replacement, which now conjures a pride and nostalgia all of its own.

All of this comes back to the source material we are given to play with. A history of England will include Roman legions, knights and castles, before offering crusades, pirates, preachers, scientists and merchants, before racing up to date with industrialists and politicians, programmers and pop culture. It is almost impossible to do without bringing in just about every corner of the world at some point or another.

And this is where the truth becomes, if not stranger than fiction, then far more intricate, intriguing and enticing. In so many context, people made decisions, lived their lives and were who they were, not what it suited us for them to be. Those stories, with their mysteries, uncertainties and - yes - ideas give us all the history we can ask for.

It has been said that in America, if you can imagine it, it’s here somewhere. They have the geography, but we have the history.

Do we ever have that.

Bibliography

- Shakespeare, W. (approx 1595; 2011) Richard II. Oxford, OUP

- Orwell, G (1946; 2004) Why I Write. London, Penguin

- MacArthur, B. ed (1996) The Penguin Book of Historic Speeches. London, Penguin

- Armada Portraits of Elizabeth I (1590s). Royal Maritime Museum, National Portrait Gallery, Woburn House

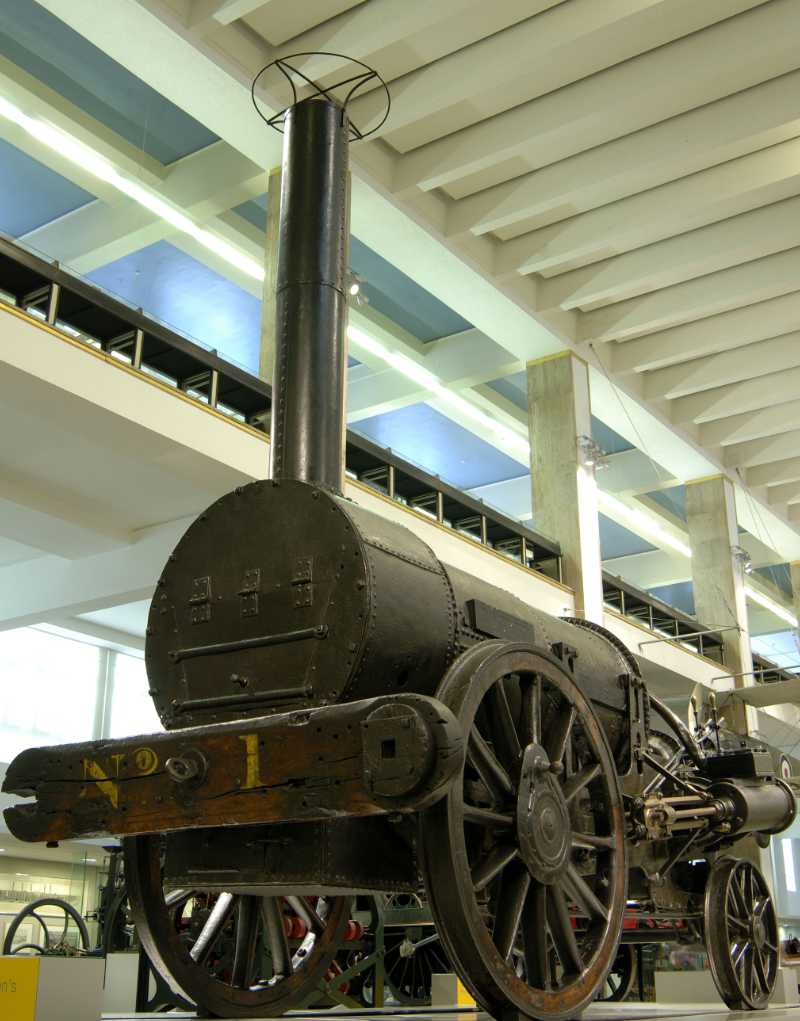

- George Stephenson's Rocket. At the Science Museum, London