The Devil is loosed

Richard Lionheart

Born 8 September 1157, Oxford, England | Died 6 April 1199, Chalus, Limousin

King, duke, crusader and captive, he made history go widescreen. Built castles, led armies, inspired wherever he went. Legend in his lifetime. Legend ever since.

King Richard I reigned for ten years, give or take. He spent no more than six months of that in England - four in 1189 preparing for crusade, and then two more in 1194 on his release from captivity. This section was nearly called the king who wasn’t there. Yet Richard the Lionheart is the only English monarch to earn an adjective since William the Conqueror. His statue stands outside Parliament. Sometimes its best just to get swept up in the story.

Richard’s courage, shrewdness, energy and patience made him the most remarkable ruler of his time.

Ibn-al-athir, Muslim historian writing c1230; even Richard’s enemies were impressed

Richard was Henry II’s second son to survive to adulthood. He was born in Oxford, but that is where much of his association with England ended. The 1169 Peace of Monmirail lined up Richard to become duke of Aquitaine, Henry’s large, rambling possessions in southern France which came to him through his marriage to Eleanor. Richard, Eleanor’s favourite of her sons, was invested with the county of Poitou in 1172. After the war with Henry, Richard received half the revenues of Aquitaine from 1174 and became duke in his own right in 1179 when he held the duchy directly from the French king rather than his father. Richard had been offered a trade of Aquitaine for England, Normandy and Anjou by his father on the death of his elder brother, Henry the Young King. He turned it down.

It was no soft option that Richard was taking. Aquitaine’s barons were used to semi-independence from their feudal lords and were infamous for pushing that as far as they possible could. Richard brought them swiftly into line. William of Angouleme, one of the most powerful, was made an example of. Richard sent him off on a crusade from which he did not return.

Before he was twenty Richard had reduced his vassals to obedience.

Sir Steven Runciman, History Today (April 1955)

It was already obvious that Richard had many, if not more, of his father’s talents. He could both build and take castles; he had a flair for soldiering and his men clearly loved him; and he had a keen nose for his rights - there would be little room for barons to slip things by him.

Richard also threw himself into the world of royal politics and intrigues, in the family feuding and on-off fighting with his father and the French king, Philip Augustus. A larger stage perhaps beckoned, as he took the cross in 1187. That soon became inevitable as news arrived of the disastrous battle of Hattin on 4 July, which had swept away the army of the Crusader States of Outremer and opened Jerusalem’s door to Saladin.

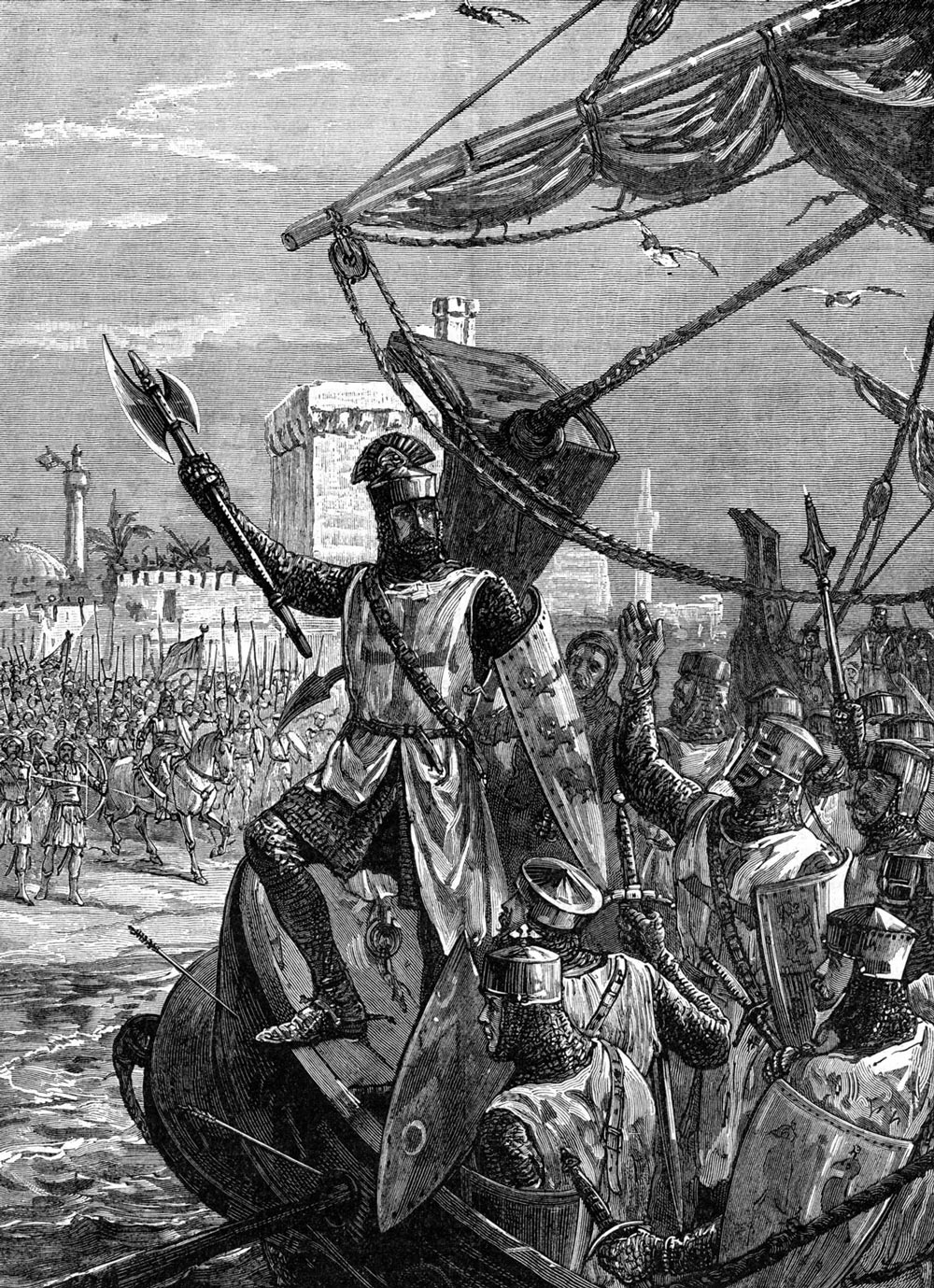

Europe was shocked into action. Philip Augustus and Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Emperor, also took the cross. Richard and Philip’s armies met in July 1190 to depart. Frederick chose to take the land route, but was drowned as he crossed a river on his horse. Richard’s journey was not direct. He wintered in Sicily where he was betrothed to Berengaria of Navarre. On leaving Sicily in April 1191, Richard’s fleet was hit by storms. Arriving in Cyprus he found that its ruler, Isaac Comnenus, had been discourteous to both Berengaria and his sister, Joan, who was one of the few people Richard seems to have shown genuine affection for.

Richard, not a comfortable sailor and fresh from the near-shipwreck of his crossing, took the island ‘almost without reflection’. It was not a long campaign, nor was its success ever in doubt. The crusade now had a useful forward base, and Richard’s reputation was burnished still further. It had already reached the Muslim army.

Once in the Holy Land, Richard was in the thick of the fighting as Acre was besieged and taken. Philip Augustus departed for home soon after, leaving Richard in sole command. He masterminded the army’s summer march down the coast in tight defensive formation, supported by his fleet on the seaward side. He led the army to victory at Arsuf, taking charge of the force that held off a dangerous counterattack until its force was spent. That opened up Jaffa, where he organised the building of a fortress, along with others at Ascalon and on the Egyptian border at captured Daron. When Saladin’s forces launched a surprise attack at Jaffa in July 1192, Richard almost single handedly held them off.

There followed a year of ultimately inconclusive diplomacy with Saladin, through which Richard got to know his brother and chief negotiator, Saphadin, very well. They got on, to the point where Saphadin allowed Richard to knight one of his sons. It was not quite enough to get the crusaders Jerusalem, although the army was twice within sight of its walls, nor for the Muslims to be free of the Christains, who were able to cling onto what was now a much more secure and fortified coastal state. If there was still to be a final battle, perhaps there was more understanding. During the fighting, Richard’s horse was killed underneath him. Saladin spotted this, sending his groom with two horses through the melee of the front line to Richard. It things remained inconclusive, the Christians were allowed to visit Jerusalem to complete their pilgrimage. Richard chose not to go, although he had come so close.

Still the story does not end there. Returning home, Richard was again unlucky with the weather. First his ship had to put in at Corfu, which was held by the Byzantine Emperor who had counted Cyprus as his territory. Continuing with a small group disguised as Templars, Richard was then shipwrecked and had to journey on foot through central Europe. There he was captured by Leopold of Austria, who Richard had offended by casting down his standard from Acre, and handed over the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI. Sadly the story of the troubadour Blondel scouring the castles of Europe for Richard is fiction - Richard was a high profile prisoner, allowed to run at least some of his affairs from a distance while the ransom was raised. Both Philip and his brother John took advantage as best they could. On his release, Philip’s message to John could not have been clearer:

Look to yourself, the Devil is loosed.

King Philip Augustus in a letter to John (1194)

Philip was right. Richard was soon back in the saddle and victorious at Freteval in 1194. By the time that peace was agreed with Philip at Louviers in 1196, Richard had recovered all of his lost possessions. He had lost none of his authority. To make sure of it, fortifications were raised and improved. The greatest of these, Chateau Gaillard in the Vexin, went up over the winter of 1197-98. It was thought to be impregnable. Richard also threw a ring of alliances as far around Philip as he could. While Philip had married Ingebourg of Denmark, a descendant of Cnut with a theoretical claim to the English throne, and threatened invasion, Richard had married Joan to the count of Toulouse, set up money-fief payments to the counts of the low countries and secured the election of his nephew, Otto of Brunswick, as King of the Romans - a stepping stone to Holy Roman Emperor. In the great game of twelfth century Christendom, Richard had a very strong hand against Philip Augustus, himself one of its best players.

Then in 1199 Richard received reports - fake as they turned out - of treasure being withheld from him at Chalus in the Limousin. Besieging the castle, he ventured that little bit too close with not quite enough cover. Standard, perhaps, for Richard but he was still not invulnerable. An arrow hit him in the shoulder. It took ten days of pain for him to die. Eleanor and Berengaria had time to join him as he named John as his successor and pardoned his killer, ordering his men to spare the man’s life. He died on 6 April; he was nearly 42.

Is it any wonder that romances about King Richard were being written within a generation of his death?

During his short life his reputation was fabulous; and time has not greatly disturbed it.

Frank Barlow; The Feudal Kingdom of England (1999)

All of which is the stuff of adventure stories. The summer blockbuster which followed the box set intrigue of Henry’s reign. You would be forgiven for wondering how much is really English history. Yet English history is very much there, and helps shed some light on Richard’s matinee idol image.

As was often the case, one of England’s main roles was to contribute heavily to the bill. On becoming king, estimates of Henry’s treasury on his death range from Roger of Howden's 100,000 marks to the 900,000 marks in the Gesta Ricardi. Either way, that’s a lot. Richard found plenty of use for it. On his accession, he paid a 24,000 mark relief to Philip for his feudal lands in France. Philip received another 10,000 marks from him at Messina to allow Richard to drop his engagement to Philip’s sister, Alice, in favour of Berengaria. In 1193 the pipe roll records show spending on thirty castles at the some time as a further 20,000 marks bought off Philip’s planned invasion. This was before two coronations - before and after the crusade - war with Philip in the later years, the 150,000 marks that truly was a king’s ransom, and the crusade itself, which is spending best thought of in terms of an Apollo programme. Richard spent money like few kings before or since. He burnt through it on a prodigious scale.

The king and his administrators were as creative as the situation demanded. Royal officers were fined - charged for keeping their jobs - and both new and replacement offices were sold rather than given out. Feudal incidents were milked, for example if a tenant-in-chief of the king inherited or married. Geld was levied. In 1198 Richard changed his seal so that charters had to be reconfirmed and he could charge through the nose for that as well. Cyprus and Sicily also had funds wrung out of them as he passed through. Richard joked that he would sell London itself if only he could find the right bidder.

All of this was the stuff of nightmares for the wealthy of England, not to mention those who felt the effects trickle down. Magna Carta, however, was twenty years and some important differences away. At the end of Richard’s reign, the cash was still flowing. No baron of any standing conspired with John during Richard’s absence.

Richard’s main misstep had come early on, when making arrangements for the crusade. With Ranulf Glannvill and Hubert Walter joining the expedition, and both John and Henry’s illegitimate son, Archbishop Geoffrey of York, banished for the duration, alternatives were needed. An initial division of power between Hugh de Puisset, bishop of Durham, in the north and William de Mandeville, earl of Essex, in the south, split by territory given to the absent John in the Midlands, didn’t get off the ground when de Mandeville’s died. Instead, William Longchamp was moved from Normandy to be joint justiciar. He had been chancellor from Richard’s accession and bishop of Ely from December 1189. Quickly, Longchamp was given superiority over Hugh, who was arrested. When Archbishop Baldwin of Canterbury joined the crusade, Longchamp was made papal legate and was now pre-eminent in England’s church and state. He was, it may be said, temperamentally unsuited to the role. ‘A monster with many heads’ according to Gerald of Wales.

The laity found him more than a king, the clergy more than a pope, and both an intolerable tyrant.

William of Newburgh on William Longchamp

John placed himself at the head of the barons, and they marched on a sympathetic London, describing themselves as the ‘community of the realm’. There was widespread agreement as they ensured Longchamp was deposed, although to describe this as English nationalism is too ambitious. Longchamp’s replacement, William of Coutance Archbishop of Rouen, was hardly an English solution to the problem.

He, and then Hubert Walter on his return in 1193, steadied the ship with reasonable ease. When John revelled following Richard’s capture in December 1193, Philip Augustus invaded Richard’s continental lands. Philip made some headway in Normandy. No dent was made in England at all. Likewise Aquitaine, defended actively by Eleanor as she entered her seventieth year.

My brother John is not the man to conquer a country if there is anyone to offer even the feeblest resistance.

Richard I

Much could be achieved in the name of the king if able people approached it in the right way.

And what a name the king had. Richard rubbed shoulders and went toe-to-toe with two of the finest politicians and generals of the age in Philip Augustus and Saladin, and was emerging at worst respectably and at best with signs of triumph. He had fully involved England in its furthest-flung large scale involvement since the days of Rome. It was he who made the three lions of the Angevin Plantagenets synonymous with the English.

Certainly, though, he was far from faultless. While on crusade Hubert Walter was granted an interview with Saladin himself. Hubert asked what Saladin thought of Richard. Saladin’s criticisms were typically perceptive. Richard, he thought, lacked wisdom and moderation.

Observation bears this out. After taking the cross, and even after news of Jerusalem’s fall, Richard was happy to carry on conspiring with Philip Augustus and warring against Henry II. On crusade he upset nearly every baron in Outremer when he backed Guy de Lusignan for the crown of Jerusalem over the hero of Tyre, Conrad de Montferrat. At the same time, Richard had alienated the French contingent, Leopold of Austria and Henry VI. None of which helped his journey home.

Richard could clearly rub people up the wrong way. When he first became duke of Aquitaine, barons complained of his high handedness. Gaston de Bearn thought him conceited and arrogant but, like most others, he soon was won round by Richard’s charm. This was not the merciful chivalry of a Stephen, though. Richard had an edge. He was less careful than his father and more instinctive than Philip. He had the danger you expect from a king.

This shows up on crusade. If Cyprus was conquered almost as an afterthought, what followed was clearly deliberate. The crusaders took nearly three thousand prisoners at Acre, who Conrad ransomed. When that was not immediately forthcoming Richard, mindful of the delays they would cause and the extra mouths to feed, claimed them into his custody and had them executed in view of the Muslim army. It is likely another thousand Christian captives met the same fate in return. Whatever the tactical merits, it was an extravagant use of leverage and goodwill.

And yet an act like this which does so much to alienate a modern audience may have made little difference to contemporaries. Nobody on either side expected a crusade to be pretty, and Saladin knew the risks these prisoners faced. On another day, Saladin was quite ready to negotiate. On another Richard pardoned his own assassin.

As an absentee king wringing good money after bad out of his lands in pursuit of bloodthirsty personal glory, Richard is easy to vilify. ‘Certainly one of the worst rulers that England has ever had’ was Jim Brundage’s view in Richard Lion Heart in 1973. This was not sudden revisionism.

A bad son, a bad husband, a selfish ruler, and a vicious man

William Stubbs

To his own subjects, Richard clearly remained in favour. His glory reflected back on them. To be a king was to be a soldier, to provide security and to lead.

Judged as a politician, administrator and war-lord - in short as a king - he was one of the outstanding rulers of European history.

John Gillingham; Richard the Lionheart (1978)

'When the legend becomes fact, print the legend’ may be an overused quote but in Richard’s case the facts only make sense because of the legend - it held everything together for him. What caused so much trouble in the years to come worked well enough in the 1190s because of Richard himself, what he achieved and how he achieved it. He was worth every penny.

Richard Coeur de Lion was a great man, perhaps too great a man.

Frank Barlow; The Feudal Kingdom of England (1999)

The castle at Chalus was taken soon after Richard died. Its garrison was hanged except for Richard’s killer. Richard asked for him to be spared. He was flayed alive. The future without Richard did not look nearly as bright.

Without an heir - surely an oversight for a king in his forties - Richard named John as his heir on his deathbed. Before leaving on the crusade he had named Arthur of Brittany, but even in 1199 he was still only twelve. That was a risk, but Richard clearly had every intention of coming back alive. Naming John in 1199 was in its own way as much of a risk. His reputation went before him too.

Bibliography

- Gillingham, J. (2002) Richard I. London, Yale University Press

- Richards, D.S. (2010) The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi'l-Ta'rikh. Part 1. London, Routledge

- Barlow, F. (1999) The Feudal Kingdom of England. London, Routledge

- Tyerman, C. (2016) How to Plan a Crusade. London, Penguin

- Meyer, H.E. (2nd edition, 1993) The Crusades. Oxford, Oxford University Press

- Walter Map (late twelfth century) De Nugis Curialis