The great and terrible

Henry II

Born 5 March 1133 | Died 6 July 1189, Chinon, Anjou

Ruled from the Scots borders to the Pyrenees, set the foundations for English Common Law and just possibly could be England’s greatest king. Remembered instead for his temper and the trouble it caused one night.

Henry (by the grace of God), king of the English, duke of the men of Normandy and Aquitaine, and count of the Angevins to all his earls, barons and liegemen, both French and English, greeting.

Opening of a charter of Henry Plantagenet, 19 December 1154 at Westminster

As soon as Henry Plantagenet was old enough, he led a campaign to secure the English crown from King Stephen. Henry was grandson of Henry I; Stephen was a usurper, and not a successful one at that. When Henry ran out of money to pay his troops in 1148 and was bailed out by no less than Stephen himself, gallantly funding the voyage home for Henry and his men, it did not bode well for his future. If that was all you had to go on, what happened next might come as a surprise.

In 1150 he was invested as duke of Normandy - also part of Henry I’s inheritance. The following year he became count of Anjou on the death of his father, Geoffrey. In 1152, Henry married Eleanor of Aquitaine, adding her lands to his. 1153 saw Stephen’s rule in England run its exhausted course as he agreed to a joint monarchy with Henry until his death. When that came in 1154, Henry ruled from Hadrian’s Wall to the Pyrenees with all the prestige, riches and responsibilities that went with it. He was barely into his twenties.

No man dared to do anything other than good, for he was held in great awe

Peterborough Chronicle, 1154

Even the Gesta Stephani - the Deeds of King Stephen - somewhat breathlessly recounted in 1154 that 'It is astonishing how such great good fortune came to him so fast and so suddenly.’ But now Henry had momentum. Brittany and much of Wales fell under his influence. The pope approved Henry’s request to conquer Ireland in 1155, even if it took some hasty action in 1171 to bring unofficial gains by the earl of Pembroke over the previous couple of years into the fold. The town and lands of Toulouse finally succumbed in 1173. The homage of King William the Lion of Scotland was added in 1174 and La Marche purchased in 1177. In 1185 Henry was offered the crown of Jerusalem itself as heir to his other grandfather, Fulk V of Anjou. Henry turned them down.

Listed out like this, it all seems too easy. ‘Good fortune’ can sound effortless. None of these lands was quite like the others. England’s government, at least before the dislocations of Stephen’s reign, had been sophisticated. Some of this had filtered across to Normandy under the king-dukes between 1066 and 1141. Move into the Loire provinces of Anjou, Maine and Touraine and rule became much more personal between Henry and his barons. Head further south still and Aquitaine presented a maze of established, querulous lords, ecclesiastical potentates like the Archbishop of Bordeaux, and powerful towns like Bordeaux and La Rochelle. All of these territories, however, were built around their king, duke or count. Power, justice and direction came from the top. Even in England - as Stephen had unintentionally demonstrated - take away a firm hand and Pandora’s Box could spring open. For this to work, Henry would need to be everywhere at once. It is often said that overnight success comes from twenty years hard work. For Henry, this was slightly different: his overnight success put him in the saddle for the next three and a half decades. Unceasing, right to the end. For all the effort that needed to go in to even stand a chance, could it be done?

The first option was a non-starter. Moving all of his territories onto a single, truly imperial footing would have been the work of several lifetimes, if it could be done at all. To resolve the contradictions of centuries of local custom and law, competing vested interests, and then to find the right kind of administrators would have defeated the best of them. What Henry tried to do still nearly defeated him. He had the insight to treat his lands for what they were - a purely personal accumulation - and to realise that what worked in the Oxfordshire countryside might not stand much chance of success within sight of the Mediterranean.

That meant making the best of it where you could. Here, England was the prime candidate.

By comparison with his other lands, England was centralised and its government was sophisticated. Henry’s grandfather, Henry I, had built on what the Anglo Saxons had achieved, together with what had worked under his father and brother. Much of this had been scattered to the winds under Stephen, as barons had taken their chance to make a grab for local power under cover of the royal family’s civil war. Henry II had to turn the clock back, not just to better, calmer days that would free up some of his time, but to a kingdom that could run much of its own administration in his absence. And absent he was, for more than twenty of his thirty-five years on the throne.

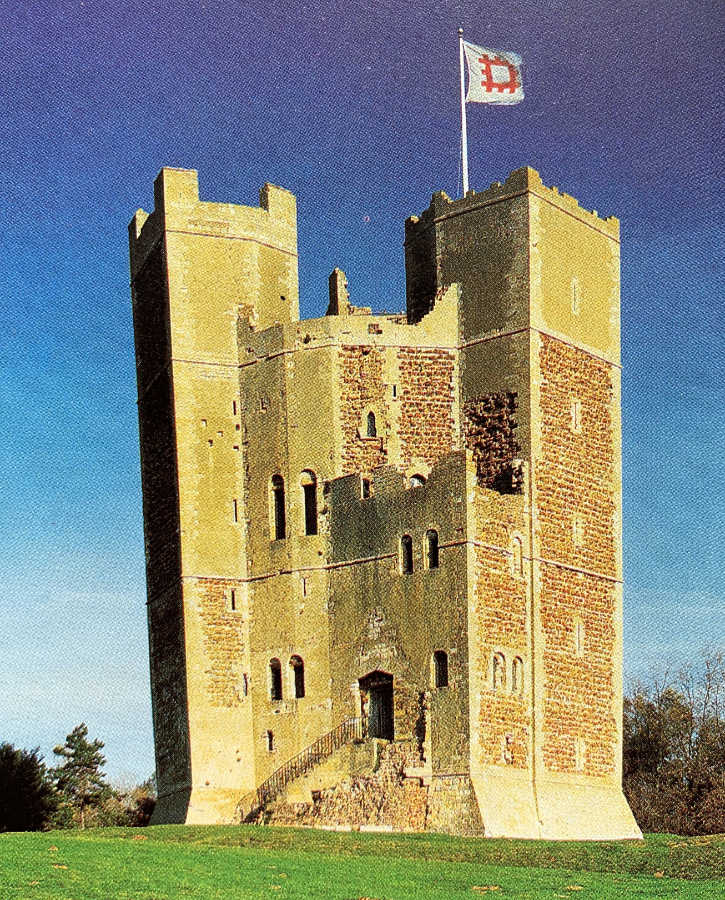

Henry’s Coronation Charter in 1154 hit all the right notes about those good old days. He promised to restore the 'concessions, gifts, liberties and free customs, which King Henry, my grandfather, granted.' It was far from all ‘jam today’ for his barons, though, as Henry also needed to secure his power and revenues too. Hundreds of unlicensed adulterine castles that had sprung up under his predecessor were ordered to be destroyed immediately. Henry was careful that royal rights were rebuilt after the setbacks of Stephen’s reign, but there was a genuine question of what those were.

Henry Plantagenet, schooled to be a king in every particular, was above all else a lawyer, one of the outstanding lawyers, indeed, in English History.

G.W.S. Barrow, Feudal Britain; Hodder & Stourton (London, 1976)

His early visits to England during the 1150s and 1160s saw a series of meetings intended to straighten out at least some of England’s laws. Rights and jurisdiction became the order of the day, supported by a written record rather than a purely personal relationship. Change did not happen overnight, but Henry’s changes lasted a lot longer. While not perfect, Henry’s legal settlement formed the basis of English Common Law that was still recognisable in the nineteenth century. Parts of it are still going strong in the United States today.

This only chipped away at Henry’s problem. He was still in demand in England, and still very much crucial to his other lands if his titles were not to become as ceremonial as those of the king of France, about whom Bertran de Born could observe archly that ‘Five duchies has the French crown and, if you count them up, there are three of them missing’

Henry brought his terrific energy to bear. He was always in the saddle, in the words of Walter Map, who knew Henry directly and speaks like a man who had to keep up, ‘moving in intolerable steps, like a courier… impatient of repose, he did not hesitate to disturb almost half Christendom.’ Barons could easily be forgiven for thinking that Henry could appear over the horizon at any time. That was the key to the illusion - the fear that you were never out of sight, out of mind, or out of reach.

That fear was likely very real. Kings, dukes and counts had typically been wealthier and so more powerful than those beneath them and so on down the social scale. This was usually kept in proportion, though. In a territory the size of Anjou, for example, there was only so much land that could provide extra resources and leverage to the count without the nobility’s approval, or at least equanimity. Aquitaine may have been larger, but in practice the powers of the duke had been weaker. This had given the nobility in a land something of a sporting chance. It was why Harold Godwineson may have given the English aristocracy pause in 1066 at the prospect of him combining his family lands with those of the crown. William the Conqueror, of course, achieved this even more spectacularly and suddenly a few months later to arrive at a tremendous financial and material advantage over both his barons and his neighbours. Henry, with lands and revenues from a huge slice of Christendom, was a quantum leap forward again.

How could a baron - in his mind fighting for his rights - compete with that? Castles offered one option. They were the arm’s race of the day, and because of the great advantage they gave to defenders had become a favourite of local lords on the make. Hundreds of the adulterine castles had sprung up in England during Stephen’s reign. Local protection may have been part of the rationale; holding on to illicit gains was more often the case.

Again, this is where Henry’s talents shone through. He could unlock castles with ease ‘as a man might pluck fruit.’ He had the insight to match his financial muscle and weaponise it. In the words of his twentieth century biographer W L Warren, Henry II’s revolution ‘swung the balance decisively against disorder by harnessing wealth to the defeat of defiance.' While Henry did not seek out pitched battles - sensible leaders avoided these where they could - his huge resources and formidable reputation kept his territories in their place. Without viable options of their own, barons, towns, churchmen and even kings had to like it or live with it.

Success may have run away with Henry. Even if it did not, success on these terms may well win minds but probably would not win hearts.

Henry’s tactics from 1159 to 1164 plunged him deeply into trouble with many people: with the king of France, the Welsh, the Scots, the Bretons, the Poitevins… They were tactics spawned of an overweening, youthful self confidence.

W L Warren; Henry II (Yale University Press, London; 2000)

If a lord could not stand against Henry, who could? Together they were stronger, but what they really needed were princes, a queen, even a king of their own.

Another solution to Henry’s problem was to bring in the family firm. Queen Eleanor had always played an important role in governing Aquitaine and in 1172 was joined by their son, Richard, as duke. Their next son, Geoffrey, was set up as count of Brittany. Here, they could find hands on experience of ruling with at least some of the status and revenues that went with it, even if Henry himself remained in charge. Henry’s idea, it seems, had been for his lands to flow through his family - an 'Angevin commonwealth' - with him at the head.

His eldest surviving son should have completed the set, at least for now. Henry the Young King was crowned as King of England in 1170 - well within his father’s lifetime - and was expected to succeed to the family heartlands of Normandy and Anjou as well. He was a star of the tournament circuit, married to the daughter of the king of France, and promised a glittering future alongside his brothers. As always, there was a ‘but’. Henry II had shared the title but not the power or the revenues of England. Maybe Henry thought his son unprepared; more likely he could not practically give yo the revenues and status of the royal crown. Still in this thirties, Henry II had plenty of ruling left to do.

Frustrations inevitably grew. Henry the Young King had a title with nothing to show for it, made worse when two of his brothers looked to be up and running. When the youngest, his father’s favourite John, was awarded the territory of Chinon in the family heartlands which the Young King had expected for himself, it proved too much. In 1173, encouraged by the king of France, Eleanor, his brothers and a host of barons, Henry the Young King gave Henry II’s lands the rebellion it was waiting for. Seizing their own chance, Henry’s neighbours the count of Boulogne (who was married to Stephen’s daughter), and the counts of Blois and Flanders joined the rebels, as did King William the Lion of Scotland.

Those men who joined the party of his son did so not because they regarded his cause as juster, but because the father was trampling on the necks of the proud and haughty, dismantling or appropriating the casts of the country, and requiring, even compelling, those who occupied royal lands to relinquish them , and be content with their own patrimony.

Ralph of Diss

Only a few barons actively supported Henry II. He had, at that moment, lost it all. He would have done, too, had he not kept his head, his money and some vital support from the English administration. Justiciar Richard de Lucy, Constable Humphrey de Bohun and Ranulf Glannvill stood firm and kept the money flowing. Henry hired mercenaries and concentrated on strategic gains to unpick the rebels rather than flashier, morale-boosting engagements. His strategy was about territory and purpose.

William the Lion was captured at Alnwick, the earl of Norfolk surrendered, and the earl of Leicester soon followed. The French attack on Rouen collapsed and, as 1174 progressed, Henry’s sons and Louis VII steadily ran out of options. Henry II was back in full command of his lands before the end of the year and, by adding the homage of the king of Scotland, had actually increased them. From the North Sea to the borders of Spain, Henry was victorious. It was a staggering achievement.

Not everything changed, however. While Eleanor was placed in captivity for her part, to be wheeled out only for ceremonial occasions, family being what it is Henry’s sons were reconciled with him and retained their titles. Henry the Young King received a more generous financial settlement and went back to jousting, and there was an abortive attempt to establish John in Ireland. Nothing like true loyalty or trust emerged on either side. After Henry the Young King’s death in 1183, Richard was lined up to succeed in England and the heartlands, but there was no coronation.

There was never true affection felt by the father towards his sons, nor by the sons towards their father, nor harmony amongst the brothers themselves.

Gerald of Wales, c1190

Louis VII continued to ferment discord and revolt where he could. His son, Philip II, succeeded to the throne in 1180 and proved far more adept at this. Soon, relations between Henry and his sons worsened still. Gerald tells a colourful story, which nonetheless may capture Henry’s feelings well:

In Winchester Castle there was a gaily painted chamber with one blank space left at the king’s command. In his later years, Henry had the space filled with a design of his own choosing. There was an eagle painted, and four young ones of the eagle perched upon it, one on each wing and a third upon its back tearing at the parent with talons and beaks, and the fourth, no smaller than the others, sitting upon its neck and awaiting the moment to peck out its parent’s eyes.

Gerald of Wales, c1190

To Warren, at a bit more distance, ‘their squabbles loom large in the story of Henry II’s later years because there is little else to tell,’

It was only in his last weeks that Henry II’s tremendous energy finally ran out. Campaigning again against his sons and Philip, it is said that the news that John had gone over to the rebels finally sapped the last of his will. Henry died at Martel in 1189. His illegitimate son, Geoffrey, Chancellor of England and Archbishop of York, stayed loyal to the end.

To him, what really mattered was family politics and he died believing he had failed. But for over thirty years he had succeeded.

John Gillingham, Oxford Popular History of Britain (Oxford; 1993)

To look at contemporary reaction, people agreed. William of Newburgh though ‘the experience of present evils has revived the memory of his good deeds, and the man, who in his own time was hated by almost all men, is declared to have been an excellent and profitable prince.’ And if that sounds like Henry had quickly become part of the good old days himself, then they give away something about the man too.

In physical capacity he was second to none, capable of any activity which another could perform, lacking no courtesy, well read to a degree both seemly and profitable, having a knowledge of all tongues spoken from the coasts of France to the river Jordan, but making use only of French and Latin.

Walter Map (c1190-1193)

Gerald of Wales, who like Walter had seen Henry for himself, paints a picture for us of '…a man of reddish, freckled complexion with a large round head, grey eyes which glowed fiercely and grew bloodshot in anger, a fiery countenance and a harsh, cracked voice. His neck was somewhat thrust forward from his shoulders, his chest was broad and square, his arms strong and powerful. His frame was rather stocky with a pronounced tendency to corpulence, due rather to nature than indulgence, which he tempered by exercise. For in eating and drinking he was moderate and sparing, and in all things frugal in the degree permissible to a prince. To restrain and moderate by exercise the injustice done to him by nature and to mitigate his physical defects by virtue of his mind, he taxed his body with excessive hardships, thus, as it were, fermenting civil war in his own person.’

Gerald also observed that ’He was addicted to the chase beyond measure… he would wear out the whole court with continual standing.’ Even when not in the saddle, Henry was full of energy if not full of patience.

He was a man easy of access… witty, second to none in politeness, whatever thoughts he might conceal within himself…. He was fierce to those who remained untamed, but merciful to the vanquished, harsh to his servants, expansive towards strangers, prodigal in public, thrifty in private. Whom he had once hated he scarcely ever loved, but whom he had once loved he scarcely ever called to mind with hatred.

Gerald of Wales; c1190

If some of this sounds like idealised qualities of a medieval king, that’s exactly what Henry was and he was very good at it. If this were purely an idealised version, we might not get that glimpse of Henry behind the scenes. There is plenty to relate to in this, and to sympathise with as well. Henry’s efforts to ward off an expanding waistline have a modern ring to them. Vanity, perhaps, but also a challenge in a role where conspicuous entertaining was unavoidable. Henry’s expectations of himself adding to the pressures. The signs of this constant activity are also visible. As well as a strong physique, the cracked voice gives us a strong hint of how much he must have been constantly in demand. His lack of sympathy to his court and servants is telling - there is the lack of patience of a man with too much on. A sharp exterior that wards off all but the most essential questions.

Gerald also gives us a diplomatic nod to one of Henry’s other famous characteristics, the ‘Angevin rage’ where his eyes would bulge, veins throbbing in his head as his volcanic temper let loose in a fit of royal ira et malevolentia - his anger and ill-will.

Some of this was no doubt employed strategically. Fear is always a friend of princes, and Henry’s anger was something to behold. When he held your lands, your fortune and quite possibly your life in his hands, it no doubt served to deter many of the less determined. Yet ‘uncontrollable’ is a word often used to describe Henry’s temper, and this could be very dangerous in someone with so much power. His sons showed the same thing, and so it may have been a family trait, if temper can be genetic, but then they simply could have copied Henry’s example. Taking Gerald’s description as a whole, though, there may be a glimmer of understanding behind the tyrant. We know the demands he placed on himself. Tiredness, impatience, exasperation - particularly with those with whom he’d hoped to shared the burden - all of these can shorten a fuse so that the slightest spark lights it.

These things still have consequences. But when we think of them, it is worth reflecting on what is personal - the tantrums of the bully with too much power - and circumstances which, at least after a while, become all too human if not inevitable. Saints don’t always make for good kings.

Right to the end, Henry stayed one step ahead of the rest. He passed near enough all of his territories on to his sons, if only to be overshadowed by the highs and lows of each. But still, he was the leader who won, held, lost and won again an empire that exercised the minds of both England and French kings for centuries to come; he was the lawyer who set the foundations for English law that would last beyond the industrial revolution, and he founded a royal dynasty that would stay on the English throne for over three hundred years. If he was feared more than loved well, that can be good advice for princes as well.

he reigned for 36 years unconquered and unshaken, except by the sorrows inflicted on him by his sons, which, it is said, he bore with a bad grace so he died through their hostility.

Walter Map (c1190-1193)

Tell it this way, and Henry II is England’s forgotten great king. That is partly because, from thirty-five years of unrelenting effort, it is one night that is remembered. It can become a different story once you meet Thomas.

Bibliography

- Clanchy, M.T. (1983) England and its Rulers. London, Fontana

- Warren, W.L. (2000) Henry II. London, Yale

- Strickland, M. (2016) Henry the Young King. London, Yale

- Walter Map (late twelfth century) De Nugis Curialis

- Bartlett, R. (2006) Gerald of Wales: A Voice of the Middle Ages. Stroud, The History Press