'Not one hide of land that he did not know'

Why England was worth conquering

Conquering England and becoming its king gave William prestige. It upheld its honour. Even in the eleventh century, though, prestige and honour only went so far. William bet everything on England in 1066 because the kingdom was rich. England not only farmed and traded on a level to compete with anything Christendom had to offer, but its strong, centralised monarchy and sophisticated administration meant that a king could get his hands on that wealth in cold, hard cash.

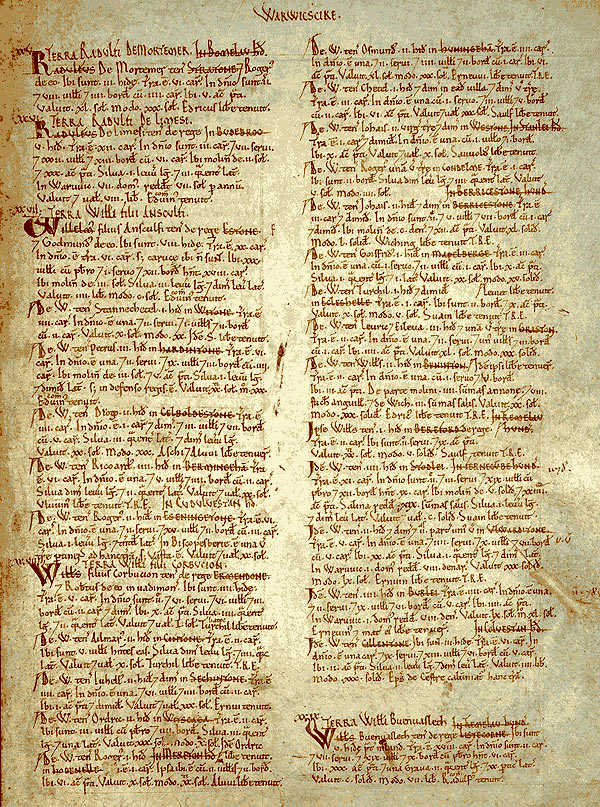

Domesday Book, commissioned in 1086 and completed not long after, shows us this in action. It lets us follow the money. It also gives an amazing view into the workings and thinking of a land beyond the tales of kings and churchmen, battles and conquest. If that is more your thing, don't worry, there is plenty more on the way. Pause to look at what they were fighting for, though, and it suddenly makes a lot more sense.

Fulcran holds of the bishop Butcombe. Alweard held it TRE and it paid geld for three hides. There is land for three ploughs. In demesne is one plough and six slaves; and eleven villains and four borders with five ploughs. There is a mill rendering 20d, and ten acres of meadow and thirty acres of woodland. It was and is worth £4.

From Domesday Book, Somerset, the lands of the Bishop of Coutances

There is a lot packed into one small paragraph, translated from a dense Latin shorthand. There are near enough 13,000 others like it in the Domesday Book.

It tells us that in 1086, when the Domesday survey was carried out, Fulcran was the local lord. He held the land from the bishop of Coutances, a Norman as Fulcran almost certainly was too. That he held the land - but did not own it - is important. The bishop likewise only held the land as a tenant-in-chief of the king, who alone owned the land by right of conquest. These holdings were in return for certain dues - rents, services and taxes - and could be taken away if the tenant came up short.

It is taxes that Domesday is interested in here. Or more precisely, the productive assets that tax could be charged on.

Geld was the main Anglo-Saxon royal tax by the eleventh century, whether to finance the king or ‘Danegeld’ to pay off invaders either as an alternative to conquest or as the result of it. Geld was assessed on hides, which became carucates as you headed north and east. Originally a unit of land, hides were not in fact the same size, and had become a unit of productive capacity - the size of land that could generate a certain amount. This thinking carries on throughout the entry - we are not told that there are three ploughs, but land for three ploughs. Again, the expectation of what land each plough can cover, not the wood and iron assets resting or rusting in a barn.

When a king raised a geld, the rate would be set at a number of pence for each hide (this was old money, so pence is d). So a 2d geld would have meant Fulcran would have to lay his hands on 6d in cash by the time the royal collectors made their rounds. He would have other obligations: to begin with to those who lived on and farmed his land as well as what was owed to the bishop, as well as to finance military service if called upon. Domesday anticipates this - the king is not about to bankrupt taxpayers whose future loyalty and money he relies upon. There is a distinction between the land ‘to the geld’ and what Fulcran has in demesne, the land ‘in lordship’ whose output goes to the lord rather than his tenants. The surplus production, over and above the immediate requirements met by the lord’s ‘inland’, are the first target for the geld. But Domesday does not miss a trick; the value of demesne is tracked as well together with revenue streams - here the dues paid from the mill - and other potentially valuable assets like the woodland with its hunting, forage and timber.

While the focus is on land, people are not forgotten. This is not a census. It cares about those responsible - Fulcran and upwards to the bishop. It also cares about people as productive assets: the slave and the peasants, the bordar at the lower end of the economic scale and the villain, who was still notionally unfree but better off.

Not bad for a handful of words, but that is not all.

Almost as a throwaway line at the start and end, Domesday gives us a clear snapshot of the land as it stood twenty years previously, its lord and its value TRE, which was shorthand for tempore regis Edwardi - the time of King Edward and specifically the day on which he was ‘alive and dead’ at the start of 1066. There is no doubt or speculation in these entires. They are perfectly preserved through the fog and upheaval of conquest, uprising and the rush for lands by the incoming Normans. We will think about what this means shortly.

We also know that this was the summary, the highlights of what the Domesday Survey gathered. Most of Domesday is bound together in a single volume, written up in one man’s handwriting. Next to this we have Exon Domesday, covering the West Country, and Little Domesday. Little Domesday covers Essex and the East Anglian counties and is the penultimate version of the study, made before the final writing up which took place by, as far as we can tell, a single member of the royal chancery in Winchester. It was even more thorough. Looking in on one of Ralph Baynard’s manors in Clavering Hundred in Norfolk gives a good idea of this (the square brackets help expand the shorthand):

In Wheatacre [there was] 1 free man of Harold’s. 2 carucates, where a Frenchman holds. [There have] always [been] 10 villans and 5 bordars. Then [there were] 4 slaves; now 2. [There have] always [been] 2 ploughs in demesne and 2 ploughs belonging to the men. [There is] woodland for 8 pigs. And [there are] 30 acres of meadow. […] This man R[obert] FitzCorbucion claims and he has a livery officer. [There is] pasture for 200 sheep. [There have] always [been] 2 horses. Then [there were] 7 head of cattle. Then [there were] 12 pigs; now 17. Then [there were] 200 sheep; now 100. Then [there were] 6 hives of bees. And [there are] 7 free men in soke to the fold [and] commendation, 18 acres. [There have] always been 2 ploughs. And [there is] 1 acre of meadow. Then it was worth 30s[hillings]; now 45s. The whole [was] in exchange.

From Domesday Book, Norfolk, lands of Ralph Baynard

Less crisp, but with an unmistakably official tone it give us more. Much more. There are pigs, but also notional land for pigs which could be had if Ralph is running the manor efficiently, we presume. The king, it seems, does not want to be short changed by bad management. The picture of 1066 (‘then’) is clearer too, although we can only wonder what happened to the bees.

To all intents and purposes, all this detail from across the kingdom was collected in about a year.

This was a huge effort. Why? And why the rush?

William decided on the Domesday survey at his Christmas court at Gloucester in 1085. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

After this the king had great thought and very deep conversation with his council about this land, how it was occupied, or with which men. Then he sent his men all over England into every shire and had them ascertain how many hundreds of hides there were in the shire, or what land and livestock the king himself had in the land, or what dues he ought to have in twelve months from the shire. Also he had it recorded how much land his archbishops had, and his diocesan bishops, and his abbots and his earls, and - though I tell it at too great length - what or how much each man had who was occupying land here in England, in land and in livestock, and how much money it was worth. He had it investigated so very narrowly that there was not even one single hide, not one yard of land, nor even (it is shameful to tell - but it seemed no shame to him to do it) one ox, not one cow, not one pig was left out, that was not set down in his record.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 1085

There were clearly many layers in this great thought. It is likely that they boiled down to money and loyalty, as is often the case.

In 1085 "men declared, and said for a fact, that Cnut king of Denmark, son of Swein, set out in this direction, and wanted to win this land with the support of earl Robert of Flanders, because Cnut had married Robert’s daughter." Again, the Danish claim from 1066 and before hung over William. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle’s account continues with how William hurried back from Normandy, hiring mercenaries from France and Brittany, and ravaging the land up the English east coast so that an army landing there could not support itself.

William’s usual decisiveness and ferocity were on show again. The mercenaries stand out as unusual, though. William had Bretons in his army in 1066, but they were alongside Normans. William had also raised the fyrd - the Anglo-Saxon army - more than once. There is no mention of either here. It is hard not to suspect that William, never trusting, had loyalty problems. His son, Robert Curthose, was often in rebellion in Normandy by this stage, and William had to imprison his half-brother Odo, bishop of Bayeux.

[In 1086, William called] all the men occupying land who were of any account all over England, whichever man’s men they were [to Salisbury and on the plain] all submitted to him, and swore loyal oaths that they would be loyal to him against all other men.

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 1085

William clearly did not want local ties between the leading barons to undermine his leadership of the knights and lessor lords who held their land from someone other than the king. This was not a threat of an English uprising, it was a Norman risk that enough of the newcomers could find an alternative king a better bet than William himself.

The Domesday survey not only gave William sight over who had won the race for land after the Conquest and the Harrying of the North, it was also the opportunity for the king to approve these landholdings, tacitly or otherwise. There was a trade off - lords had their lands and gains legitimised in return for the loyalty to the king, and to King William specifically.

Once again William was relying on an oath, and one which again may well have been taken under some duress. Knights or nobles not part of the Salisbury Oath might not have expected to be prosperous knights or nobles for much longer.

In the meantime, William’s mercenary army needed money. This meant a tax and most likely a heavy one. The Chronicle’s emphasis on the landholding of the major churchmen may reflect the interests of a churchman author, but at a time when the Church was trying to assert some independence from secular power and their taxes, William most likely wanted very clear lines drawn around their claims. There had already been disputes. At the Trial of Pinnenden Heath Odo and Lanfranc, archbishop of Canterbury, fought publicly over lands in the 1070s. Now the spotlight shone on all.

This was a huge amount of detail, apparently from a standing start. How did William and his administrators do it? The answer may have been there all along.

The last part of the picture is how William achieved it. Under threat of invasion and unrest in Normandy, most of the information was compiled in probably not much more than a year. Around 13,000 places, following a time of upheaval and changes in landholding with the disputes that come with it, down to what may well have been the last sheep, pig and cow.

It was an Anglo-Saxon solution to William’s Norman and Danish problems.

Anglo-Saxon England was a rarity in Europe at the time. It had one system of local courts and one coinage, together with the established direct tax of the geld. It also had the royal writing office, which is something of an understatement for the team of people who could make the mechanics of royal government, its writs and geld, work. For all the change put in motion by the Conquest, all this had survived.

There are records which survive showing the same kind of survey earlier in William’s reign for individual counties such as Northamptonshire and Somerset. Hemming’s Cartulary and the Crowland Chronicle both refer to "rolls kept in Winchester" which are now lost. The main clue is in Domesday itself, as the consistent detailed references to the last Anglo-Saxon landholders from the time of king Edward - TRE - and the value of their lands suggests that those records must have been available either centrally or in the shire and hundred courts. It is hardly convincing that it could be remembered or recreated with that kind of clarity after the destruction of the English nobility that Domesday itself records, the upheavals of the Harrying of the North and the simple passing of time.

There is an intriguing thought, although no more than that, of when the last Anglo-Saxon survey might have taken place. The intention of the shorthand 'TRE' is specific to the day, 5 January 1066. Landholding changed with some frequency, especially when seizure of estates was the usual result of a loss of royal favour or a more lenient punishment for backing the wrong horse in a rebellion like that of Harold Godwinson's brother, Tostig, in 1065. The Normans never credited Harold as king and were not about to start now, but if the old survey was comfortably in the reign of Edward, why not just say so? As it is, the information is pulled into the last moment of his reign. This may simply be accurate. Or it may just be that all this information comes from later on in 1066, which would be an incredible achievement given the uncertainties and upheaval of that year. Either way, the man with his hand on the tiller of royal government by then was not Edward but Harold. Could a substantial chunk of the information in what is seen as one of the Normans' greatest achievements be taken directly from the government of the oath-breaking usurper Harold? After twenty years still the ghost at their party. Maybe.

The scale of the exercise is what makes it so impressive. After the Salisbury Oath, tenants-in-chief, those who held their lands directly from the king, supplied written details via the network of county sheriffs. Teams of commissioners were dispatched around what look to be seven circuits, covering the country south of the rivers Ribble and Tees. Royal government literally went from place to place, holding sworn inquests at shire meetings to review and test the information and hear any disputes.

The results were then drafted by shire in the type of full detail we see in Little Domesday. There may even have been two drafts at this stage, before the information went to the writing office at Winchester to be compiled into the final version by a single scribe.

And it all happened quickly. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that William had 'all the records were brought to him afterwards'. That may not have been the final version, as there is only so fast one man can write and it seems the eastern shires of Little Domesday may have been more complex and so lagged behind, but even an earlier version would have had less than two years of William's remaining life to be presented to him. That the king had something by the end of 1086 was highly likely.

all the records were brought to him afterwards

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 1086

It is worth remembering that the Domesday Book covers 13,000 places.

This kind of system which is so invasive and thorough does not appear out of nothing and put a decent set of results on the table in about a year. Novelty - especially the kind of novelty that leads to taxation - is opposed, resisted, obstructed and its findings challenged. There is no sign of much more than token grumbling accompanying the Domesday survey. True, William's reputation by this stage was formidable, but he was facing rebellion from his son, Robert, in Normandy and the prospect of Danish invasion. Yes, there was the trade off between recognition of newly won lands in return for the information and held that was to follow, but a safe and stable crown would have had far less need for the survey in the first place. The answer has to be that, fundamentally, Domesday was not new.

There are familiar outriders. The Northamptonshire Geld Roll dates from the 1070s and follows broadly the same format, as does a geld roll covering Somerset from around the same time. Both Hemming's Cartulary in Worcester and the Crowland Chronicle refer to 'rolls kept at Winchester' which are now lost. The tradition of geld rolls continues to the Pipe Roll of 1130 under William's son, Henry. The clear inference is that this was another link in a chain of information than ran back, possibly through the eleventh century and maybe even to the time of King Aethelred and his wars against the Danes Swein and Cnut. Before even that, the tenth century offers us the Burghal Hideage. No more than a summary and based on key towns, the information it provides remains familiar. Domesday stands out because it is compiled (mostly) into a single volume and that, being among the last of its kind, it has stood the test of time as the definitive work.

It's Norman masters may have put a new, feudal, twist on the structure, focusing on people - landholders - rather than the estates and manors, but the machinery that delivered it so quickly, effectively and apparently accurately was very much Anglo-Saxon. England was so sought after by invaders in the late tenth and eleventh centuries not just because it was rich but because it could get at its wealth. English kings had the levers to make this happen so why would their replacements, Danish or Norman, do anything to break Europe's most valuable machine?

Domesday Book leaves us a level of detail about the eleventh century kingdom that is unrivalled and unequalled in Europe for at least a century. It marked the end of the Conquest and the start of a slightly more stable Norman rule. It was the jewel in the the new Norman crown, but in doing so it was the last big hurrah for Anglo-Saxon England.

Bibliography

- ed Williams, A and Martin, G (2002) Domesday Book. London, Penguin Books

- Campbell, J (2000) The Anglo-Saxon State. London, Hambledon

- Wormald, P (1999) The Making of English Law. Oxford, Blackwell

- Chibnall M (new edition, 2009) Anglo-Norman England 1066-1166. New York, John Wiley & Sons