End of the line

When too many rights go wrong

Harold Godwineson is one of the best known names of English history. Harold or Harold Godwineson. Sometimes Earl Harold. Hardly ever King Harold. But king he was. The last king of Anglo-Saxon England.

And there’s the rub. History is written by the winners and, whether it was an arrow or a Norman sword that did the fatal damage, Harold’s army was finally overrun in the fading autumn light of Hastings. Harold had lost.

Harold’s legacy was one of Duke William’s spoils from the battle. Harold the perjurer and usurper would be his fate. Forever Earl Harold Godwineson, demoted and tied through a surname - as much a nickname - to an even greater parvenu, his father Earl Godwine, who rose from obscurity to the peak of the English aristocracy.

William of Poitiers, who was close to the Norman court and writing not long after the Conquest, captures it neatly when looking back at the start of 1066:

After this came the unwelcome report that the land of England had lost its king, and that Harold had been crowned in his stead. This insensate Englishman did not wait for the public choice, but by breaking his oath and with the support of a few ill-disposed partisans, he seized the throne of the best of kings on the very day of his funeral, and when all the people were bewailing their loss.

William of Poitiers

This is as much as might be expected from Normans with a pressing need to justify an invasion and conquest to their new subjects, interested observers throughout Christendom, and possibly even themselves. But who really was King Harold? Did the Normans have a point?

On William of Poitiers’ first charge - was Harold an oath breaker - the answer is yes.

In 1064 Harold sailed to the Continent. In the Norman telling, this was on Edward’s instruction to confirm to William of Normandy that the Duke would succeed to the English crown on Edward’s death. Blown by strong winds, possibly shipwrecked, Harold came ashore at Ponthieu, was captured and then taken to William. Harold then spent time at the duke’s court and out on campaign with him. He fought with William’s army, making a name for himself there with his skill and personal bravery, even pulling some Norman knights out of quicksand on a campaign against Duke Conan of Brittany. Before Harold left, William presented him with arms, as a lord would do in Norman eyes, and swore an oath on not one but two sets of relics. Presumably this was to support William’s succession.

This, of course, Harold did not do. When Edward died less than two years later, Harold was immediately crowned king. His coronation service followed the funeral in Edward’s newly completed Westminster Abbey, the day after Edward died.

Things are never that simple.

Edward the Confessor, son of Kind Aethelred the Unready and his wife Emma of Normandy, spent the 1030s in exile in Normandy while Cnut’s two sons reigned in England. Edward may well have promised William that, should Edward get the crown, William would be his heir. This is easily believable, as Edward was childless, William was his cousin and it is very easy to promise something that you don’t have. Edward’s prospects were limited too, as it took the sudden death of Harthacnut in 1042 to open the door for a return.

Edward, it seems, could be free with promises of the succession. Swein Estrithson, Cnut’s nephew, was also given reason to believe he was next in line for the throne in the 1040s. Writing his Deeds of the Dukes of Normandy around 1070, William of Jumiege claims that Edward sent the then Archbishop of Canterbury to Normandy during the upheavals in England of 1051 to offer the succession to William, who promptly visited England with a large retinue.

As we will see, though, as the years passed Edward entrusted more of the running of the kingdom to Harold, whose titles in royal documents grow from earl to dux to subregulus or ‘under king’. This makes the events of 1064 even less explicable.

It may be that Edward was indeed consistent and wanted things confirmed. This is the Norman view and is implied, if not completely confirmed, by the Bayeux Tapestry. What is missing is the English perspective. None of the three versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle running at the time has an entry for 1064, nor does the compilation credited to ‘Florence of Worcester’. It is the only year that is a complete blank, which can’t help but suggest either editing or that a veil needed to be drawn at some point. Unless the nuns of Wilton count, sewing the Bayeux Tapestry for their Norman patron, we have to wait until Eadmer, writing in the south east in the 1120s, for an English view. He suggests that Harold’s aim was the freedom of his brother and nephew who had been handed over to William as hostages, presumably on William’s visit in 1051. In this telling, Edward counselled Harold against going and was unimpressed on his return - something that can also be read into the Tapestry’s version.

When all this had been done, Harold took his nephew and returned home. There, when, on being questioned by the king, he told him what had happened and what he had done, the king exclaimed 'Did I not tell you I know William and that your going might bring untold calamity on the kingdom?'

Eadmer

Some doubt can be cast on Eadmer’s version. By the time he was writing, William’s son Henry I was king and had married into the family of the Wessex kings. Placing the emphasis on Harold’s folly not Edward's muddling may have fitted a wider narrative. But the Bayeux Tapestry, completed while some of the actors were still alive and so presumably not too far fetched, gives a stronger suggestion that this kind of support for William was not part of the plan.

The Duke’s commanding, even insisting, presence in the scene where Harold is swearing his oath is clear. Harold, if he wanted to go home, may have had no choice and rightly assumed that an oath under duress was no oath at all.

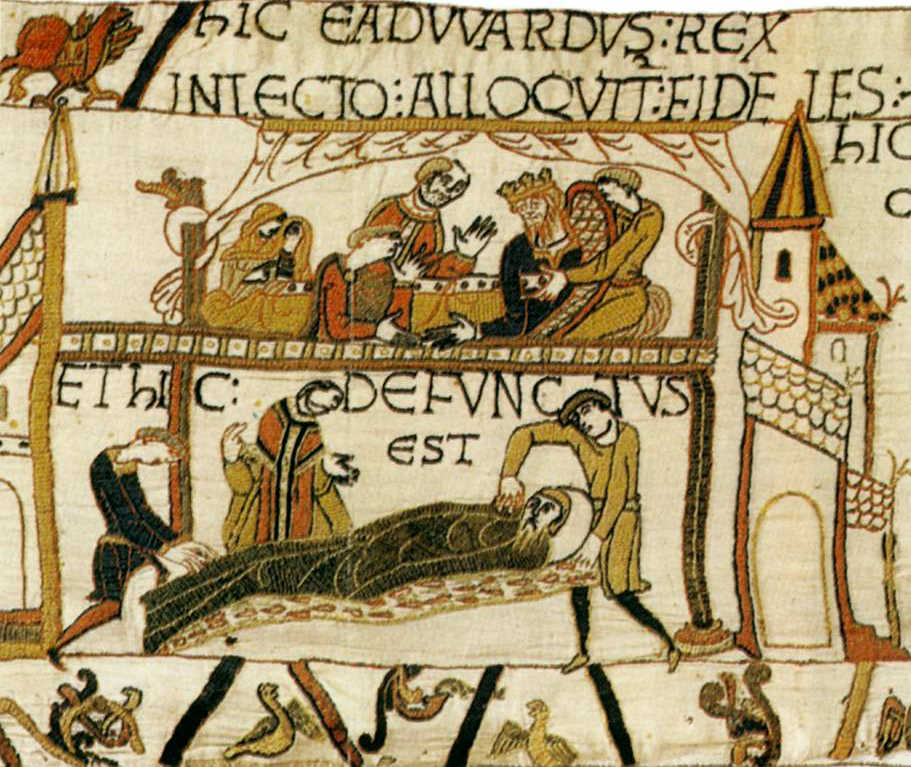

Yet even this was to be overshadowed before long. On his deathbed, Edward nominated Harold as king. The Bayeux Tapestry shows it, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives us detail, and even William of Poitiers concedes it. He puts words into the mouth of Harold’s messenger, coming to Duke William on his landing in England.

[Harold] recalls that at first King Edward appointed you as his heir to the kingdom of England, and he remembers that he was himself sent by the king to Normandy to give you an assurance of the succession. But he also knows that the same king, his lord, acting within his rights, bestowed on him the kingdom of England when dying. Moreover, ever since the time when blessed Augustine came to these shores it has been the unbroken custom of the English to treat death-bed bequests as inviolable.

William of Poitiers

At which point William’s arguments move to his ability to rule effectively and the judgment of God, succinctly expressed in battle. William and the Norman writers had done their best but it is ultimately Edward, not Harold, who unravels their case. For their version to keep its credibility it needs to stand up and if every Anglo-Saxon, and quite possibly many Normans, knew the strength of Edward’s deathbed wishes then there was no hiding it. All they were left was the chance to throw some mud and hope that some of it stuck.

But what of the English? Could it be that for Harold to achieve greatness they would find him thrust upon them?

Bibliography

- ed. Swanton, Michael (2000) The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. London, Phoenix Press