The price of purity

Anne Hutchinson

Born c.1591, Lincolnshire, England | Died 1643, New Amsterdam, America

Midwife, Puritan heretic

Therefore take heed what you go about to do unto me, for you have no power over my body, neither can you do me any harm, for I am in the hands of the eternal Jehovah, my Savior… Therefore, take heed how you proceed against me, for I know that for this you go about to do me, God will ruin you and your posterity, and this whole state.

Anne Hutchinson

The journey from the small Lincolnshire town of Alford to the market port of Boston took some six hours there and back on horseback, when weather and roads allowed. But when John Cotton spoke from the pulpit at St Botolph's, Anne Hutchinson was there to listen. At 27 Cotton was already one of England's leading Puritan preachers, and his doctrine of 'absolute grace', his wonderous descriptions of those transcendent moments when mortal souls were filled with the essence of the Almighty, stirred Anne like none of the more local ministers the Anglican Church had to offer. She and her husband William would travel this road many times over the two decades Cotton was to preach in Boston, from 1612 until he was forced to flee rather than face trial for his nonconformity. John Cotton was well connected with Puritan emigrants, and in summer 1633 he and his new wife set sail for the more hospitable theological climate of Boston's recently-established namesake in the New World, trading the grandeur and prestige of St Botolph's for a small and windowless meeting house in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. And where John Cotton went, so too did Anne Hutchinson, but this resolve to follow her guiding light even across the Atlantic is not why we know about her. Anne Hutchinson's story really begins when she stopped following, when there was no further John Cotton could lead her.

Sometimes it's hard to be a woman. The seventeenth century was one of those times, but that's not the whole story either. Things surely went the worse for Anne Hutchinson because she was a woman, but had she been a man they might not have gone any better.

Puritan women were expected to submit to their husbands, and a wife could neither own property nor conduct any kind of business in her own name, nor could she vote in the General Court of Massachusetts, but they had this in common with every other married woman in seventeenth-century English society. They could not work, and yet they did little else, labouring at their vegetable gardens, caring for their husbands and birthing and raising children at an alarming rate (Hutchinson had fifteen children, all but one before her emigration to Massachusetts, losing one in infancy and two at young ages to the plague). As the first words of their Bible proclaimed, and the story of the very first woman attested, Puritans viewed women as morally weak, as inherently vulnerable to temptation as they were designed to tempt. In common with those of savages and blacks, if not to the same degree, womens' souls were ill-made for salvation, requiring more guidance, more control: the radical social and theological freedoms Puritan men managed to wrest for themselves had not left them inclined to share. Man was to his wife as God was to man. So it was written.

…that the husband should obey his wife, and not the wife the husband, that is a false principle. For God hath put another law upon women: wives, be subject to your husbands in all things.

John Cotton

And yet women were a cornerstone, if not the foundation, of Puritanism. In numbers alone they made up the majority of communicants for all New England churches for which records remain by 1660, and women had long been vociferous supporters of Puritan ministers in England as they were in America. How do we explain this appeal if, as historian Lyle Koehler suggests, the need to define all women as weak and dependent was … deeply embedded in the character of American Puritanism

?

Theologically women were second-class citizens, nothing new there, but emotionally and socially Puritanism perhaps had more to offer. The marriage metaphor, that the elect were as 'brides' to Christ, went deeper than lip service to encompass a genuine sense of blissful submission: as John Winthrop wrote, my soule has as familiar and sensible society with him as wife could have with the kindest husbande; I desired no other happiness but to be embraced of him

. Puritans believed in love matches rather than arranged marriages, and surviving letters contain ample evidence of heartfelt declarations of emotional and physical intimacy – on the Arbella Winthrop described the union between man and wife as being the closest thing on earth to heaven

. Wives' submission was based upon consent, and a husband's authority upon freely-given acquiesence. Men needed the support and devotion of their wives, especially as the focus of spiritual life moved from the church to the home, which became the centre for reading, learning, and preaching the word of God in a manner wholely unlike that of traditional Anglicanism, investing wives with an unprecedented significance.

In the late summer of 1634 Anne Hutchinson arrived in Massachusetts, with her husband William and ten children. John Cotton himself was there to greet them on the pier in Boston. The sale of their English interests had left them wealthy, and they soon acquired a half acre lot on the Shawmut Peninsula (the heart of the emerging city), an island in the bay, and 600 acres to the south. They built a grandiose two-storey timber-framed house opposite that of John Winthrop, and as William threw himself into the cloth trade and became a deputy to the General Court, Anne devoted herself to the needy of the community, becoming an active midwife and spiritual counsellor. They became active members of the First Church of Boston, Cotton's congregation, and Winthrop noted with approval that her ordinary talke was about the things of the Kingdome of God,

and her usuall conversation was in the way of righteousness and kindnesse

.

We must uphold a familiar commerce together in all meekness, gentleness, patience, and liberality. We must delight in each other, make others’ conditions our own, rejoice together, mourn together, labor and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, our community as members of the same body.

John Winthrop

The Massachusetts Bay Colony had been founded in large part to provide a home for those who could find none within the Anglican Church, to build a new community of the Godly, a purified church for the reinvention of faith and worship. They were one body, as John Winthrop constantly maintained, standing against the threats and isolation of embryonic New England, and one spirit against the compromises and corruptions of the Old World. But these very communities were composed of self-selecting dissenters and nonconformists, believers ready to throw off every rule and restraint that came between them and their God, to whom individual salvation was everything. Anne Hutchinson's cards had already been marked for asking awkward questions of the Reverand Zechariah Symmes before she had even arrived in America, aboard The Griffin, and she was closely questioned by Boston minister John Wilson and John Cotton before being admitted to the First Church.

Cotton's ministry was flourishing, and as church membership grew, Anne Hutchinson began holding meetings in her house for women who wished to discuss Cotton's sermons, meetings which in time came to attract men as well (inlcuding the then-Governor of the Massachusetts Colony, Henry Vane), until upwards of 60 people were attending each week. At was at these assemblies that Anne began to share her own intuitions, as well as her growing dissatisfaction with the preaching of John Wilson and various other ministers, with the exception of Cotton and her brother-in-law John Wheelwright (married to William's sister, Anne).

The bone of contention, the faultline which already divided Cotton from most of his ministerial colleagues, was that of the role of traditional morality, of good works in the conversion experience. John Cotton and other adherents of 'free grace' believed that a Christian's spirituality had nothing to do with their outward behaviour, that doing good deeds and following laws were not signs of faith, and that that they might even be evidence against it (in that man-made laws and conventions were a scaffold, a poor substitute for the internal compass and assurance of those who lived in God's grace). The idea was linked to the Calvinist notion of predestination, that God, in his omniscience, knew who would be saved and who would be damned from the very start, before the world was even created, and that nothing individuals did had any power to change that. This Covenant of Free Grace was also called Antinomianism by critics, which literally meant being against or opposed to the law

, placing the adherent outside of any social orthodoxy or contract, described as a seventeenth-century nihilism

in George McKenna's Puritan Origins of American Patriotism.

For the law of the Spirit of life in Christ Jesus hath made me free from the law of sin and death.

Romans 8:2

This rupture came to a head when Free Grace adherents, the majority of the Boston First Church, tried to have John Wilson removed from his position in favour of John Wheelwright. Anne Hutchinson wielded a great deal of influence within the congregation, where she and her supporters frequently got up and ostentatiously walked out of the church whenever Wilson rose to preach or lead them in prayer. John Winthrop, a friend of Wilson, managed to frustrate this effort, but Wheelwright would not be brought to compromise: in a fasting day speech intended to help soothe tensions in January 1637 he instead accused his opponents of being antichrists, a crusade the Hutchinson faction adopted with enthusiasm.

The controversy moved to the General Court in March, where Wheelwright was found guilty of contempt and sedition, a verdict protested by the First Church. An election preceded the new session in May, held in the more orthodox environs of Newtown some eight miles upriver from Boston, and the more conservative votes from outside the metropolis saw John Winthrop replace Vane as Governor. A church synod failed to bridge the theological divide: as Winthrop wrote, two so opposite parties could not contain in the same body, without apparent hazard of ruin to the whole

. Wheelwright was banished in November 1637 and his supporters on the Council likewise exiled or disenfranchised, whereupon the Court turned its attentions to the figurehead within the Boston First Church, Anne Hutchinson, whom Winthrop was to descibe as the grounds of all these tumults and troubles … the root of all the mischief

.

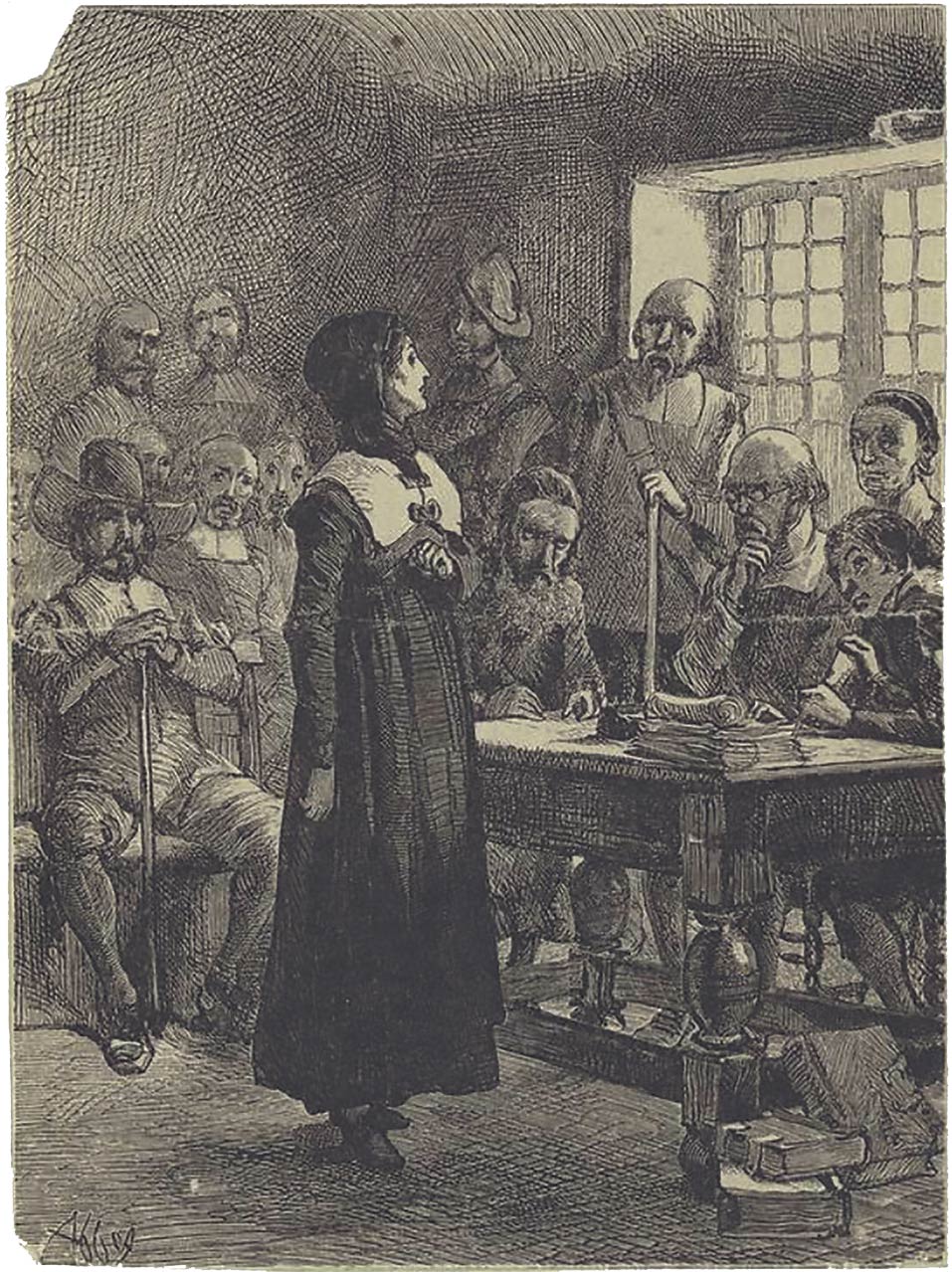

Anne Hutchinson had never been part of the political conflict, nor made any public statements of support, so the Court could only charge her with 'countenancing' those that did, and with promoting troublesome opinions at the meetings in her house. John Winthrop acted, with admirable efficiency, as both prosecutor and judge at the trial, held in Newtown, but Anne Hutchinson proved adept in defending her position, citing Scripture as readily as any of the massed ranks of magistrates arrayed against her. John Cotton was called upon to testify as to what he knew and had heard, but endeavoured to put the mildest possible interpretation on every accusation. Two days worth of proceedings were inconclusive at best, but then Anne Hutchinson delivered herself into the Court's hands when she asked their permission to give you the ground of what I know to be true

. I fear none but the great Jehovah, which hath foretold me of these things

, she continued, before predicting the ruin of the court and indeed the entire colony. In one dramatic and impassioned speech Anne Hutchinson gave Winthrop and the Court everything for which they had been searching, dismissing their power and claiming direct personal revelation from the Almighty as well as threatening divine retribution. This was contempt of court and sedition, plain-spoken, and Winthrop quickly moved for a vote of banishment upon a heretic and instrument of the Devil, upon a woman not fit for our society

.

And so your opinions fret like a gangrene and spread like a leprosy, and infect far and near, and will eat out the bowels of religion and hath so infected the churches that God knows when they will be cured.

John Cotton

Four months detention and a further Church trial followed, in which various ministers including John Cotton tried to wrest from Anne Hutchinson some acknowedgement of and repentence for her errors. To her accusers, Hutchinson was the wellspring of the wickedness and malaise that had afflicted the colony, and they took this opportunity to lay a range of social ills upon her: as Cotton gravely assured her, You cannot Evade the Argument... that filthie Sinne of the Communitie of Woemen; and all promiscuous and filthie cominge togeather of men and Woemen without Distinction or Relation of Mariage, will necessarily follow. Though I have not herd, nayther do I thinke you have bine unfaythfull to your Husband in his Marriage Covenant, yet that will follow upon it.

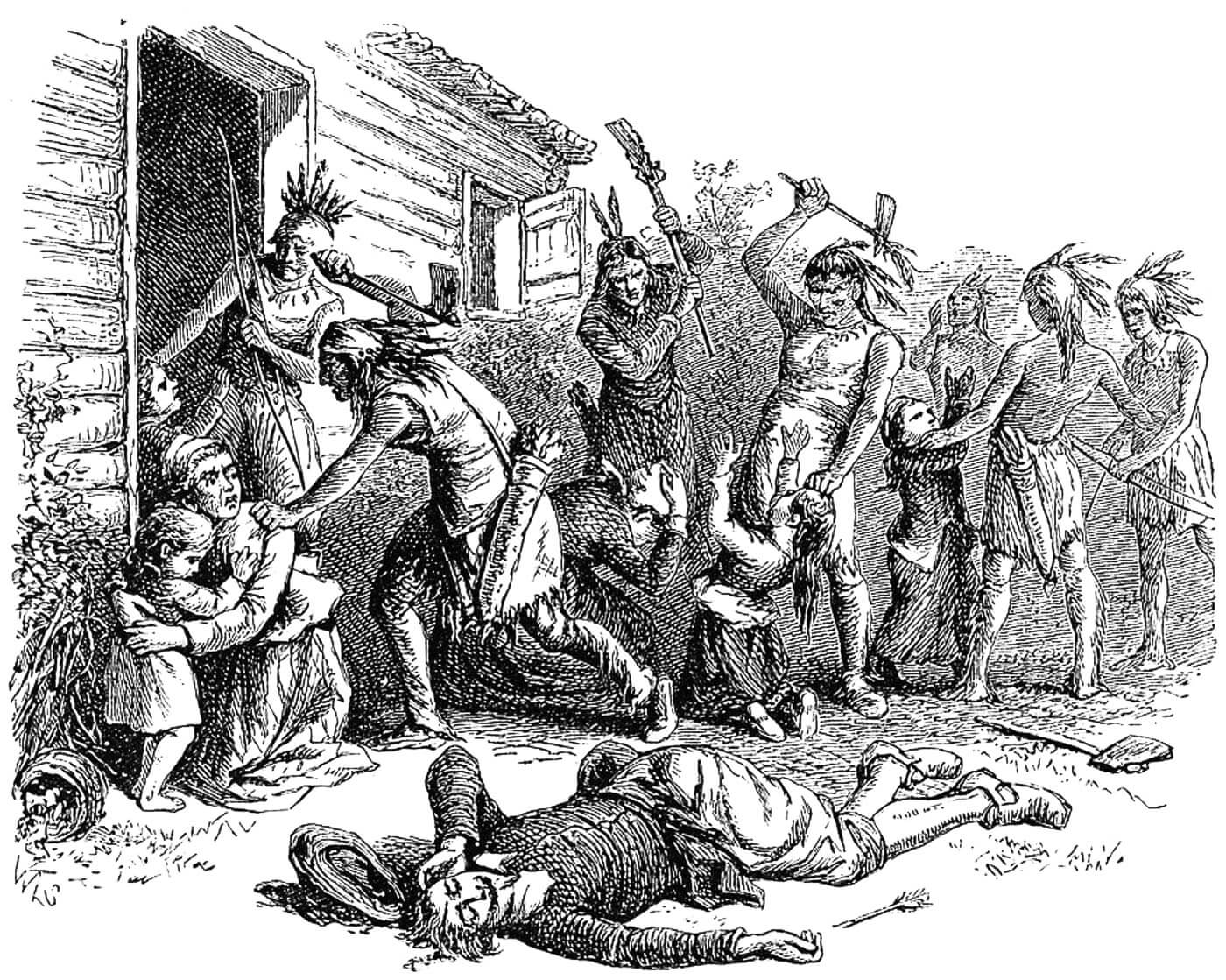

With this elaboration of her potential evils on top of her actual crimes, banishment was confirmed, of Anne Hitchinson, her children, and a number of other Boston congregants who chose to follow her into exile. They trekked for six days through the snow to Roger Williams's breakaway Providence settlement, where William Hutchinson had already prepared a new life for them. The expansion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony soon threatened this refuge, and in 1642 Anne Hutchinson moved still further beyond their reach into Dutch territory, and she and seven of her children (William Hutchinson died in 1641) built a home at Split Rock, north of New Amsterdam. It was here they fell victim to escalating conflict between Dutch settlers and the Siwanoy tribe, as a band of warriors burned down their home and slaughtered almost everyone they found (the nine-year old Susanna Hutchinson was taken hostage and lived with the tribe for somewhere between two and six years before being ransomed back to surviving family members). Massachusetts authorities revelled in this evidence of the just vengeance of God

, a fitting end to the thorn in their side that historian Michael Winship judged to be the most famous, or infamous, English woman in colonial American history

.

The Siwanoy seized and scalped Francis Hutchinson, William Collins, several servants, the two Annes (mother and daughter), and the younger children — William, Katherine, Mary, and Zuriel. As the story was later recounted in Boston, one of the Hutchinsons' daughters, 'seeking to escape,' was caught 'as she was getting over a hedge, and they drew her back again by the hair of the head to the stump of a tree, and there cut off her head with a hatchet'.

Eve LaPlante

On the 425th anniversary of her birth, the Boston Globe described Anne Hutchinson as a Puritan religious leader widely regarded as a symbol of feminism, freedom of speech, and thought

. Her statue stands outside the Massachusetts State House (an honour accorded to neither John Winthrop nor Cotton), but it took law-makers several weeks in 1922 to agree it was 'appropriate'. One of the founders of the Anne Hutchinson Foundation, on the occasion of that 425th anniversary, affirmed the importance of celebrating role models from our past that are women of character, women of courage, women of strengths – even when they're wrong

.

We cannot know who Anne Hutchinson was, nor why she said what she said and acted as she did. We know her from court transcripts, the testimony of aggrieved ministers, and the condemnation of John Winthrop's journals. One of her biographers, Eve LaPlante, a direct descendent who confesses to having been terrified as a child of Hutchinson's reputation as a witch, concludes that Like many figures in history, she is a vessel for our imaginations. She becomes who we want her to be.

Anne Hutchinson has been defined by her enemies, those who tried, convicted, and banished her. That she stood up against those who denied women rights has made her an early champion of feminism. That she was persecuted by those who oppressed other faiths has cast her as a standard-bearer for religious toleration. And that she was the victim of an autocratic regime acting on shaky legal grounds has been enough to enshrine her as a defender of personal liberty and civil rights. She was out of step with, and actively opposed, the prevailing values of her time, values we no longer share, which has made it all too easy for us to see her as somehow ahead of that time, and, if we are careless, even 'right', or 'one of us'.

We tell ourselves stories in order to live… We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Joan Didion

The Puritans weren't perfect. The legislator,

wrote Alexis de Tocqueville some two centuries later, entirely forgetting the great principles of religious toleration which he had himself demanded in Europe, makes attendance on divine service compulsory, and goes so far as to visit with severe punishment, and even with death, Christians who choose to worship God according to a ritual differing from his own.

John Cotton put it more plainly: toleration was liberty… to tell lies in the name of the Lord

.

The Puritans were very much of their time, and in that time they were strangers in a strange land, surrounded by the Godless wilderness in which they had chosen to make their home. Beyond the immediate household, all they had was their church and their community, the early bonds of law and society they were building, and the dramatic success of European colonisation of North America should not blind us to how precarious those early days were.

What was the liberty that Anne Hutchinson stood for? Not just to believe what she wished to believe, and worship as she desired to worship, though that was threatening enough to a nascent settlement built upon uniformity and togetherness. Anne Hutchinson and her followers were, as historian Francis Bremer says, publicly maintaining that the views of the majority of the clergy were false, harmful to the spiritual welfare of the colonists, and should be prohibited

.

In an article for National Affairs, Carl Scott described five kinds of American liberty: natural rights; communitarian liberty; economic autonomy; social progressivism; and personal autonomy. In early seventeenth century Massachusetts, liberty was communitarian, bounded in scope by the needs of the community, yoked to the interests of all before the needs of the individual. Anne Hutchinson's liberty, the freedom she demanded (though not, theologically, a freedom she was ready to extend to everyone else), was very much of the final type, personal autonomy. This is the liberty, often couched as a sacred right, to do as you want regardless of the consequences for others, the liberty enshrined within a Covenent of Grace. The liberty beloved of the Second Amendment advocates demanding the right to bear any arms their arms are capable of bearing, or of anti-abortion legislators, or of legislators who denounce any restirction upon their right to exclude anyone they want from the franchise, from full participation in civil society.

This was the liberty John Winthrop denounced in 1645 as liberty to do as one wished, evil as well as good

. Definitions of evil and good vary from time to time and from person to person, but most conceptions of liberty allow for some constraining authority, be it (in an American context) the law, the Constitution, or the Bible. To the Puritans the Bible was the absolute authority, but in her trial transcript Anne Hutchinson claimed the precedence of personal revelation, the direct word of God to her. She, and anyone who shared her vews, were literally above the law, beyond the social contract, and no longer subject, even, to Scripture. Her uncompromising devotion to her personal faith and refusal to be bound by a consensus she felt to be unjust, even evil, made her a Puritan's Puritan, and like the Puritans she left behind, she took the wilderness over a corrupt world. And the wilderness took her.

The only real difference between the Sane and the Insane, in this world, is the Sane have the power to have the Insane locked up.

Hunter S. Thompson

Bibliography

- Barker-Benfield, Ben. 'Anne Hutchinson and the Puritan Attitude toward Women.' Feminist Studies 1, no. 2 (1972): 65–96.

- Bremer, F. (2009) Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

- Kaufmann, M.W. 'Post-Secular Puritans: Recent Retrials of Anne Hutchinson.' Early American Literature 45, no. 1 (2010): 31–59.

- LaPlante, E. (2005) 'A heretic's overdue honor' The Boston Globe, 7 September 2005.

- McKenna, G. (2007) The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism, London, Yale University Press.

- Morgan, Edmund S. 'The Case against Anne Hutchinson.' The New England Quarterly 10, no. 4 (1937): 635–49.

- Porterfield, A. 'Women’s Attraction to Puritanism.' Church History 60, no. 2 (1991): 196–209.

- Schneider, D. 'Anne Hutchinson and Covenant Theology.' The Harvard Theological Review 103, no. 4 (2010): 485–500.

- Scott, C. 'The Five Conceptions of American Liberty.' National Affairs 49, Fall (2021).

- Withington, A, & Schwartz, J. 'The Political Trial of Anne Hutchinson.' The New England Quarterly 51, no. 2 (1978): 226–40.

- Zinn, H. (2003). A People's History of the United States. New York, Harper Perennial.