Untying the knot

The tangled roots of colonial Virginia

Our hands which before were tied with gentleness and fair usage, are now set at liberty by the treacherous violence of the Savages…

Edward Waterhouse

The great Powhatan chief, Wahunsenacawh, did not attend his daughter's wedding to John Rolfe. Perhaps his trust, or forgiveness, towards her new family (who had, after all, kidnapped her a year previously) did not extend that far, or perhaps he was too sad to see her go, but two of her brothers, and her uncle Opechanacanough are present for this symbolic union. It meant peace, an understanding and equilibrium with the English, maybe even a victory, a new status quo. But for the Jamestown settlers and the Virginia Company it was nothing of the sort. This was just the beginning.

There was no gold to be scooped from the seashores, nor easy passage to the southern ocean to be found, so the Company dug in for the long game. It had already pivoted its sales pitch, selling patriotism, an England overseas, an empire, had expanded its remit 'from sea to sea' and into the ocean, encompassing Bermuda and from 1616 it aggressively moved into the real estate business. Maybe it didn't matter if there was no gold in the ground, for the ground was gold. To the English land was, in the words of historian Bernard Bailyn, the chief measure of wealth, prestige and political importance

, and the Company had an unlimited amount. From 1614 the first settlers, those that had survived, began to claim their 50-acre private lots, and as tobacco cultivation spread the profit potential of land exploded. In 1616 1,250 pounds of tobacco were shipped to England: within the decade Virginian exports grew to over 400,000 pounds. From 1616 the Virginia Company offered 50 acres to any new migrants, or to any who would fund the passage of another, as it began to realise the financial potential of monopolising the supply of vital goods to its fledgling colony: Treasurer, Thomas Smythe, would only allow supplies to be paid for in tobacco, a practice which had done much to encourage piracy and smuggling among settlers who could not or would not pay his cut-throat prices

.

Edwin Sandys, a Member of Parliament, one of the Company's founders, and Smythe's successor as Treasurer from 1619, sought to reduce the colony's dependency on tobacco, and to diversify its productive capacity, recruiting glass blowers and iron workers, salt manufacturers and shipbuilders from all over Europe. The easy money had proved illusory but he envisaged a permanent colony, an expansion of England's territory, reach and power, a global market for English goods and an outlet for the mother country's surplus population. Emigrées came forth from all quarters of English society, though invariably more so of those who had least to lose – a more damned crew hell never vomited,

as Sandys said of the Jamestown general populace in 1623.

Tobacco was a labour-intensive crop so the demand for fresh bodies remains high. It cost around £6 to ship a body across the ocean, and one labourer could tend up to 2,000 tobacco plants potentially earning £80 a year. London constables were instructed to round up vagrant children from the city streets and send them to Bridewell Hospital detention centre, from where over 300 found themselves en route to Virginia. Similarly churchwardens solicitously enquired of poor households whether they were overcharged and threatened with poor children

, and if they weren't their poor relief would be suspended until they were more compliant. The Lord Mayor of London's Common Council was more than happy to send the wretched refuse of his own teeming shores into the tempest, to ease the burden on his city's coffers and enirch his own investment in the Virginia Company's bottom line. Women too were encouraged to travel so that settlers might start families and grow their own labour, and those that could not pay their way travelled at the Company's expense, and were sold to affluent husbands on the docks of Jamestown for some 150lb of tobacco.

The first boatload arrived in 1619, a banner year for human trafficking as it also saw the sale of 20 and odd Negroes

on 20th August. They were part of a shipment of several hundred men, women and children captured by Portuguese slavers in the Ndongo Kingdom of West Africa (in modern-day Angola), and transported across the Atlantic in the San Juan Bautista, bound for Veracruz but waylaid by two English privateers. Nearly half of this cargo died on the crossing, but of the 200 that were subsequently seized by the English vessels, 20 from the White Lion were traded for food supplies. Slavery didn't exist in the Virginia colony - it was one of the many Spanish practices they reviled - so they were sold as indentured servants instead. The Jamestown settlers had already used captured Indians as forced labour (slavery didn't exist in the Virginia colony), but it was all too easy for them to escape: these Africans stolen and deposited on a foreign shore thousands of miles from their homes, with neither ties nor language in common with the native tribes, would prove much more pliable and profitable. Unfortunately slavery didn't exist in the Virginia colony, but 1619 also saw the first election of Virginian lawmakers, known as burgesses, which was the first representative assembly founded among in the European colonies. These men would pass laws to suit their own needs, their own social norms and economic priorities, the beginnings of a long and eventful divergence between the colonies and the distant metropolis in England.

More boats arrived, bearing more settlers, whether their crossings were undertaken willingly or not. Conditions on the voyages remained crowded, dangerous, filthy, and often fatal: of the 180 or so of his congregation that sailed with Francis Blackwell from Amsterdam in the winter of 1618-19, around 130 died at sea, including Blackwell himself. Those that made it to Virginia often arrived in the oppressive heat and humidity of a Chesapeake summer, to learn that the guesthouses and residences of which they had been assured did not exist. Jamestown itself remained a collection of dilapidated wooden hovels huddled behind the defensive pallisade, but the settlement was booming, its reputation for enormous excess of apparel and drinking

such that the Company in London sent orders banning such wild extravagance and provocative clothing.

From Fort Comfort at the mouth of the James to an expanding diaspora reaching 100 miles upriver,wealthy newcomers and freed servants alike founded their own private plantations. These ranged in scale from a few hundred acres to vast semi-independent settlements like St Martin's Hundred, 21,500 acres housing 250 settlers from 1618 centred around the fortified clutch of wooden cabins known as Wolstenholme Town. Most still lived in wattle and daub homes though, one or two rooms at the most with dirt flors and thatched roofs, and half of those who had come to St Martin's were dead by 1621, from violence, from disease, from malnutrition or ultimately from exhaustion. Yet some thrived: George Thorpe, another former Parliamentarian, wrote from the Berkeley plantation in 1620 that he had never been in such good health, that food was plentiful, the colony prosperous, and the liquor excellent. Amid this scene of haphazard unchecked expansion and the growing encroachment of tobacco plantations through the Tidelands, the boundaries between English and natives blurred: the Company's new rules forbade any injurie or oppression

against indigenous tribes, and colonist and native alike often visited each other's settlements. The industrious George Thorpe even built an English style home for Opechanacanough, who had become the chief of the Powhatan in 1618, with which the new ruler was delighted, especially in his lock and key, which he so admired, as locking and unlocking his door an hundred times a day

.

And yet for all these overtures, the gifts, the visits, the schools the English might build, it was increasingly clear to the Powhatan that the settlers were here to stay, and that no matter the deaths they endured they would only grow in number. Any hopes they might have harboured were dashed by the report of one of Opechanacanough's counsellors, Uttamatomakkin, who returned from a voyage to England with John Rolfe and Pocahontas in May 1617. Uttamatomakkin had harsh words to say about the disdain the English had shown him, and the contempt they displayed for native religious beliefs, but worse than that, worse even than the news that the princess Pocahontas had taken ill and died before leaving, was his frank estimate of the numbers of white people he saw on his travels. When asked to gauge their strength, he told Opechanacanough to count the Stars in the Sky, the Leaves upon the Trees, and the Sand on the Seashore, for so many people… were in England

. To the Powhatan chieftain, this vision of the future held little room for his people and their way of life. They would be displaced, or they would be destroyed. He would bide his time. He would let the English spread out, grow confident, complacent. And he would act.

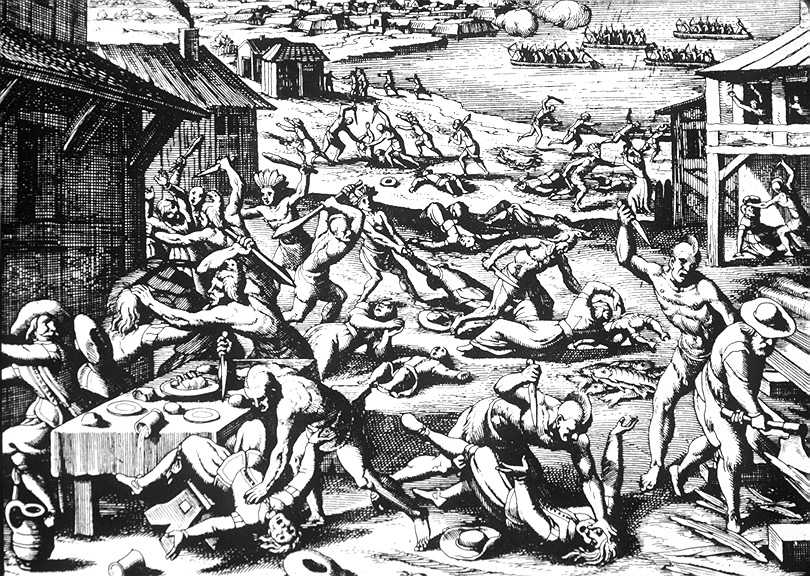

The morning of 22 March 1622 dawned like any other. Native workers and traders strode into the English settlements and plantation houses, they took up their places in the fields or joined their hosts at the breakfast tables, they worked, they ate, they talked and they haggled. And, a little before noon, they attacked. With hidden weapons or any that lay to hand, they killed every settler they could find, not sparing eyther age or sexe, man, woman or childe; so sodaine in their cruell execution that few or none discerned the weapon or blow that brought them to destruction

.

And by this means that fatal Friday morning, there fell under the bloody and barbarous hands of that perfidious and inhumane people, contrary to all laws of God and men, of Nature & Nations, three hundred forty-seven men, women, and children, most by their own weapons; and not being content with taking away life alone, they fell after again upon the dead, making as well they could, a fresh murder, defacing, dragging, and mangling the dead carcasses into many pieces, and carrying some parts away in derision, with base and brutish triumph.

Edward Waterhouse

Jamestown itself survived the assault. A native boy who lived with Richard Pace as a son

in a farmhouse some three miles from the fort chose to alert his master rather than kill him, and Pace hastily rowed across the James and ran to the fort to warn the Governor. The gates were closed, the guards forewarned, and messages sent hastily to the other settlements. For the most part they came too late. George Thorpe and at least 60 others at Henrico were slain, the ironworks destroyed; 74 died at St Martin's Hundred, and many many more in the far-flung farms as the Powhatan endeavoured to completely exterminate the entire colony. Survivors fled behind the pallisades of Jamestown, they and their cattle huddled behind the walls, their fields untended and food stocks low, since corn had been long neglected in favour of the quick profits tobacco promised.

Almost 350 settlers had died. Outlying plantations were abandoned, others fortified as those who remained fell back eastwards. Their position was desperate, their retaliation brutal. Starving themselves, their spring planting season lost, they targeted native supplies, siezing what they could and burning the rest. As yet more shiploads of new arrivals landed amind this scene of devastation, famine swept the colony, worseend by the lack of tobacco with which to pay for more supplies. At least 500 more died in the year after the attack as famine and disease took their toll, so much so that George Sandys (brother of the Company Treasurer Edwin, he had sailed to Virginia in 1621 hoping for some time to devote to his translation of Ovid's Metamorphoses) spoke of the living being hardlie able to bury the dead

. Letters home from the newly-arrived Richard Frethorne, begging for relief or return, bragged lyrically of his misery, of his most miserable and pitiful case, both for want of meat and want of clothes

, of the scurvy and the bloody flux and diverse other diseases, which maketh the body very poor and weak

, and that there is nothing to be gotten here but sickness and death

. The colonists gave as much as they got. In 1623 a Captain Daniel Tucker opened up peace negotiations with the Patawomeke tribe, during which he took the opportunity to slaughter some 200 of them with poisoned wine. Not content with that total he then returned and killed som 50 more and brought hom parte of their heads

.

Instead of a Plantation [Virginia] will shortly get the name of a slaughter house, and so justly become odious to ourselves and contemptible to all the world.

Nathaniel Butler, The Unmasked face of our Colony in Virginia

The Company's goals of trade and cooperation with the native tribes had failed. Edwin Sandys' planned economic enterprises – silk production, iron, glass, grape and timber – had failed. Of the 8,000 or so men, women and children who had sailed to Virginia, the 1625 census recorded a population of only 1,218. Their fundraising lotteries had been banned by the Privy Council, and English tobacco imports now subject to duties. (King James loathed smoking. And, for that matter, Edwin Sandys.) Deeply in debt, the Company seized upon the sudden rush of blood provoked by the 1622 attack to re-energise popular support - a necessary bloodletting to make the body more healthful

their report maintained as it proposed a pivot, its mission of civilisation becoming one of conquest. Reprisals are swift and brutal: this land is their land.

But it is the Virginia Company's no longer, for in 1624 the Company was dissolved. The debts, the bodies, the plaintive letters from the likes of Richard Frethorne and even damning testimony from George Sandys, never mind the dusted-off greivances of Captain John Smith, the evidence mounted up from all quarters. Sandys appealed to his powerbase in Parliament to save this Child of the Kingdom

, but the King forbade even consideration of his plea. Virginia became a royal colony, and the tobacco trade a royal monopoly. In spite of Sandys's, and possibly James' wishes, tobacco cultivation spread irrevocably up the river again as well as inland, production striving to rise faster than prices fell: at one point even the streets of Jamestown were planted with tobacco leaf. Native cornfields and villages were burned as vengeful settlers attempted to purify Virginia, but the bloom was definitely off the rose as English hopes and hagiography shifted their attentions to a new colony to the north. To a venture funded in part through an interest-free loan from Edwin Sandys, and sailing with charts drawn up by John Smith. An undertaking not of explorers, nor entrepreneurs, nor even patriots, but believers. They were making for the same place, but their conception of a new world was very different.

[England must conquer] …by force, by surprise, by famine, in burning their corn, by destroying and burning their boats, canoes and houses, by breaking their fishing weirs, by assailing them in their huntings, whereby they get the greatest part of their sustenance in Winter, by pursuing and chasing them with our horses, and bloodhounds to draw after them, and mastiffs to tear them, which take these naked, tanned, deformed savages, for no other than wild beasts.

Edward Waterhouse

Bibliography

- Bailyn, B. (2012) The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Brogan, H. (2001) The Penguin History of the United States of America (2nd ed.), London, Penguin.

- Hakim, J. (2003) Making Thirteen Colonies - 1600-1740 (3rd ed.). New York, Oxford University Press.

- Thornton, J. (1998). 'The African Experience of the "20. and Odd Negroes" Arriving in Virginia in 1619'. The William and Mary Quarterly, 55(3), 421-434.

- Wooley, B. (2007). Savage Kingdom. The True Story of Jamestown, 1607, and the Settlement of America. New York, Harper Perennial.