God's country

The strange death and life of Puritan America

The early settlers bequeathed to their descendants the customs, manners, and opinions that contribute most to the success of a republic. When I reflect upon the consequences of this primary fact, I think I see the whole destiny of America embodied in the first Puritan who landed on those shores.

Alexis de Tocqueville Democracy in America

You are the light of the world. A city that is set on a hill cannot be hidden.

Matthew 5:14

European philosphers and intellectuals still believed in utopia, in the discovery of a Promised Land and the realisation of a perfect society, and they continued to locate those hopes in the West. Since Thomas More's genre-defining Utopia in 1516, through The City of the Sun by Italian philosopher Tommaso Campanella in 1602, to Francis Bacon's New Atlantis in 1624, writers, thinkers and dreamers placed their hopes for idealised republics, religious liberties and post-materialist collectivism squarely across the Atlantic (although More cheerfully and presciently included slaves within his depiction of paradise. And as stories of successful settlement in the Americas spread through Europe, so did a great many sectarians and non-conformists set out for the rocky coasts of the New World to escape poverty and persecution at home, or to realise their personal visions of spiritual salvation. Of all these dreamers and believers, only one group stands shoulder to shoulder with the Pilgrims at the forefront of the American historical canon: the Puritans.

So close in fact that many confuse the two, but the Puritans were not Pilgrims. For one they came later, in 1630, in a fleet (11 ships carrying 700 passengers) led by the Arbella to the fledgling Massachusetts Bay Colony established in Salem in 1626 by Pilgrim settlers from Plymouth. And they came in much larger numbers, some 13,000 between 1630 and 1640 alone. And unlike the Pilgrims, they weren't looking to breakaway from their own church, but rather to perfect, to 'purify' it, to one day sail home and triumphantly reform the Church of England. In principle at least they had return tickets and were, according to historian Perry Miller, not battered remnants of suffering Separatists thrown up on a rocky shore but rather an organised task force of Christians executing a flank attack on the corruptions of Christendom

.

The Puritans were very conscious of History (with a capital 'H') and of their place within it. Their purpose was to weed out the ceremony and ornament from religious practice, to remove ritual, idolatry and corruption from England's Elizabethan religious settlement, and to return worship to its Scriptural fundamentals, to restore to every man his direct and personal relationship with God. John Winthrop, leader of the 1630 fleet, spoke to them of their covenant with God, and of the example they would set to all of Europe: in his writing Winthrop persistently referred to himself in the third person, as 'the Governor', with one eye firmly upon posterity and the examples the Puritans would impart, assured that posterity would be looking back.

History has obliged. This notion of Providential mission, of a sacred purpose underlying America's national destiny, has continued to imbue the national myth (and myths are, of course, very real). In his sweeping review of the influence of Puritanism upon American patriotism, George McKenna wrote that when the chips are down, when the stakes are high, American political leaders go back to the narrative and even the language of the Puritans

. Amid the throes of the Civil War Lincoln spoke of Americans as being an almost-chosen people

. In an address to US troops sailing for Europe in 1917, Woodrow Wilson affirmed that The eyes of all the world will be upon you, because you are in some special sense the soldiers of freedom

. Self-reliance, individualism, political liberalism, a robust Protestantism and a firm belief in a unique and achievable national destiny, this is the Puritan legacy laid down in seventeenth-century New England, described by Harriet Beecher Stowe as the seed-bed of the republic

.

Who were they, these mythmakers? Show me a Puritan and I'll show you a son-of-a-bitch

wrote H.L. Mencken. A people who hated bear-baiting not because it gave pain to the bear but because it gave pleasure to the spectators

in Thomas Macauley's opinion. And theocrats, regicides, witch-burners, Indian killers, and bigoted heresy hunters

in the popular imagination, according to their historian F.J. Brewer.

They were. for the most part, families. More so than the Pilgrims, and quite unlike the ambitious young men who set out to find their fortunes in Jamestown. They were devout, of course, extremely literate by the standards of the time (demonstrated by the proliferation of surviving sermons, letters, poems, laws and diaries, which have naturally endeared them to historians), and comparatively affluent. Their Great Migration of 1620-40 saw some 80,000 or so leave England for Ireland, the Netherlands, the West Indies and New England, motivated in the main by the opportunity to live and worship as they saw fit, and to practice a reformed Protestantism, a Calvinism, that had stalled and was stifled under the Elizabethan Church. They wanted to live within Godly communities ruled over by the elect, living under God's covenant, the only legitimate source of morality and religious practice. They came in search of the freedom to worship as they saw fit, which was not the same as freedom of worship. They did not reject authority, they only wanted to exercise their own. In Gore Vidal's word, they left England for America not because they couldn't be Puritans in their mother country, but because they were not allowed to force others to become Puritans; in the New World, of course, they could and did

. This was why the Great Migration ended (and indeed a large number of clergy in particular returned home) once the outbreak of the English Civil War raised the possibility of establishing Godly rule over England itself.

Massachusetts Bay was the wilderness the Godly had chosen over the sinful and corrupted society they left behind. They bore Godly names proclaiming their virtues – Patience, Faith, Constance – or acknowledging the spiritual struggle – Fear, or Wrestling-with-the-Devil). Expanding quickly from their initial walled stockades they built small towns (Greenfield, Springfield, and Longmeadow were early examples) based upon individual congregations of worshippers, centred upon large meeting houses and communal fields for grazing. The town of Boston, named after Boston in Lincolnshire, England, located on the Shawmut Peninsula, quickly grew to be the largest town (and would remain the largest in all the thirteen colonies until Philadelphia overtook it in the mid-eighteenth century) became the capital: the first public school in America opened there in 1635, and the mint began issuing its own coinage from 1652. Despite Winthrop's personal views over native land rights, namely that they enclose no Land, neither have any settled habitation, nor any tame Cattle to improve the Land, and so have no other but a Naturall Right to those countries, so as if we leave them sufficient for their use, we may lawfully take the rest

, the Massachusetts Bay Company explicitly charged their colonists with maintaining productive relationships with natives, and to avoid the least scruple of intrusion

. And initially the local tribes, the Massachusetts and the Pawtucket, were cautiously welcoming: like the Wampanoag they had been devastated by European plagues, their numbers massively depleted, and they faced threats from other tribes that compelled them to prioritise peace and trade with the English.

But for the natives in these parts, God hath so pursued them, as for 300 miles space the greatest part of them are swept away by smallpox which still continues among them. So as God hath thereby cleared our title to this place, those who remain in these parts, being in all not 50, have put themselves under our protection.

John Winthrop

The Puritans fenced in their livestock to keep them from the often-abandoned Indian cornfields, and made sure to purchase their land from native tribes in a manner which affored them at least a sense of fairness. They built waterwheels to power their mills, and traders, blacksmiths, innkeepers and candle-makers all plied their trades. Every town of more then 50 settlers was obliged to fund a school from the common purse, for every child had to learn to read the Bible, sometimes in Greek, Latin or even Hebrew (in smaller settlements it was the parents' legal obligation to ensure their children were literate). In 1636 the Massachusetts Bay General Court (a legislature elected by all male church members) founded Harvard College dreading to leave an illiterate ministry to the churches, when our present ministers shall lie in the dust

.

They worked hard, with a keen eye for property and profit, and played, well, less hard. Working and trading were not allowed on a Sunday, nor were games of any kind, not to mention intemperate pursuits like cooking, running or shaving, or making a bed, not that there would have been much time as Sunday sermons were measured by the hour, reluctantly conceding a break for lunch. They read the Bible every day. Celebrating Christmas was forbidden. Women were expected to keep the home, to look after children, and to birth many more. A wife was considered to be her husband's property, and one that ran away could be tried for her own theft. Scold's bridles were a regular punishment for the overly-opinionated wife, as were ducking stools for persistent offenders. After idolatry, the second capital crime proclaimed in the Massachusetts legal code of 1641 was witchcraft (followed by blasphemy, murder, poisoning and then bestiality): If any man or woman be a witch, that is, has or consults with a familiar spirit, they shall be put to death

. The provision applied to men and women both, but was applied far more to women who fell foul of their husbands, their neighbours or their community, many accused for as little as bearing the mark of the devil, be it a pimple, a wart or a mole.

With a world of sin at their backs and a wilderness full of savages prowling the pitch black New England nights, Puritan communities had to be strong, and their strength derived from their cohesion, their togetherness, their purity. As John Winthrop had proclaimed on the Arbella as they sailed the Atlantic, “We must knit together in this work as one man, mourn together, labor, suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, our community as members of the same body.

Only adult male church members participated in selecting the Governor and Council, that is those who had shared their own personal experience of conversion and Grace with their congregation, and from 1637 none could even settle within the Massachusetts colony without first having their othodoxy confirmed by magistrates.

The Puritans' insistence upon the collective strength and unity of their congregations combined with the primacy of the individuals' relationship with God was always going to be a problem. They hated Catholics, that was a given. They feared and loathed Quakers, whose belief in everyone's inner light leading them inexorably to God should have been a tight fit, but whose conclusion that this relieved them of the need to be told what to do by Church ministers didn't sit so comfortably. To Puritan authorities Quakers were a cursed sect

, and any that set foot in Massachusetts were met with whipping, banishment, mutilation, even execution, most famously Mary Dyer, in Boston on 1 June 1660. Nor could they tolerate those who preached toleration of such heresies, hence the banishment of minister Roger Williams in January 1636. From the opposite flank their orthodoxy was undermined by those whose personal revelation from God challenged the wisdom and authority of their ministers, for which offence Anne Hutchinson and many others were exiled in 1638.

Outwardly relations were even more fractious. For all the good diplomatic intentions of the Company Charter, trade and settlement expanded, inciting tensions between native tribes as well as between English and Dutch merchants. Monopolies over local markets meant money, while land was wealth, status, power, and here was more than they could have dreamed of, forests without end to be cut, farmed and conquered, proof if more were needed that these were God's chosen people and this land was their bounty. While native tribes had long fought one another over territory, the colonists' notions of ownership and exclusivity were alien to them. Treaties in which the English 'bought' land may have been understood as a right of access by the local tribes, but to settlers steeped in feudal traditions, in estates and enclosure, it was ownership, exclusive and in perpetuity: this land was their land, and no-one else's.

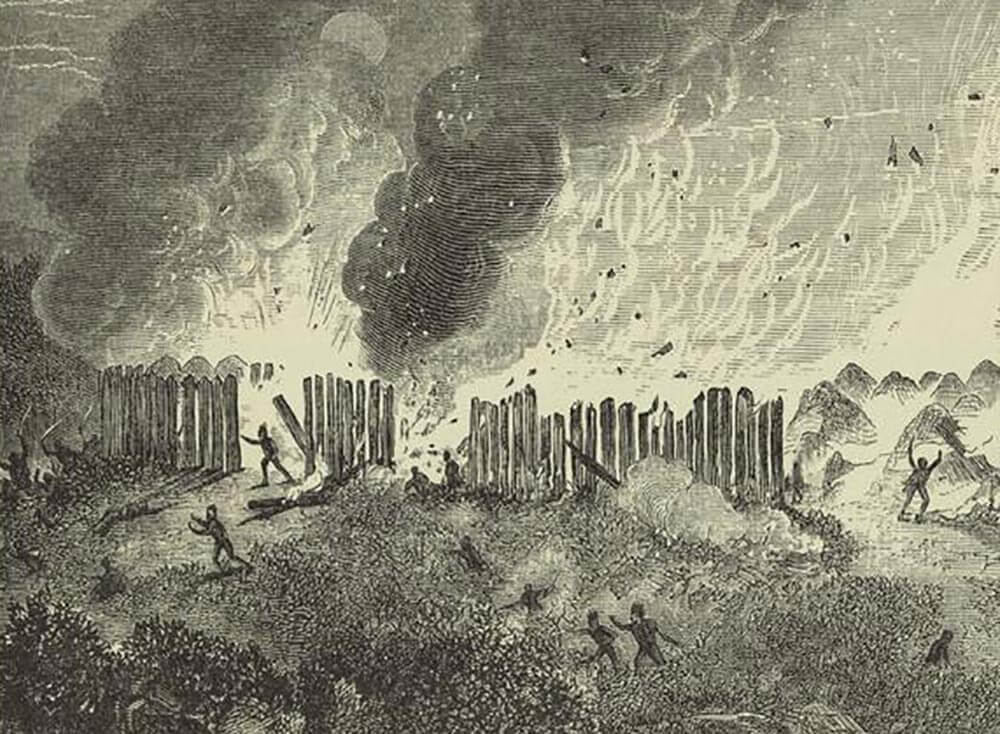

As English settlement expanded into the Connecticut River Valley, conflict between the English-allied Mohegan tribes and the Dutch-allied Pequot, and the devastating effect of an epidemic in 1633-34, came to a head in the Pequot War of 1636-38. The Pequot themselves had taken these forests from the Naragansett, Mohegan and Wampanoag, until smallpox devastated their numbers, killing up to 80%. Sporadic violence between Pequot and traders led to reprisal attacks by the Massachusetts Colony on several villages, and then a Pequot seige on the Saybrook Colony (founded in 1635 at the mouth of the Connecticut River by John Winthrop the Younger, who was a chief instigator of the founding of the Connecticut Colony in 1636) and raids on nearby towns which killed around 30 settlers.

The English response was swift and decisive. A militia raised by the Connecticut towns led by Captain John Mason, reinforced by men led by John Underhill from Massachusetts Bay and including Mohegan and Naragansett warriors, marched on the Pequot fort near the Mystic River. The pallisaded walls were strong and its defences more than enough to deter a frontal attack, so the Puritan forces blocked the two exits and burned the entire village to the ground. Any Pequot trying to climb the walls to escape were shot, and those that made it out of the gates were cut down and butchered. Of some 400-700 Pequot in the fort, mostly civilians, only a handful survived: the slaughter was indiscriminate and near-enough absolute. As John Underhill recorded, sometimes the Scripture declareth women and children must perish with their parents... We had sufficient light from the Word of God for our proceedings

.

Those that scaped the fire were slaine with the sword; some hewed to peeces, others rune throw with their rapiers, so as they were quickly dispatchte, and very few escaped. It was conceived they thus destroyed about 400 at this time. It was a fearful sight to see them thus frying in the fyer, and the streams of blood quenching the same, and horrible was the stincke and sente there of, but the victory seemed a sweet sacrifice, and they gave the prayers thereof to God, who had wrought so wonderfully for them, thus to inclose their enemise in their hands, and give them so speedy a victory over so proud and insulting an enimie.

William Bradford History of the Plymouth Plantation

In the aftermath of this massacre, the remaining Pequot soldiers and refugees were quickly hunted down or captured. Some were granted as slaves to the Mohegan and Naragansett, others shipped to the colonial plantations in Bermuda or the West Indies, or kept as house slaves for settler familes: the Pequot tribe were erased and their lands dispersed among the victors. It would be almost forty years before New England tribes again waged war upon the English, for the English fought a European-style total war, not for honour or lands but for survival: their victories were absolute and the stakes, the native chiefs came to realise, were everything.

Compared to the struggles, the pivots, the brushes with disaster, and the deaths experienced by setlers in Virginia, the New England colonies seemed to have it all, and yet the early Puritans and Pilgrims both met with similar disappointments. And as their aspirations had been more spiritual than the Virginia Company's, so too were their failures. The Puritan triumph in England, their victories in the Civil War and execution of King Charles in 1649 proved short-lived, and Charles's son was crowned King Charles II in 1660. The powers of colonial governments to impose their own brand of worship and punish dissent were curtailed, but the malaise was more fundamental, more internal than this.

The stark truth was that of the many thousands to cross the Atlantic to the Massachusetts Bay, most did so not to realise the kingdom of heaven, but simply to better their lot on earth. They can for land and opportunity, to enjoy the fruits of their labours and build better for their children. As the founding generation of leaders grew older, they succumbed to a resentment and disdain for the next wave of settlers who did not share their values, and their attempts to compel conformity and enforce their standards resulted in their transformation, in Paul Heike's words, from an oppressed minority of non-conformist believers into an oppressive ruling elite

. They also failed.

The 1660s saw a flurry of laws prohibiting new trends, such as the wearing of lace, or indecent and revealing slashes in clothing, or ostentatious silver or gold jewellery, and a new kind of sermon (or a rather a new manifestation of one of the oldest kinds of sermon), the jeremiad, denouncing corruption, backsliding, and decline in favour of renewal and reaffirmation of the community's original purpose. In spite of this, or because of it, church membership declined. As the colonies settled and cohered into safer, more stable towns, and the frontier receded, so a more worldy individualism began to flourish in New England as in Old. John Winthrop died in March 1649 as the Puritan cause in England reached its fullest triumph. William Bradford, who continued to govern the Plymouth Colony for most of his life until his death in 1657, wrote more openly in his later years of his disappointment, of the colony's failure to fulfil its original purpose and his growing sentiments of damnation and despair at the succeeding generation, his questioning that the Pilgrims had ever really left the wilderness they had sought to cross.

To the Godly, the dream of a purified Church, of lighting a candle that might never go out, may have been extinguished before it ever really began, but for most settlers, old and new alike, this sense of mission, this preoccupation with salvation or damnation, was less acute. To them, as historian Patricia Caldwell wrote, it was an America neither of joyous fulfilment nor, on the other hand, of fearsome, howling hideousness, but a strange foggy limbo of broken promises

. They came not to build a kingdom but a house, a farm, an opportunity denied them in the towns and villages from which they sailed. They came, as historian James Truslow Adams, summarises for the simple reason that they wanted to better their condition. … They wanted to own land; and it was this last motive, perhaps, which had mainly attracted those twelve thousand out of sixteen thousand who swelled the population of Massachusetts in 1640, but were not church members.’

And yet it is the Puritans who, like the Pilgrims, have claimed such undue prominence within the national narrative, the founding fathers of American exceptionalism. Why? They were not just undemocratic - hardly unusual for the time - but anti-democratic: John Winthrop described it as the meanest and worst of all forms of government

and as a manifest breach of the 5th Commandment

. They were profoundly collectivist as they struggled to build a viable community beyond the edges of Christian civilisation, as the Governor again decreed: The care of the public must oversway all private respects… We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of others' necessities

. And, following the Calvinist theology of their time, a central tenent of reformed Protestantism, they believed in predestination, that from the moment of birth the Chosen were already elected, that God knew who was bound for Heaven and who condemned to Hell, and that nothing a person did in their lifetime, no amount of good works or deeds or prayer, would or could make the slightest difference to this pre-ordained outcome. Could there be anything less American?

And yet. Do historians like Puritans because they were so literate, because they left reams of thoughts and sermons and ideas and evidence to pour over? Because they were, as historian Philip Fisher concedes, a mirror filled with familiar features… a society in which the critics and intellectuals were not marginal, but actually in power

? Does modern society see them as the idealised, archetypal Americans - men, women and children who hacked a new life out of the wilderness, who built this great country by virtue of hard-work and self-reliance, the much-vaunted Protestant work ethic? The architects of the land of opportunity, who risked everything to build a better world? It's an appealing line of reasoning, but then couldn't the same be said of most immigrants, be they from the shores of Essex or the Netherlands, or from Poland, China, Mexico or Afghanistan, from the seventeenth century or the twenty-first? If so, the enthusiasm and affection extended to tempest-tossed emigrés yearning to breathe free has cooled substantially in the centuries since the Mayflower and Arbella made their own landfalls. Pilgrims and Puritans make for a tidier origin story too - white, European, and Protestant – a past that feels more palatable, more recognisable to those threatened by the imminent erosion of white people's demographic majority in the United States. Annually celebrated, frequently condemned, but rarely ignored, Puritanism is written indelibly across the history of America, even more so across its historiography, a light that continues to burn brightly. One that continues to dazzle more so than it reveals.

God preordained, for his own glory and the display of His attributes of mercy and justice, a part of the human race, without any merit of their own, to eternal salvation, and another part, in just punishment of their sin, to eternal damnation.

John Calvin

Bibliography

- Bercovitch, S. (1978) 'The Typology of America's Mission.' American Quarterly 30(2), 135-55.

- Bremer, F. (2009) Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction, New York, Oxford University Press

- Brogan, H. (2001) The Penguin History of the United States of America (2nd ed.), London, Penguin.

- Freeman, M. (1995) 'Puritans and Pequots: The Question of Genocide.' The New England Quarterly 68(2): 278–93.

- Hakim, J. (2003) Making Thirteen Colonies - 1600-1740 (3rd ed.). New York, Oxford University Press.

- McKenna, G. (2007) The Puritan Origins of American Patriotism, London, Yale University Press.

- Meuwese, M. (2011). 'The Dutch Connection: New Netherland, the Pequots, and the Puritans in Southern New England, 1620—1638.' Early American Studies, 9(2), 295-323.

- Morison, S. (1954). 'The Plymouth Colony and Virginia.' The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 62(2), 147-165.

- Paul, H. (2014). 'Pilgrims and Puritans and the Myth of the Promised Land.' The Myths That Made America: An Introduction to American Studies (pp. 137-196). Bielefeld, Transcript Verlag.