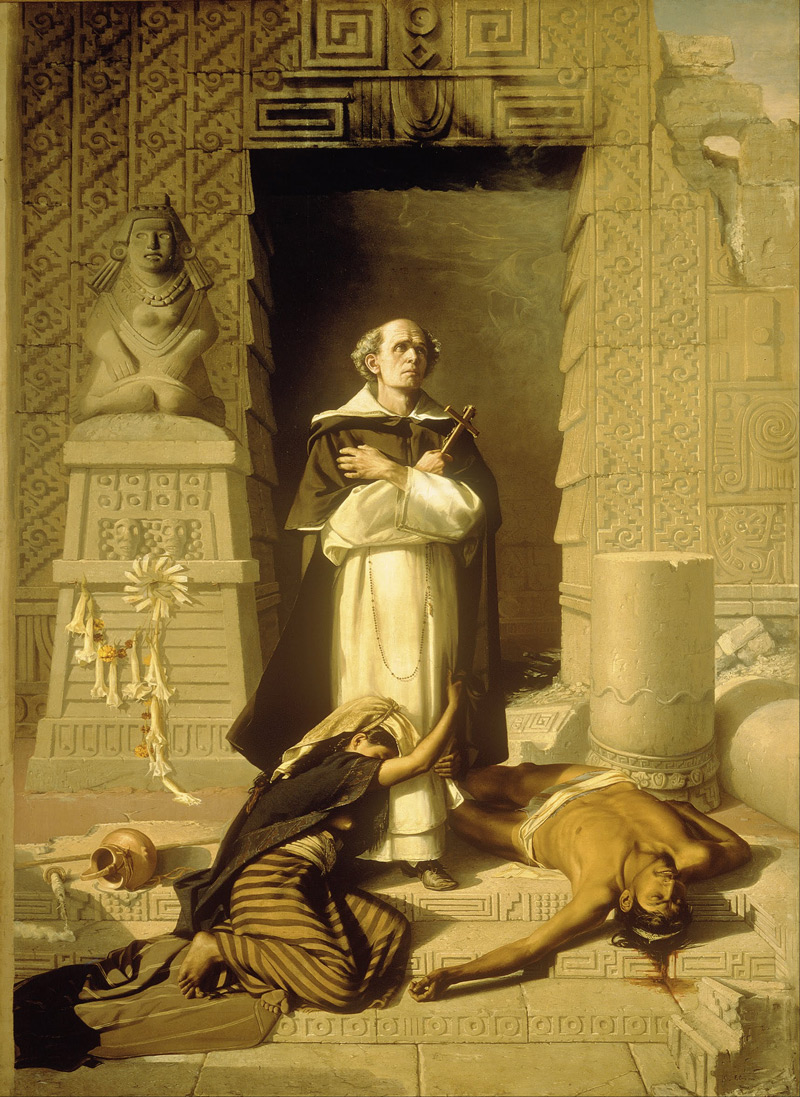

The just and the damned

Bartolomé de las Casas

Born 1484, Seville, Spain | Died 1566, Madrid, Spain

Colonist & Dominican Friar, Bishop of Chiapas, Protector of the Indians

The Spaniards first set Sail to America, not for the Honour of God, or as Persons moved and merited thereunto by servent Zeal to the True Faith, nor to promote the Salvation of their Neighbours, nor to serve the King, as they falsely boast and pretend to do, but in truth, only stimulated and goaded on by insatiable Avarice and Ambition, that they might for ever Domineer, Command, and Tyrannize over the West-Indians, whose Kingdoms they hoped to divide and distribute among themselves.

Bartolomé de las Casas

Bartolomé de las Casas, conquistador, encomiendero, and Defender of the Indians, has been many things to many people. He is feted by some as an early campaigner for the idea of universal human rights, and hated by others as an advocate for, even the initiator of, the transAtlantic slave trade. Most of all, he is remembered as a witness, a man whose many volumes of testimony helped shape contemporary and historical attitudes to the growing Spanish empire. He was an author, an advocate and a campaigner: he had an agenda.

Las Casas first sailed for Hispaniola in 1502, and in 1510 became the first priest to be ordained in the New World, whereupon he served as a chaplain in Diego Velázquez de Cuella's and Panfilo de Narvaez's bloody conquest of Cuba, seeing 'cruelty on a scale no living being has ever seen or expects to see.' This didn't stop him from enjoying the fruits of a rich encomienda as his reward however, and it was only later that he became convinced of the error of his own and his people's ways. This he attributed in part to the excoriation of a Dominican Friar who had visited in Hispaniola in 1511, and demanded of the colonists how they could be both slave owners and Christians (and who was immediately repatriated at their demand), and also to a close reading of Ecclesiastes in 1514, in particular a verse denouncing 'men of blood'.

Thereafter Las Casas travelled extensively around the Spanish colonies, and repeatedly back to Spain, in his efforts to temper the cruelties of his countrymen and to urge the Crown to intervene to protect natives from the exploitation and brutality of its emissaries - he was a firm believer in the just authority of Spain over the New World, but he was convinced that with authority came the moral obligation to protect all their subjects from the greed and brutality of agents acting far beyond their oversight. Las Casas was instrumental in the selection of new commissioners to govern the Indies in 1516 and the passing of the New Laws in 1542, both of which failed to bring about any real change in the colonies themselves.

Of more lasting impact were his writings, eyewitness accounts (not always his eyes - often he has to rely on second-hand accounts from those corners of the empire he never managed to visit himself) of the genocide carried out upon the Indian peoples. His History of the Indies, written between 1527 and 1561, document six decades of Spanish misrule, while the Apologetic History of the Indies was a section of that published as a standalone ethnographic treatise on the lives of various Native American tribes. It is the Short Account of the Destruction on the Indies, written in 1542 for Spanish King Philip II, that cemented his reputation, for better or worse, a succinct and vivid account of the Spaniards' bloody swathe of pillage, rape and murder across the Americas. It was this in particular that led to Las Casas being reviled in Spain as a heretic and a traitor in the years after his death, and even in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a fantasist, a propagandist, and a lunatic. In the seventeen century his works were most keenly distributed by the British and Dutch promoting the 'Black Legend', the notion that the Spanish were uniquely cruel and barbarous, unfit to rule over other nations either in the New World or the Old (which would of course leave the British and/or Dutch free to step in and take their place.

Las Casas was no dispassionate observer, never an impartial recorder of the facts, and if he is remembered as a witness it ought not, perhaps, to be as a reliable one. His casualty figures in particular have been widely contested: "...nor do I conceive that I should deviate from the Truth by saying that above Fifty Millions in all paid their last Debt to Nature." There is no way to accurately estimate the pre-Columbian population of the Americas, and neither could Las Casas, but the idiom in which he wrote was one which routinely exaggerated such numbers for rhetorical effect. The substance of his reports however, the atrocities related and the casual cruelties he laments, were certainly based in fact, and repeated by other accounts from friars, priests, even the perpetrators themselves. Las Casas compiled this litany of horrors for a reason, 'to make known to all Spain the true account and truthful understanding of what I have seen take place in this Indian Ocean', for he feared for the souls of his people, for the integrity of the empire. Similarly the widespread publication of his works in the seventeenth century had a motive, albeit the opposite one, to bury the Spanish empire, as evidenced by the subtitle his Short Account was circulated under: "POPERY, Truly Display'd in its Bloody Colours: Or, a faithful NARRATIVE OF THE Horrid and Unexampled Massacres, Butcheries, and all manner of Cruelties, that Hell and Malice could invent, committed by the Popish Spanish Party on the inhabitants of West-India..."

This was not the outcome Las Casas had desired, though it was one he feared: he donated his magnum opus, the History of the Indies, to the Collegio de San Gregorio in Valladolid, where he spent most of the last decades of his life, with the instruction that it not be published for at least 40 years for fear of the damage it might cause to both his own reputation and that of Spain (it was not actually published until 1875). That his words were siezed upon by Spain's enemies is hardly a surprise, for Casas's works, especially the Short Account, were not histories in any meaningful sense of the word, they were accusations. They are fine historical sources, so long as one is aware of their provenance and intent, but their purpose was not to explain why the Spanish settlers did what they did, nor to understand their actions, just to condemn, to pass judgment, the purview of a priest perhaps but not that of a historian. He hoped that the sentence might lead to some form of rehabilitation of the Spanish empire, while later distributors were more interested in a death penalty, but it was judgment all the same.

Nay, we dare boldly affirm, that during the forty years space, wherein they [the Spaniards] exercised their sanguinary and detestable tyranny in these regions, above twelve millions (computing men, women and children) have undeservedly perished; nor do I conceive that I should deviate from the truth by saying that above fifty millions in all paid their last debt to nature.

Bartolomé de las Casas

Las Casas's place in history is often as a corrective, a counterbalance to the Eurocentric 'Great Men' school of thought that celebrates Columbus and the Age of Discovery, but castigating Columbus and his fellows for the deaths of nameless millions serves as little purpose as glorifying their forging of a New World. Historiographers have long debated the utility of moral judgments in the writing of history, be it the advisability of deriving instructive examples from our ancestors or the worth of determining the rights and wrongs of their actions. Lord Acton (he of the 'power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely' dictum) thought such pronouncements an absolute necessity, and Isiah Berlin found the practice of history to be 'rife with moral presumptions and judgments, as well it should be'.

Others have questioned the usefulness, even the existence, of objective moral principles independent of particular times and particular cultures, suggesting that historical moral judgments are, by definition, anachronistic. As Marc Bloch asserted in The Historian's Craft, 'we can neither condemn nor absolve without accepting a table of values which no longer refers to any positive science. That one man has killed another is a fact which is eminently susceptible of proof. But to punish the murderer assumes that we consider murder culpable, which is, after all, only an opinion about which not all civilisations have agreed.' Even were there some absolute moral code to which all might be subject, what is the worth of weighing the rights and wrongs of actions committed long ago, the perpetrators of which are long past punishment or redemption? It is a poor sort of history that relies on labels as insubstantial as 'good' or 'bad' as if they are enough to explain why people did what they did and why events turned out as they have.

But Bartolemé Las Casas's histories have vastly increased our understanding of the early Spanish empire, for no matter how dramatically they might have been rendered, his portraits were painted from life. They are also evidence of an ethical dimension it might otherwise be easy to overlook, for while it may not be the historian's task to determine right from wrong (as opposed to true from false), nevertheless our ancestors were not morally deficient: they deliberated their own right and their own wrong, especially those that believed an eternity of heaven or hell was riding on the balance sheet, and this informed their actions, their explanations and rationalisations, and the world in which they lived. The Spanish settlers were not uniformly pillagers and conquistadors, nor were they all blind to the human cost of their civilising duty. Some turned from the slaughter, some railed against it, and some devoted their lives to trying to change things. Maybe they didn't succeed, though no-one can know what influence they had or how different events might have been without them, but they remain part of the story, evidence that no nation has ever held a monopoly on morality and that no era should imagine its own ethical sensibilities to be either uniquely-developed or final.

Are we so sure of ourselves and of our age as to divide the company of our forefathers into the just and the damned?