The Curse of Midas

The wane in Spain

At this time, they stripped the heir to his skin, and anointed him with a sticky earth on which they placed gold dust so that he was completely covered with this metal. They placed him on the raft … and at his feet they placed a great heap of gold and emeralds for him to offer to his god … when the raft reached the centre of the lagoon, they raised a banner as a signal for silence. The gilded Indian then … [threw] out all the pile of gold into the middle of the lake, and the chiefs who had accompanied him did the same on their own accounts. …With this ceremony the new ruler was received, and was recognised as lord and king. This is the ceremony that became the famous El Dorado, which has taken so many lives and fortunes.

Juan Rodriguez Freyle, 1638

At first El Dorado was a man: El Hombre Dorado (the golden man), or El Rey Dorado (the golden king). The phrase referred to a king, a chief of the Muisica (a tribe that lived in modern-day Colombia) who was covered from head to toe in gold dust as part of his coronation ceremeony before being submerged in Lake Guatavita. The man became a myth, a myth subject to heavy inflationary pressures, and soon El Dorado was a golden city, and later a kingdom, even an empire.

Myths are myths, but the gold was very real. The Inca referred to it as 'the sweat of the sun', and silver was 'the tears of the moon', and they prized both. Their emperor Atahualpa had a (somewhat) portable throne of solid gold that supposedly weighed 183 pounds. But though the Aztecs and Inca each decorated their homes and persons with jewellery and ornamentation wrought from precious metals, and demanded it as tribute from vassal tribes, they didn't value it quite as highly as the Spanish did: as barter economies, they had no concept of money. So they were taken aback by the conquistadors prodigious' demands for yet more and more gold and silver, leading some to conclude that they must feed it to their horses to keep these wondrous beats in service, so insatiable was their appetite. 'Even if all the snow in the Andes turned to gold, still they would not be satisfied' lamented Manco Inca Yupanqui, one of the Spaniards' puppet emperors who later rebelled against their rule.

And so the legend of El Dorado was irresistable to the invaders, and it was to draw thousands of men deep into the lush jungles of the continent, across vast and barren deserts, and into the distant, frozen peaks of the Andes mountains. A great many of them never returned. In 1535 the conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar sent a party in search of the Dorado valley in pursuit of a rumoured horde, and in 1536 a Spanish army invaded Muisica territory, where they first heard of the legends of the golden king of Lake Guatavita. Lázaro Fonte and Hernán Perez de Quesada duly attempted to drain said lake with buckets (and a lot of native labour) in 1545, while in 1580 Antonio de Sepúlveda tried digging a channel into its side to drain its water level, managing to drop it by around 20 metres before a collapse that killed many of his labourers. Sepúlveda uncovered gold, jewels and armour to the tune of approximately 12,000 pesos (upwards of $300,000 in modern money), some of which was duly despatched to Philip II back in Spain, but he himself died in poverty and was buried nearby.

After the conquests began the cupidity of the mines. For a time, and so long as the goods which the gold and silver were used to purchase were hers, these yielded great benefits to Spain. Subsequently, however, when we should have adjusted ourselves to the demands of the time, applied ourselves to agriculture and learned how to usefully employ human labour, we have simply continued to draw an infinite quantity of treasure from the ground which has only gone to enrich other nations.

José de Campillo y Cossío

While fortune-hunters continued to chase whispers and hearsay, real fortunes were there for the taking, plundered, stolen, and plucked from the ground, and despatched back to Spain in vast treasure fleets: as historian Felip Fernández Arnesto wrote, 'The government in Madrid, which had taken no direct part in the conquest of America, and had expended neither soldiers nor ships in the enterprise, woke up to find itself master of the richest continent in the world'. Quite how rich was becoming apparent. For almost 30 years after the discovery of the New World, the Spanish had remained largely confined to the Caribbean. Then came aggressive expansion, most famously the conquests of Cortés and Pizzaro, and then the mines. Native tribes had long mined precious stones and metals for decoration, status and tribute, but the Spanish scaled up to commercial extraction that was to reshape the economy of the entire world. From the Mexican silver mines established in the Tlachco (now Taxco) in the 1530s by Cortés and his men through to the massive silver deposits discovered at Zacatecas (1546) and Guanajuato (c.1558), the Viceroyalty of New Spain (to which the Spanish Crown claimed all subsoil rights) generated an enormous and ongoing flow of income to the mother country.

Potosí was a mining town founded in 1545 in the Viceroyalty of Peru (it is located in modern-day Bolivia), after a native American named Diego Gualpa discovered a rich seam of silver ore while climbing the Cerro Rico (rich hill). Potosí sits amid desolate mountains over 4,000 metres above sea level, yet by the early seventeenth century it was the fourth largest city in Christendom, because it was (and still remains) the largest known silver deposit in the world. According to Juan de Matienzo, a contemporary Spanish jurist, Potosí was 'a most beautiful mountain; there is none other that comes near to it'. To Domingo de Santo Tomás, a Franciscan missionary, it was 'a mouth of hell into which a great mass of people enter every year and are sacrificed by the Spaniards to their God'.

Conditions for the miners at Potosí were horrific. Paying wages wasn't enough, so the Spanish introduced la mita, forced labour, and then resorted to importing African slaves by the thousand. Between the mercury poisoning, the perilous descent down shafts hundreds of feet deep, rockfalls, and the sheer back-breaking labour required to haul the sacks of ore up to the surface, mortality rates were brutal: Dominican chronicler Rodrigo de Loaisa wrote that 'if twenty healthy Indians enter on Monday, half may emerge crippled on Saturday'.

Potosí quickly became one the largest cities in the Spanish empire as this site alone yielded 45,000 tons of pure silver over the the following centuries, a major contributor to the seemingly inexhaustible flow of treasure over the Atlantic to Seville, and valer un potosí still means 'worth a fortune' in Spanish. A fifth of all production went straight to the Crown (and a great deal more besides in taxation on private revenues), and the Spanish real de a ocho, a silver 8-real coin minted from 1598, became the first widely-used world currency owing to the consistency of its production and purity. While the world 'dollar' derived from the German thaler, it is this Spanish dollar that the independent United States would later base their own currency upon, and the real de a ocho remained legal tender in the USA until 1857.

This unlimited line of credit underwrote the vast territorial expansion of the Spanish empire in the sixteenth and sevententh century, financing its wars in Flanders, its wars in France and its ongoing conflict with England. It buttressed Philip II's status as 'Most Catholic King', defender of the faith against Protestantism in the Low Countries and repelling Islamic incursion from the south. The victory of the Holy League, commanded and largely financed by Spain, over the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto in the Mediterranean in 1571 established Spanish supremacy at seas, although the Ottoman Turks continued to threaten the borders of Christian Europe until a final decisive defeat at the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

And yet, the Armada was broken before it reached the shores of heretical England, and the Dutch Republic defied Spain's efforts to suppress its ongoing rebellion, at enormous cost. For all its literal mountains of treasure, the Spanish Crown defaulted on its debts many many times over (in 1557, 1560, 1575, 1596, 1607, 1627, 1647, 1652 and 1662), while falling silver costs and inflation further eroded its financial strength. Spain was afflicted by a resource curse that saw living conditions fall even as the treasure fleets came and went. Rent-earning aristocrats preferred to invest their surplus capital in government bonds to finance European wars rather than putting them towards any domestic improvements, and rigid central control over the colonies stifled any chance of political or economic development in the Americas: Spain was simply too dependent on the New World, as these were the only foreign dominions that did not ultimately drain the Spanish exchequor. The difficulty,

wrote historian Benjamin Woolley, was the Spanish empire itself. It ruled Spain as much as Spain ruled it.

Spain's vast legions contained few Spaniards, and her dominions were for the most part run by local administrators with a closer eye on their own interests than those of far-flung Madrid. Ruling the world was, it turned out, almost unimaginable complex, difficult, and expensive.

When Philip III succeeded his father in 1598 Spain was at war with France, England and the Netherlands. Piracy beset the Atlantic fleets, debts had just been renegotiated again to stave off further default, and plague devastated the economic heartland of Castile. It was in this international context that the Council of State, although alerted to another English plan to send settlers to the New World as early as 1606, ultimately chose to ignore the 'direct threat of an avowed enemy' upon their uncontested possession of the Americas. This was partly down to their uncertainty over where exactly Virginia was, but more attributable to the increasing impossibility of garrisoning an entire hemisphere while the European situation worsened. Don Pedro de Zúñiga, Spain's Ambassador in London, urged Philip to 'give orders to have these insolent people quickly annihilated', but the King continued to procrastinate, unwilling to provoke another costly foreign entanglement or risk the tentative peace between England and Spain.

Why, after all, should Spain care about England's east coast colonies? Spanish explorers had searched deep into the North American interior, but found nothing that warranted the effort. Mexico and Peru were a treasure trove of gold and silver, and the plantations of Central and South America a rich secondary income stream, sugar from the Caribbean and later tobacco, coffee, and indigo as well as other locally-traded commodities. The west coast was of far more value, for they were still looking for that new Silk Road, a westward route to the Indies. Acapulco was founded on Mexico's Pacific coast in 1550, and from there Spanish ships struck into the setting sun, finding the Philippines and opening a Manila-Acapulco trade route by 1565, carrying New World silver to China and returning with porcelain, silks and spices for Spain.

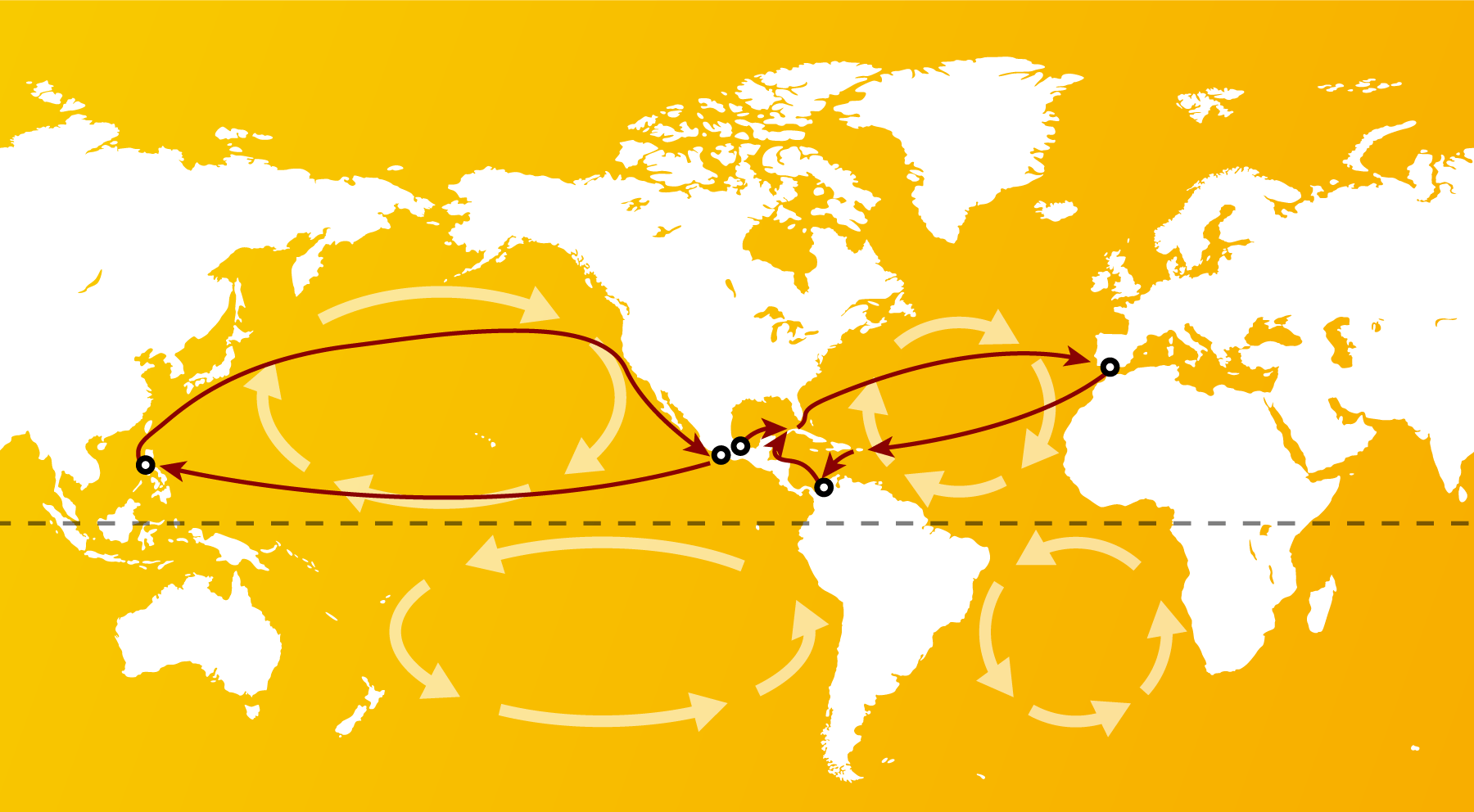

Protecting this trade was Spain's overriding priority. This meant fortified harbours in the Caribbean, most crucially at Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo where vessels from Spain were welcomed, and at Havana, their departure point for the return journey, a staging post for silver and gold from Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias. Ships arrived and left from different points because the prevailing winds and currents favoured a more equatorial route westward, and a more northerly path back. The Earth's rotation is fastest at the equator, and here the land moves eastwards faster than the air, meaning a relatively westward flow of air, and this winds creates corresponding currents, a clockwise flow in the northern hemisphere and a counter-clockwise one to the south. It was these northerly currents back from the Philippines that drove the Spanish settlement up the west coast of North America: they had reached San Diego Bay by 1540, and sailed as far up as Alaska long before the English had set foot in Jamestown. Control of this coast was essential for protecting their shipping from the Indies. Control of the east was largely irrelevant, at least so long as they held Florida.

Gold, trade, tillage represent the three stages in the history of colonization, and the greatest of these, because fundamentally essential to permanence, is tillage.

Charles M. Andrews

The story of the seventeenth century was one of gradual but irreversible European decline. From negotiated truces with the Dutch and revolt in Milan and Naples, through falling silver imports and a declining birthrate at home, to an uprising in Catalonia and the loss of Portugal, the tide had turned and the waters kept on rising. Eighty years of warfare in the Netherlands finally came to a close with the recognition of an independent Dutch Republic in 1648, the Thirty years War in Europe (1618-48) and defeat in the Franco-Spanish War (1635-59) put an end to Spain's supposed invincibility on the battlefield. In 1665 the three-year-old Charles II, the last Spanish Habsburg, became King, a monarch whose severe disabilities and inability to control his Court only hastened the impression of inexorable decline. Summed up as 'short, lame, epileptic, senile and completely bald before 35, always on the verge of death but repeatedly baffling Christendom by continuing to live' by historians Ariel and Will Durant, he ultimately died without an heir in 1700 bequeathing only further war to his enfeebled nation.

The Golden Age was passed, France ascendant, and Catholicism in retreat throughout North and Central Europe. The French Bourbons who claimed the Spanish throne in 1713 quickly applied their successful model of strong executive control over the navy and trade, and established a string of successful trading companies. The eighteenth century was one of growing prosperity at home and abroad, backed up by robust defence of the American colonies against attacks by the British and even a partial reversal of fortunes in Europe. Naples and Siciliy were recovered in 1734, and the British soundly repulsed in the magnificently-named War of Jenkin's Ear (1739-42), during which a British fleet greater even than the famous Armada was defeated at the Battle of Cartagena de Indias. The Louisiana territories were seized as spoils from France at the end of the Seven Years War in 1763, and a string of missions built up the Californian coast between 1769 and 1833 as the Spanish sought to assert their claims to the American North-West. On paper the Spanish Empire at its zenith in 1790 claimed all of modern-day Latin America apart from Brazil and the entirety of North America west of the Mississippi up to Alaska, a far greater geographical domain than England's Thirteen Colonies and Canada combined. The Spanish also played apart in ejecting England from those colonies, supplying and funding the revolting colonies through the English blockade, and arming and equipping the American forces that won at Saratoga. In 1779 the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Bernardo de Gálvaz, belatedly launched Spain's direct assault on the British Americas, ultimately expelling the British from Florida in 1781.

Spain's fall from grace, if it is to be so described, was a gradual one. Their New World monopoly was shattered, succeeded by a scramble between European powers, most notably the French, the Dutch, the English and the Russians, but for sheer breadth of American territory the Spanish empire was unrivalled, as yet unsurpassed. It brought Spain neither power nor prosperity, and for much of the eighteenth century parts of the empire flourished more so than the motherland, but it endured: it was there before the British, and it remained after the British had gone. The end, a long time coming, happened quickly. Napoleon Bonaparte, intent upon rebuilding New France after his rapid conquest of mainland Europe, took Louisiana in 1800, offering vague Italian possessions by way of compensation, but the French invasion of the Iberian peninsula in 1808 saw the rapid abdications of King Carlos IV and his son Ferdinand VII. A wave of wars and independence struggles between 1811 and 1829, often supported by indigenous Catholic landowners, stripped Spain of her mainland colonies. The Spanish-American War in 1898, in which Cuba was lost and Puerto Rico, Guam and the Philippines were seceded to the United States for a derisory $20 million, wrote the final chapter. On 2 June 1899 a Spanish battalion of infantry left Aurora in the Philippines, and wrote the final chapter to the adventure Columbus had begun over four centuries earlier.

They left their mark though. Over 400 million people in the Americas speak Spanish to this day, over 50 million of whom live in the United States, which has the second-largest Spanish-speaking population in the world (after Mexico). There are more Roman Catholics in Brazil than any other country, followed by Mexico, the Philippines, and the United States, with Italy squeaking into the top five. Many national borders in Latin America reflect the Spanish jurisdictional boundaries, while the Spanish dollar became the first currency to go truly global. Many of the greatest and most populous cities in the Americas were founded by the Spanish (including San Diego, San Antonio, San Francisco and Los Angeles), and St Augustine remains the oldest continuously-populated city in the United States. Culture, food, music and fashion all reflect and are built upon the Spanish legacy, indeed a common Hispanic identity has grown increasingly strident and proud throughout Latin America, often as a counterweight to influence from the United States. Since its gradual re-engagement with the international world after the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975 Spain has invested huge sums into Latin American economies, and regular international summits loosely akin to the British Commonwealth maintain the old imperial relationships on a more egalitarian and mutually-beneficial footing. "The past is never dead", and the Spanish in the New World are living in greater numbers and thriving more so than ever.

…if its great conquest have reduced this [Spanish] Monarchy to such a miserable condition, one can reasonably say that it would have been more powerful without that New World.

Count Duke of Olivares, 1631

Bibliography

- Brogan, H. (2001) The Penguin History of the United States of America (2nd ed.), London, Penguin.

- Durant, A. & Durant, W. (1963) Age of Louis XIV (Story of Civilization), TBS Publishing.

- Encyclopedia Virginia (2012), Letters between King Philip III and Don Pedro de Zúñiga (1609–1610)

- Ferguson, N. (2008) The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World, New York, Penguin.

- Goldman, W.S. (2011) 'Spain and the Founding of Jamestown' The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 68, no. 3, pp.427‑450

- Israel, J. (1977) 'A Conflict of Empires: Spain and the Netherlands 1618-1648' Past and Present, vol. 76, pp34‑74

- O'Flynn, D. (1982) 'Fiscal crisis and the decline of Spain (Castile)' The Journal of Economic History, vol. 42, no. 1, pp.139‑147

- Pagden, A. (1995) Lords of All the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France C. 1500-c. 1800 (2nd ed.), Yale, Yale University Press.

- Pueyo, T. (2021) A Brief History of the Caribbean, Uncharted Territories, Substack

- Woolley, B. (2007) Savage Kingdom: the True Story of Jamestown, 1607, and the Settlement of America, Harper Perennial, New York.