The self-made man

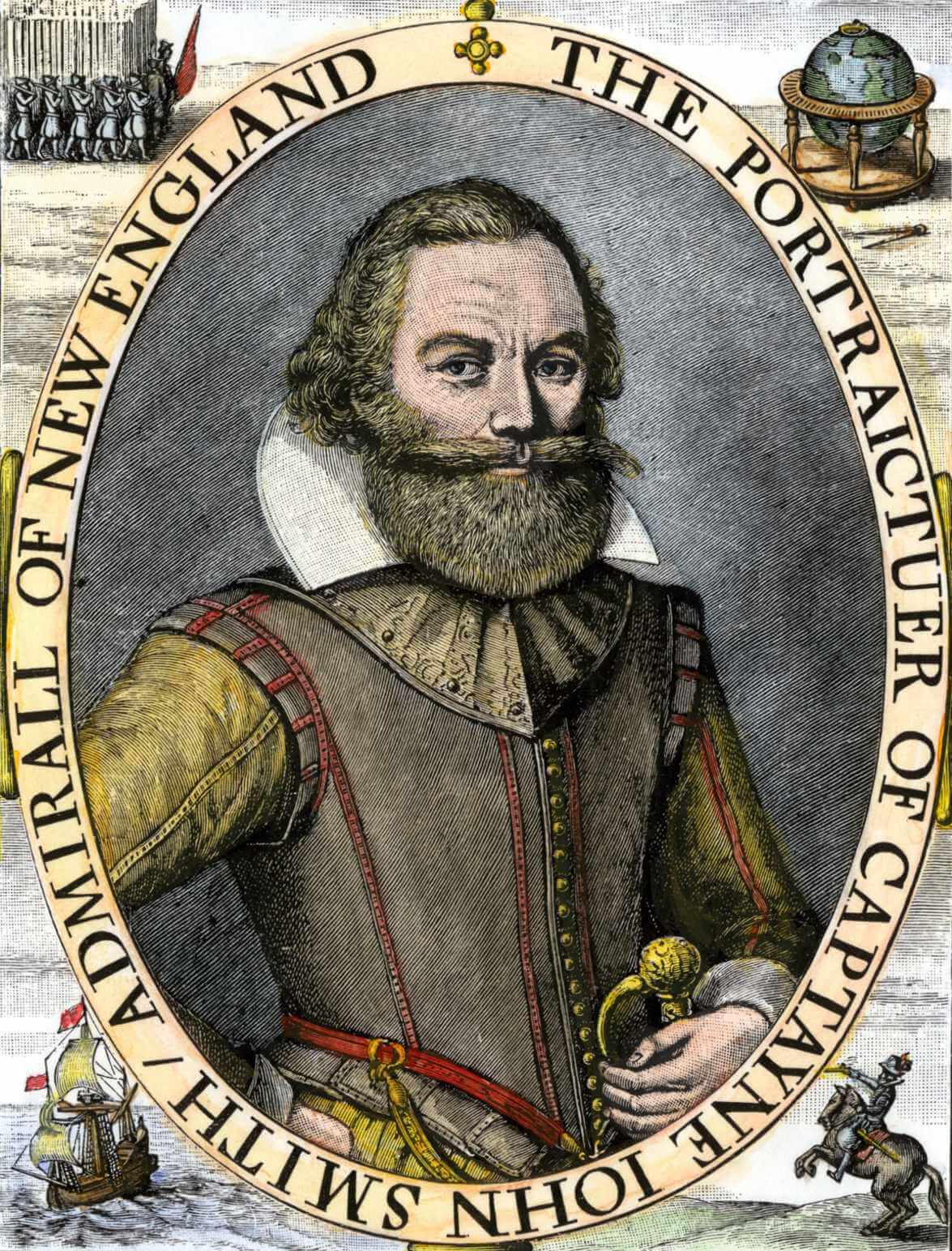

John Smith

Born c.1580, Lincolnshire, England | Died 1631, London, England

Soldier, Explorer, Cartographer, Author, President of Jamestown, Admiral of New England

You must obey this now for a law, that he that will not work shall not eat (except by sickness he be disabled). For the labors of thirty or forty honest and industrious men shall not be consumed to maintain a hundred and fifty idle loiterers.

John Smith

John Smith sounds like a made-up name (albeit a particularly unimaginative one). And John Smith's life sounds like a made-up life. But, unusually for a lead character in a Disney cartoon, he was real. We know so, from the number of people he managed to annoy. And not just ones who met him.

John Smith's most enduring success, his most significant achievement, was to save the fledgling Jamestown colony, and all who lived there, from starvation, for which his successor as President, George Percy, described him as an ambitious, unworthy and vainglorious fellow

. This judgement has endured, not least thanks to Smith's virtual canonisation of himself in his autobiographical works. He was a larger than life character, and the fact that he is not a more prominent historical figure can probably be attributed to his abrasive character, the fact that American historiography has traditionally chosen to favour the Pilgrims over the more materialist (and just a little bit cannibal) Jamestown settlers, and also his really, really boring name.

John Smith's life was the stuff of swashbuckling pulp fiction. He left England at 16 to spend a few years fighting in the Low Countries, then returned to live alone in the Lincolnshire woods studying and learning combat (studying for a while with the more magnificently-named Theodore Paleologue, the riding master at nearby Tattershall Castle, a descendant of the family of the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI who had died when the Ottomans took Constantinople in 1453). Leaving England again in 1600 he was captured by pirates and marooned, rescued, became a pirate, fought in the armies of the Holy Roman Empire against the Turks in Transylvania, had his horse cut down from under him at Alba Regalis, fought and killed three Turks in single combat on the Plains of Regal (for which he was awarded a title and his own coat of arms), captured, ransomed, and sold as a slave in the markets of Axiopolis, was taken to Constantinople to serve a rich Turk's mistress, sent to Russia to serve her brother, killed his new master and escaped on horseback, made his way back to Transylvania, then across Europe, was attacked by pirates again, and finally returned to London in 1604. This was all before he was 25. Before he did any of the things for which he is famous.

It remains something of a mystery how Smith came to be on the first ruling council of Virginia. He was acquainted with Bartholomew Gosnold, a prime instigator of the Virginia Company's endeavour, and was involved in the planning and funding of the venture as far back as 1605. Nevertheless he was a man of humble wealth and social standing compared to the other leaders, and he had managed to get himself charged with mutiny and almost hung while still en route to the New World. And when the sealed box containing the composition of the new Council was opened, the other six members refused to accept Smith's place among their number.

So, nomination notwithstanding, Smith remained in confinement, railing against President Wingfield's early decision not to build defences around the settlement. The Council had been instructed to have Great Care not to offend the naturals if you can Eschew it and employ some few of your Company to trade with them

. Smith could cause offence in an empty room, but as the sicknesses and deaths took their toll his colleagues had no choice but to use him. He joined Newport on scouting missions upriver, was admitted to the Council and, after Gosnold's death in August 1607, joined with Johns Ratcliffe and Martin to depose the elderly Wingfield: by September 46 colonists had died, be it from hunger, fever, or arrows fired at the settlement by their neighbours. Wingfield was accused of hoarding food, and Smith unsurprisingly nursed a grudge after his long incarceration, so Ratcliffe succeeded and Smith was elevated to the position of 'cape merchant', which meant responsibility for works on Jamestown and also for trade with the natives.

Although early exchanges with the native tribes had been hostile, it was increasingly clear to the native chief Wahunsenacawh from Jamestown's pitiful state that the colonists posed no immediate danger. And there were other threats, both rival tribes to the north and the Spanish in the south, against which an alliance with the English and their metal tools, their guns, might prove propitious. So when the harvest came to be gathered, the Powhatan were ready to trade. Smith, loathe to betray the settlement's weakness and desperation, took a hard line with mixed results, trading goods and provisions as well as musketfire with nearby tribes. In the course of his often reckless endeavours he was captured, whereupon he managed to impress the natives with the 'magic' of his compass and other learned revelations

.

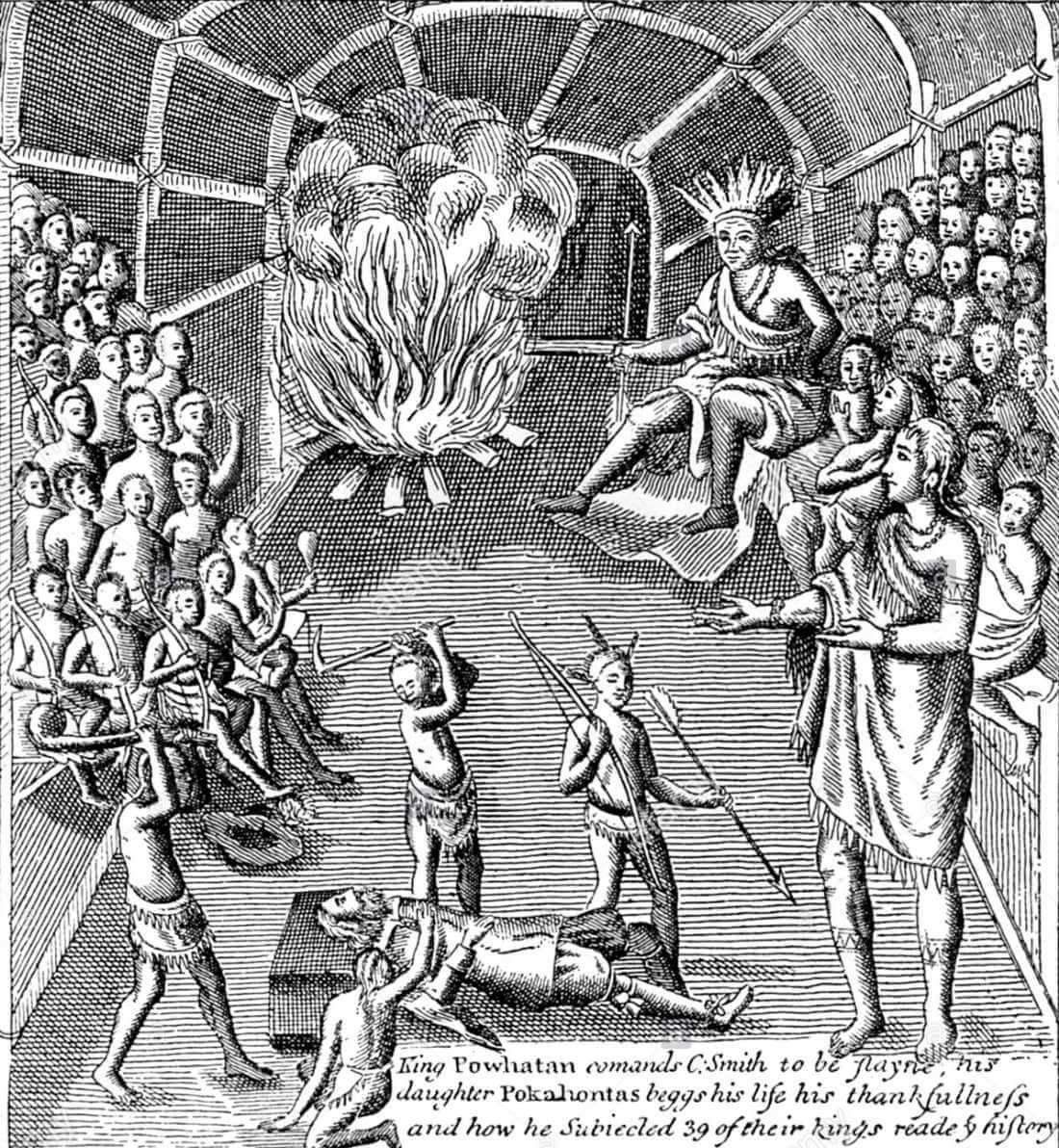

Smith remained a captive for many weeks as he was taken around various native towns and encampments, until he eventually met the great chief Wahunsenacawh (also referred to by the name of the confederacy, Powhatan). Smith managed to negotiate an understanding of sorts with Wahunsenacawh, which isn't to say that the chief didn't, like many of Smith's acquaintances, try to have him killed. One of these occasions, related by Smith years later, saw him saved at the last minute by the dramatic intervention of the chief's young daughter…

Smith was then dragged to one of the rocks, and the guards held hid head over it like an infant's over a font, the sprinkling of holy water to be a deadly rain of blows. It was in this vulnerable position, expecting death, that he first beheld the peerless beauty of Powhatan's twelve-year-old daughter, Pocahontas. She was a nonpareil, her features and proportions exceeding all the rest of her people. When no entreaties would prevail with the King to save Smith, she ran to the stone upon which Smith's head was about to be dashed. She clasped his head in her arms, and laid her cheek upon his, to save him from death…

John Smith

This is one of the founding fables of American history, celebrated in the frieze running around the dome of the Capitol building. Some have suggested it was not as Smith perceived, that the whole ceremony was an elaborate piece of theatre designed to intimidate or initiate him into the tribe. Others have gone so far as to describe it as pure fabrication, falsehoods of an effrontery seldom equaled in modern times

according to historian Henry Brooks Adams, though to boast of being saved by a young girl is an odd plot twist when set beside the Captain's more taditional tales of personal strength and daring. He was ultimately returned to the Jamestown camp on 2 January 1608, whereupon he was tried (again), sentenced to death (again), and a noose thrown over a handy tree branch (either for suspected collusion in the deaths of his comrades, for suspected sexual improprieties during his captivity or, well, just because it was a Wednesday): only the sudden return of Captain Newport from another supply mission to England saved Smith from the gallows.

Smith met with Wahunsenacawh on further occasions, and Pocahontas was a frequent visitor to Jamestown when food supplies were delivered. He also undertook another great voyage around the Chesapeake Bay, producing a great map of Virginia as he searched for the great water beyond the mountains

(probably one of the Great Lakes rather than the Pacific as they hoped). In September 1608 he became president of the colony (by this point Gosnold was dead, Kendall executed, Ratcliffe was imprisoned and Wingfield, Newport and Martin were in England), instituting an authoritarian regime in which all were expected to work or else starve. The storehouse and church were repaired after an earlier fire, and the defences all around strengthened. He managed a fractious relationship with the Powhatan: one time he negotiated his way out of an impasse by challenging Opechanacanough (the chieftain's brother) to single combat, then taking him hostage at pistol point when he demurred. Faced with another famine he ordered the settlers to disperse, riding his luck and the uneasy peace and ordering them to live off the land or the seafood in the bay.

When half of the May 1609 relief armada arrived in Virginia that August they were unimpressed with the mean and dispersed state of the camp, and old enmities immediately undermined Smith's position. Authority began to break down as one faction determined to found a new colonial capital, and while sleeping on his boat overnight as he journeyed back from an expedition upriver Smith was almost killed when his gunpowder belt managed to ignite, blasting away a substantial portion of his lower torso and thighs and setting him on fire. Taken back to Jamestown, he survived (by his own account) one more desultory assassination attempt before sailing back to England in October 1609. He never returned to Virginia.

Back in England Smith published his Map of Virginia With a Description of the Countrey in 1610, and wrote further volumes covering a later exploration of the New England coast as well as self-aggrandising accounts of the Virginia colony in which he painstakingly settled scores and dished dirt on his former rivals and antagonists. He attempted to raise funds for a New England (a region Smith himself named) colony, but had one endeavour scuppered by storms and another by pirate attack. He met Pocahontas again in England when she visited with her husband John Rolfe, albeit belatedly, and she chose to rebuke him for his supposed betrayal of his fealty to her father. The Pilgrims bought his charts and notes to plan their own expedition, but drew the line at the man himself: nevertheless when they ultimately reached America some two hundred miles north of their intended landing point, they chose an alternative, a location described by Smith as being blessed with an excellent good harbour, good land, and no want of anything but indstrious people

, which they named Plymouth.

Smith was, and remains, a divisive figure, for what he did and even more so for what he said he did, for he was always an ambitious and creative self-publicist. His early adventures are impossible to historically verify and many contemporaries and historians have questioned their truthfulness - a thinly-veiled satire, The Legend of Captaine Jones, penned by a Welsh clergyman in 1631 proved so popular it was reprinted many times over, and a sequel published in 1648.

Does it matter what Smith did or did not do? To the people he saved, or killed, inspired or enraged, yes, but to the bigger picture, the historical narrative? Much of history, from the Bible through the lives of saints and books of martyrs, has been the history of great men (The history of what man has accomplished in the world, is at bottom the History of the Great Men who have worked there

, said Thomas Carlyle in On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History). Heroic biography (and, increasingly, antiheroic biography) remains a mainstay of popular history (which isn't to say that Smith was a hero), but the academic emphasis has long since shifted to broader economic and social change, to histories of groups and ideas. The times made the men (and they were almost always men) rather than the reverse. A life can still illustrate the times, in a more immediate and relatable way than numbers, trends and abstractions ever could, but only with the attendant risk of over-emphasising the individual in question, of making the political (and everything else) personal. An individual might be used to represent an idea or a movement (a Washington, a Churchill or a Hitler), but much is lost in the reduction and this perspective often becomes, in Lucy Riall's phrase, an exercise in praise or blame

.

We come not to bury Smith, nor to praise him. Both are redundant. His early encounter with Pocahontas is part of the national myth, however you interpret myth. He had a starring role in the story of a small group of Englishmen perched precariously on the edge of an unknowably vast continent, a group whose struggle to survive could just as easily have gone the way of so many failed colonies before them, except that it didn't. He had little time for the Company's dreams of easy riches (There was no talk, no hope, no work, but dig gold, wash gold, refine gold, load gold

), but his exploration, his maps and his observations of the country, its environments and its peoples evidenced a faith in a larger, longer, more meaningful English purpose in America. The line that separates history from his story is a hazy one, and the more colourful narratives tend to stray outside the lines a little here and there. We just can't always know precisely where.

…sometime President there, made a map, and wrote a book.

Stowe's Chronicle

Bibliography

- Brogan, H. (2001). The Penguin History of the United States of America (2nd ed.), London, Penguin.

- Firstbrook, P. (2014). A Man Most Driven: Captain John Smith, Pocahontas and the Founding of America. London, Oneworld.

- Gookin, W. (1950). 'The First Leaders at Jamestown.' The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 58(2), 181-193.

- Hakim, J. (2003) Making Thirteen Colonies - 1600-1740 (3rd ed.). New York, Oxford University Press.

- Riall, L. (2010). 'The Shallow End of History? The Substance and Future of Political Biography.' The Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 40(3), 375-397.

- Wooley, B. (2007). Savage Kingdom. The True Story of Jamestown, 1607, and the Settlement of America. New York, Harper Perennial.