Go west, young man

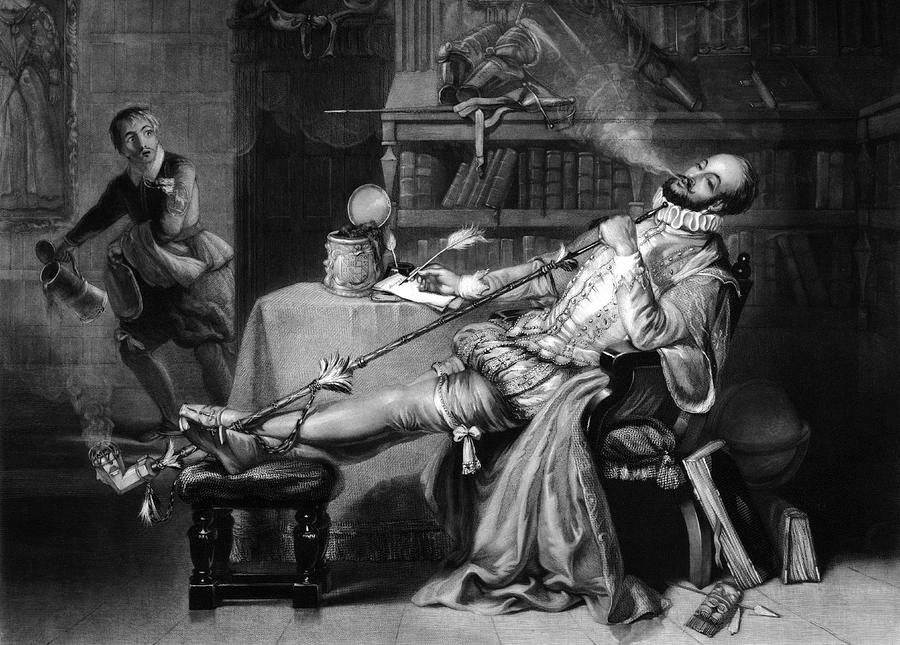

Sir Walter Ralegh

Born c.1554, Devon, England | Died 1618, London, England

Explorer and soldier, writer and poet, founder of the first English colony in the New World

For to posterity no greater glory can be handed down than to conquer the barbarian, to recall the savage and the pagan to civility, to draw the ignorant within the orbit of reason, and to fill with reverence for divinity the godless and the ungodly.

Sir Richard Hakluyt to Sir Walter Ralegh

Sir Walter Ralegh was a poet and a pirate. He was a writer and a politician, a soldier and an entrepreneur, a patriot and, it now seems likely, a traitor. To describe him as the founder of the British empire would be a step too far, but he certainly had the necessary qualifications. Ralegh fought the Spanish and stole from them, conspired with them, and was ultimately executed by King James at their behest. He founded colonies, which failed, and scoured the rivers of South America in vain for El Dorado. In the New World he saw rich and unknown lands, fatally and it seemeth by God's providence, reserved for England

, and was, perhaps, the closest the English came to a conquistador. Sir John Seeley suggested, in the late-nineteenth century, that England's empire had been acquired in a fit of absence of mind

, which is plainly nonsense. The nugget of truth in there was that while monarchs prevaricated and governments tightened their purse strings, it was men on the ground who made things happen, whether people wanted them to or not. There was no grand design, there were just men. Men like Walter Ralegh.

Ralegh never actually set foot in North America. He was born in Devon to a Protestant family, and their connections (his mother's aunt had been Queen Elizabeth's governess) secured his introduction to the royal court. After a short spell fighting with the Huguenots in the French wars of religion and a year at Oxford, he later joined the Middle Temple (one of the London Inns of Court that trained barristers). He was to spend much of the next two decades however in Ireland, where he took part in the campaigns againt the Desmond Rebellions of 1579-83 (which ultimately led to the plantation of Munster by Protestant English settlers), and was awarded 40,000 acres there as a result. Returning to court in the 1580s the dashing soldier and poet soon became one of the aging Queen's (many) favourites: he was knighted in 1585, served in the parliaments of 1585 and 1586, and was made Lord Lieutenant of Cornwall and Warden of the Stannaries (the tin mines) of Devon and Cornwall. He was part of Elizabeth's council of war charged with repelling the Armada, and took the lead in fortifying the coasts of Cornwall and Devon against the expected Spanish invasion. It might almost have been a footnote to such a glittering career that in 1584 he was granted the right to colonise America.

That 'right' wasn't as grandiose as it might sound. It was permission only, with no suggestion of royal sponsorship, much less financial support. This had previously been permitted to Ralegh's half-brother Sir Humphrey Gilbert (another veteran, indeed almost an instigator of, the Desmond Rebellions) to discover, search, find out and view such remote heathen and barbarous lands countries and territories not actually possessed of any Christian prince or people…

, but Gilbert was drowned near the Azores in 1583.

Ralegh adopted his brother's cause with relish. The English were no strangers to the New World by now, but they went there only to pursue a more parochial concern, their war against the Spanish: as Hugh Brogan concluded, Caribbean piracy was holy, lucrative, and for a long time easy

. Ralegh's vision went further, as outlined in the Particular Discourse Concerning the Great Necessity and Manifold Commodities That Are Like to Grow to This Realm of England by the Western Discoveries Lately Attempted, Written in the Year 1584, written by Richard Hakluyt under Ralegh's commission. Hakluyt was to become one of the most persistent and persuasive English advocates for plantation and settlement of the New World, and was a Director of the Virginia Company from 1589. He and Ralegh dreamed big, and promised even more, but initial results were disappointing. After an initial expedition in 1584 identified a likely site upon which to found a colony, on the island of Roanoke in North Carolina, settlers sent in 1585 hitched an early ride back with Sir Francis Drake after difficulties with the locals (albeit bringing maize, tobacco and, possibly, the potato with them). 115 new colonists were sent in 1587, but their reinforcements were delayed by the need to repulse the Armada, and by the time their Governor, John White, managed to return there in 1590 every man, woman and child had disappeared without trace (well, one trace, the word Croatoan carved into a fencepost, referring to a nearby tribe or island, but nothing was ever revealed of the Lost Colony's fate). Ralegh made some effort to solve this mystery, but his enthusiasm turned to more immediate rewards and he himself sailed for Guiana and Venezuala in 1595 in search of the legendary El Dorado, publishing an account of the voyage that boasted of a gold-rich empire more lucrative than Peru

. The Anglo-Spanish War of 1585-1604 sapped England's energies for anything beyond the quick win, and it would take another twenty years after the Roanoke debacle before a further attempt was made to settle Englishmen on new and distant shores.

England did not, in Ralegh's time at least, expect an empire. Whereas in later centuries imperial ambition would lead Great Britain into conflict with most similarly-minded European powers, Elizabethan England was rather led toward empire by European conflict, specifically the threat of Spain. The northern Americas might have seemed a natural area for English exploration, but fruitless quests for a northern passage to the Indies as well as Martin Frobisher's haul of Fool's Gold had led to a marked cooling of royal enthusiasm for these 'meta incognita' (as Frobisher had named the Arctic north when claiming it for England, meaning 'of limits unknown'). Elizabethan England's heroes were her privateers, seadogs rather than soil planters, and Ralegh, who sent colonists to the Americas, was far less feted than Sir Francis Drake, who brought them back home again.

Spain didn't want an empire either, it wanted the empire, the Last World Empire. The Spanish rulers, self-styled Kings of Jerusalem, aimed at nothing less than the redemption of Biblical prophecy, at the creation of the Fifth Kingdom (after those of Babylon, Persia, Greece, and Rome) that shall break in pieces and consume all these kingdoms, and it shall stand forever

(Daniel 2:44). It was the Habsburgs spreading the gospel to the New World, and the Hapsburgs that turned the infidel back from the gates of Europe when they halted the Turkish advance at Vienna in 1529 and later in the Mediterranean at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571. Their goal was nothing less than bringing the entire world (including heretical England) into the true faith, in fact from 1580 and the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns, Philip's motto was rather more ambitious: non sufficit orbis

, the world is not enough. For England and France, self-preservation in the face of this unchecked expansionism led them to a more libertarian philosophy encompassing the defence of civic liberties and native rights: rather than emulating Spain's policy of enslaving the indigenous populations the French focussed their more limited ventures on trade (mostly furs from the northernmost latitudes) while England's enthusiasm was for land upon which to grow and to settle their own surplus populace.

In part to define themselves against the Spanish 'Black Legend', England initially took the moral high road to empire. Their philosophy was based on the Roman notion of res nullius, that of empty and unclaimed lands, and their conquests were to be over nature, taming the wilderness and bringing it under the Biblically-mandated dominion of man. Treaty or purchase were the preferred means of dealing with natives' claims so that the English might dwell peacably among them, and where force might prove necessary to enforce 'natural rights', George Peckham's True Report of the Late Discoveries (1583) urged that it be prosecuted with as little discommodity to the Savages as may be

.

If you do not do this or if you maliciously delay in doing it, I certify to you that with the help of God we shall forcefully enter into your country and shall make war against you in all ways and manners that we can, and shall subject you to the yoke and obedience of the Church and of their highnesses; we shall take you and your wives and your children and shall make slaves of them, and as such shall sell and dispose of them as their highnesses command... and we protest that the deaths and losses which shall accrue from this are your fault, and not that of their highnesses, or ours, or of these soldiers who come with us.

Spanish Requirimiento

This theoretical benevolence contrasted sharply with the more practical experience of Elizabethan England's testbed for colonization: Ireland. Their ordinary food is a kind of grass

wrote official government minutes on Ireland in 1599: Neither clothes nor houses generally do they care for. With this their savage life are they able to wear out any army that seeketh to conquer them

. While Ralegh's reports of New World natives echoed those of Columbus in praising their gentleness and hospitality, the English viewed their nearer neighbours as altogether ignoble savages, cannibals, and worse still, Papists. The first New England Ralegh had pursued was in Munster, though he had little success in persuading English settlers to take root there. Nevertheless England persisted in displacing the 'wild Irish' and replacing them with Protestant planters throughout the seventeenth century, with as much discommodity as they liked: as Governor of Ulster Sir Humphrey Gilbert had ordered in 1569 that the heads of all those (of what sort soever they were) which were killed in the day, should be cut off from their bodies and brought to the place where he encamped at night, and should there be laid on the ground by each side of the way leading into his own tent so that none could come into his tent for any cause but commonly he must pass through a lane of heads which he used ad terrorem… [It brought] great terror to the people when they saw the heads of their dead fathers, brothers, children, kinsfolk, and friends…

. The English government would offer bounties on the heads of any Irish killed, subsequently paid on scalps, one of many practices trialled in Ireland and later enthusiastically exported to the American colonies.

Men like Ralegh and Hakluyt were ahead of their times. They talked of raising New Englands across the world, like a tree from whom plants have been taken to fill whole orchards

. They conceived of an England exporting her surplus population to colonies that would return an agricultural bounty freeing their motherland from dependence on agricultural imports, on Spanish olives and wine. And they hoped for a foothold in the New World from which to break Spain's hold and stem the seemingly endless tide of gold flowing into the Spanish King's coffers. What they delivered, in the 1580s at least, was deprivation and starvation, a 'conquest' of Virginia (as Ralph Lane, Governor of the first Roanoke colony boasted) that amounted to the construction of a makeshift fortified English village off the coast of North Carolina and, ultimately, the loss of every man, woman and child that stayed there. Elizabethan England had enough troubles with defending its borders to spare any energies for expanding them, and even after the peace with Spain in 1604 the crown had little inclination towards these dubious overseas ventures. Had it been otherwise, had King James and his successors pursued a more energetic and centrally directed program of territorial expansion and conquest, then the sporadic and unmanaged growth of a series of small American settlements on the Atlantic coast throughout the seventeenth century might have developed under a very different, far less heterodox, political and religious culture.

Ultimately Ralegh found himself behind the times, fighting old battles, and after attacking the Spanish settlement of San Tomé on the Orinoco River in 1616, still searching for those cities of gold, he was sentenced to death by King James and beheaded at Westminster in October 1618. By this time the fledgling Virginia Company of London, established in 1606, had managed to turn a profit (albeit a short-lived one) from New World plantations, and from a crop particularly close to Raleigh's heart – tobacco. The road to New England would not be as short, as straight, or as untroubled as Ralegh and Hakluyt had promised, but England was nonetheless firmly embarked upon it.

We shall by planting enlarge the glory of the Gospel… and provide a safe and sure place to receive people from all parts of the world that are forced to flee for the truth of God's Word.

Richard Hakluyt

Bibliography

- Brogan, H. (2001) The Penguin History of the United States of America (2nd ed.), London, Penguin.

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne (2003) 'The Grid of History: Cowboys and Indians' Monthly Review vol. 55, no. 3.

- Kupperman, K. O. (2015) 'Before 1607' The William and Mary Quarterly vol. 72, no. 1, pp. 3-24.

- MacMillan, K. (2011) 'Benign and benevolent conquest? The ideology of Elizabethan Atlantic expansion revisited', Early American Studies vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 32-72.

- Mumford-Jones, H. (1942) 'Origins of the colonial idea in England', Proceeedings of the American Philosophical Society vol. 85, no. 5, pp. 448-465.

- Pluymers, K. (2011) 'Taming the wilderness in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Ireland and Virginia' Environmental History vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 610-632.

- Williamson, A. (2005) 'An empire to end empire: the dynamic of early modern British capitalism', Huntington Library Quarterly vol. 68, no. 1-2, pp. 227-256.