Christening America

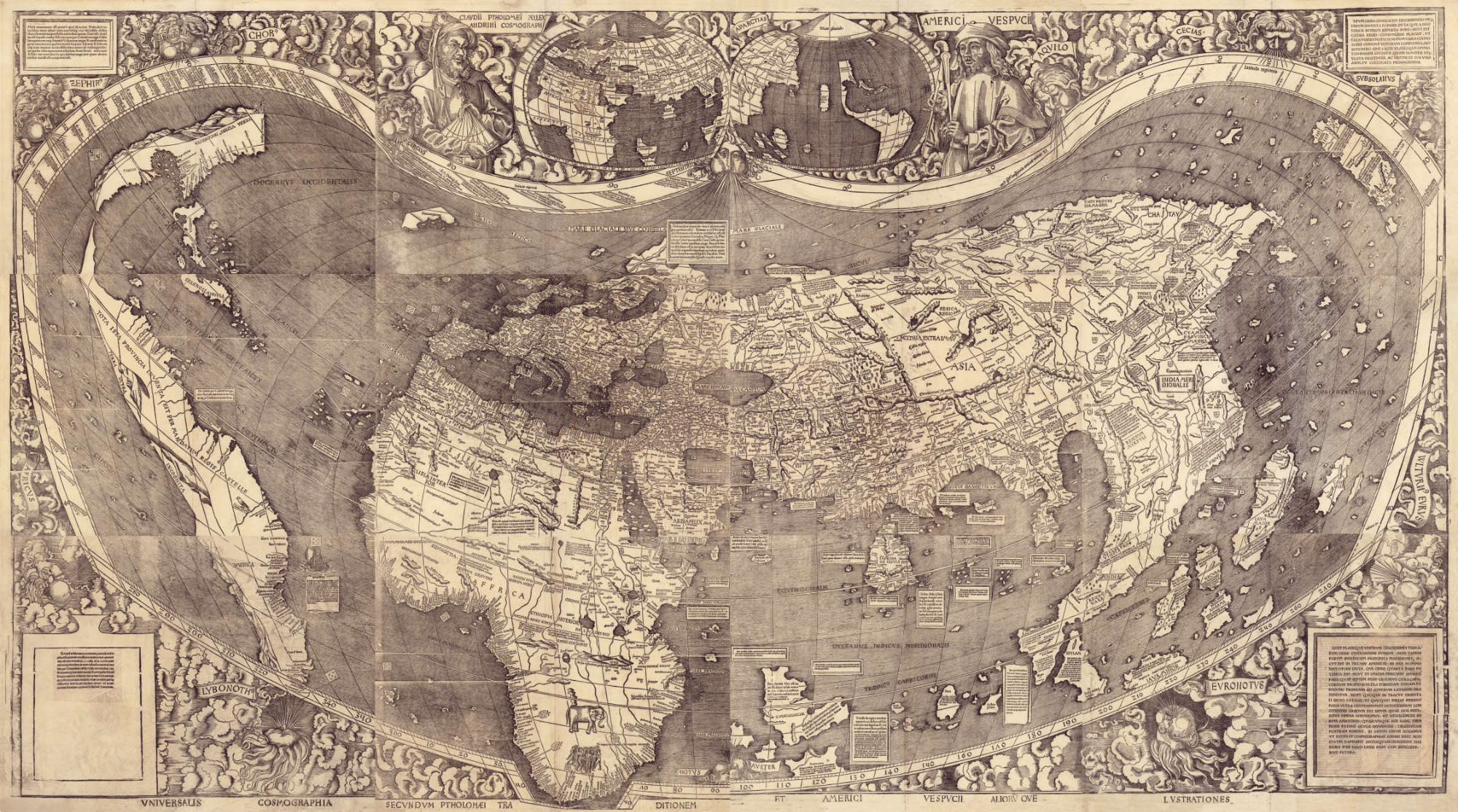

Martin Waldseemüller's world map

Those new regions which we found and explored with the fleet... we may rightly call a New World... a continent more densely peopled and abounding in animals than our Europe or Asia or Africa; and, in addition, a climate milder than in any other region known to us.

Amerigo Vespucci

For better and for worse, the name of Christopher Columbus is forever linked with the discovery and conquest of the New World, and yet the vast dominions opened up by his voyages of discovery, two continents worth, bear another man's name. Specifically, that of Amerigo Vespucci (‘Americus’ in the Latin), an Italian merchant, mapmaker and writer whose widely-published letters about his own later voyages to the new continent earned him an international reputation in the early sixteenth century.

Vespucci reputedly made four expeditions to the New World between 1497 and 1504, sailing further down the east coast of South Amwrica, past the Amazon and towards Patagonia, though with the aid of hindsight the details of his supposed discoveries suggest that some of those letters were either forgeries or else fabrications by Vespucci himself. His importance lies less in the small print however than the fact that he managed to popularise his main contention, that these new lands were a continent in their own right and not the eastern rim of Asia. While Columbus was still scouring the Caribbean in search of the Emperor of China, Vespucci asserted a bigger truth, that this really was Mundus Novus, a New World.

Thus was the map of the world redrawn, the first major update to global cartography since the Ptolomaic (after Greek scholar Claudius Ptolomy) projection of the second century ad. And the first map to depict this new geographical order (or at least the earliest that survives) was made by German cartographer Martin Waldseemüller in Saint-Dié, France, in 1507. Waldseemüller’s map was a huge 2.3m x 1.3m, printed via twelve separate wooden blocks. It innovated : it was the first map to portray the Earth as a globe (depicting all 360 degrees of the Earth's surface, much of it speculatively), the first to show the existence of these new continents, the first to incorporate the Pacific Ocean (a full six years before Spanish conquistador Vasco Nunez de Balboa confirmed its existence), and the first to accurately locate Japan (labelled Zipangri). It is also the first time the name of this New World ever saw print: America.

It may seem a bit much to name an entire hemisphere after one man (and there seems little doubt that Vespucci was that man despite alternative candidates, not least because Waldseemüller includes his name in the map’s title and even depicts him in one of the panels), and indeed when the Saint-Dié scholars published a new atlas in 1513 the name America was gone, replaced with Terra Incognita (unknown lands), but by then the name had stuck. It might seem that Columbus had a stronger claim to the honour, but then he’d blotted his copybook somewhat by persisting to believe that he has discovered the western shores of Asia and by arguing with the Spanish crown over those titles he already saw as his due. He also died in 1506, which quietened him down a bit.

This map and the accompanying book, Cosmographiae Introductio, were enough to embed this name in the popular imagination, even though Waldseemüller himeself abandoned it on later maps. Other contenders included Terra nova (new world) and Terra sanctae crucis (Land of the Holy Cross). Although 1,000 copies of the 1507 map were supposedly printed, only one remains. It was part of a portfolio maintained by a sixteenth century German globe maker, and was rediscovered in Wolfegg Castle in Baden-Württemberg, Germany in 1901. The Library of Congress purchased the map in 2003 and keep it on permanent display in Washington DC, entitled 'America's birth certificate'.

For the execution of the voyage to the Indies, I did not make use of intelligence, mathematics or maps.

Christopher Columbus

Bibliography

- Hebért, J. (2003). The Map That Named America [Online]. Library of Congress. Available at: https://www.loc.gov/loc/lcib/0309/maps.html (Accessed: 12 November 2018).

- History of the World in Maps (2014), Glasgow, Times Books.