In fourteen hundred and ninety two…

First contact

Christopher Columbus, as everyone knows, is honoured by posterity because he was the last to discover America.

James Joyce

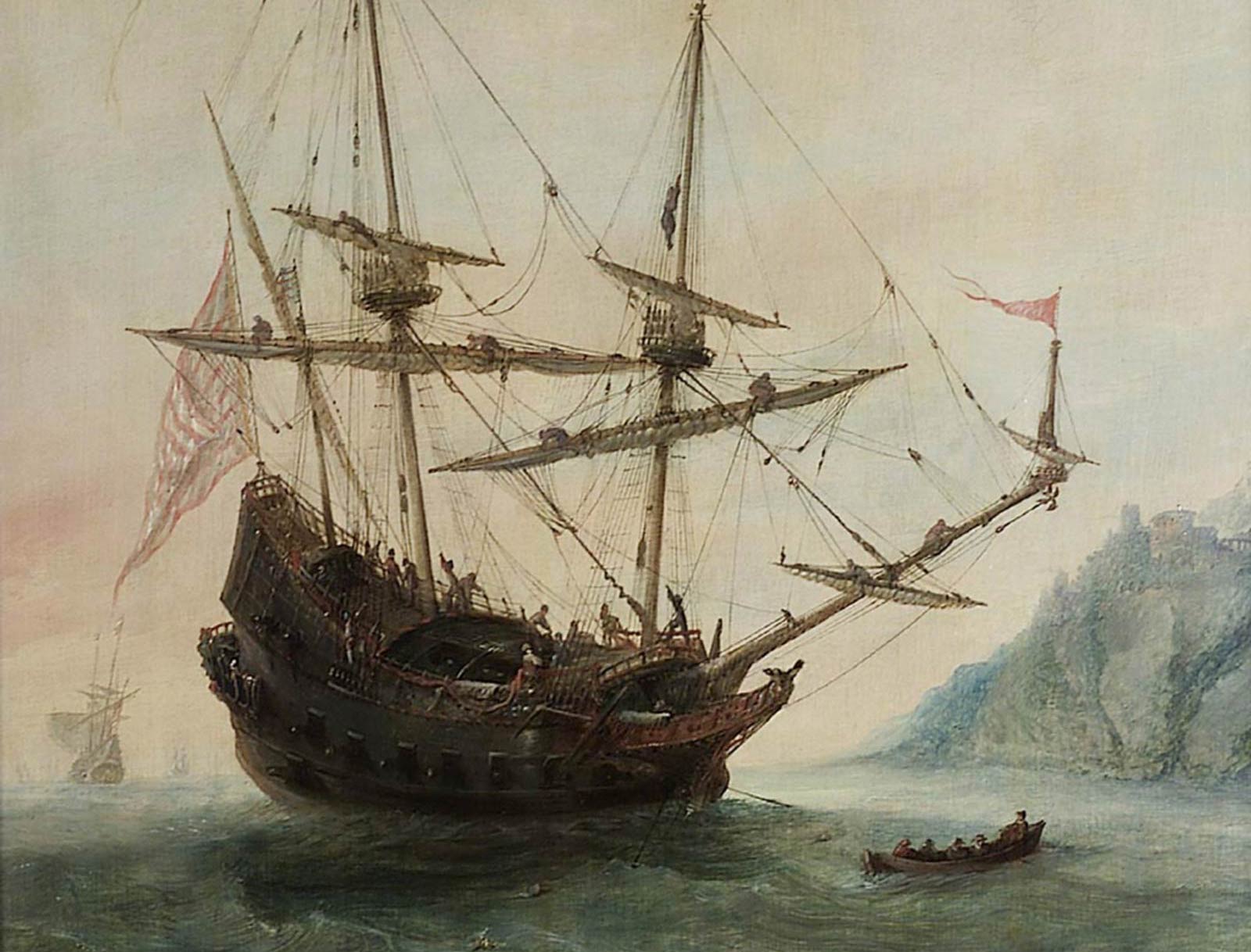

The ship’s deck was maybe sixty feet or so long, eighteen feet wide, and forty men called her home. Out on the open ocean they slept where they could, on deck for the most part, tied down in rough weather, unless the rain was so bad it drove them to seek what space there was to be found in the hold, which grew only more filthy and foul-smelling as the weeks passed by. They ate rice and hard biscuits, soaked in water to make them some way edible, and big stews of poorly-boiled meat or fish with chickpeas and beans. But there was cheese too, and honey, olives and raisins, and wine from the vineyards around Cadiz, cultivated over the centuries by Moors, Romans, and Greeks, all the way back to the early Phoenician colonists. So it wasn’t all bad.

And they were making history, these men. Their captain promised it. As well as riches. Their captain promised those too. A westward route to the Indies, to the wealth and wonders of the Orient. Ninety or so men sailing into the unknown, on three ships, off the edge of the maps, because their Captain said the Indies lay three weeks west of the Canaries. Their Captain had studied the trade winds and calculated the distance, and set out to do what no man had done before. Their Captain lied: he kept two log books, one to share with his crew, and one of his own, that showed how far they had really come, how far they really had to go, for he did not trust them not to mutiny if they understood the true distance involved. Their Captain was a liar, and worse, he was wrong. It was further, much further than he thought. They were all going to die.

But their Captain, Christoforo Colombo, was one thing more: he was lucky. The Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa Maria never found their westward passage. They found something else. At two o’clock in the morning of 12 October 1492 they discovered a new world when Rodrigo de Triana, a lookout on the Pinta, spied shore (probably that of San Salvador, Samana Cay, or Plana Cays, all situated some 250-300km north-east of Cuba though the precise location is unknown) in the Bahamas.

This is how the story begins. Not to Columbus of course, to whom America meant nothing. So far as he was concerned, he'd made it, and opened up a new and lucrative trade route from Europe to the spices and gold of the Far East. Spain’s Admiral of the Ocean Seas (a title he earned for this masterpiece of misdirection) had traversed the Atlantic to reach the uncharted eastern shores of Asia, shores he immediately claimed for the crown of Castile. Governorship of these new lands, untold glory, and 10% of the profits would be his (a very generous agreement, so much so that we might imagine their Catholic majesties never seriously expected to see him again). What was America compared to this?

European explorers had once more beached upon the shores of the New World, and this time they were here to stay. It was the changing balance of power half a world away that had set Columbus out on this route. The shortest distance between Europe and the Far East had once been the Silk Road running from China through Central Asia via India and Afghanistan amongst others to Constantinople and the commercial metropolis of Rome. But the once-mighty Mongol Empire that guaranteed the safety of travellers was crumbling, while the fall of Constantinople (and with it the final vestiges of the Roman Empire) to the Ottomans in 1453 heralded a Middle East suddenly less welcoming to Christian merchants.

With overland trade inconvenienced, the great powers of Western Europe resolved to find alternative means of tapping the riches of the Orient. The Portuguese went south, around the horn of Africa, earning their fortunes in gold, ivory and slaves as they did so. The venture Columbus hawked around the royal courts of Europe was more reckless: go west. Too reckless for the Portuguese, the Genoese, the Venetians and the English, all of whom dismissed his petitions for royal sponsorship. The Spanish court too determined that he had wildly underestimated the distances involved, but elected to keep their options open by paying Columbus an annual allowance to retain first refusal on the scheme. The Catholic Monarchs Fernando II of Aragon and Isabella of Castile had united their lands in their marriage, and were just about to recapture Granada, completing their reconquest of Spain from the Moors (the Reconquista) when Columbus made his final pitch. Already past 40 years of age, his time was running out, and this time proved no different: the royal advisers again rejected the scheme as a vision, a fantasy.

A dejected Columbus was riding out of Granada by mule when he was waylaid by a royal messenger. Their Royal Highnesses had changed their minds: flush with success, they were ready to gamble that what they might lose paled into significance set against what they stood to win. The Treasurer of Aragon had argued that the sum required was trivial when set against the risk that the Portuguese might take this gamble and win. Fernando was set upon continuing the Reconquista all the way to Jerusalem, in the ambitious belief that he was The Last Roman Emperor, and dreamed of a westward Crusade to retake the Holy Land. To this end they would fund a carack and two caravels, light ships capable of sailing into the wind, and around ninety men to sail west into the impossibly vast unknown. On 3rd August 1492, from Palos de la Frontera on the south coast of Spain, they set off. It is likely that few thought they would ever return.

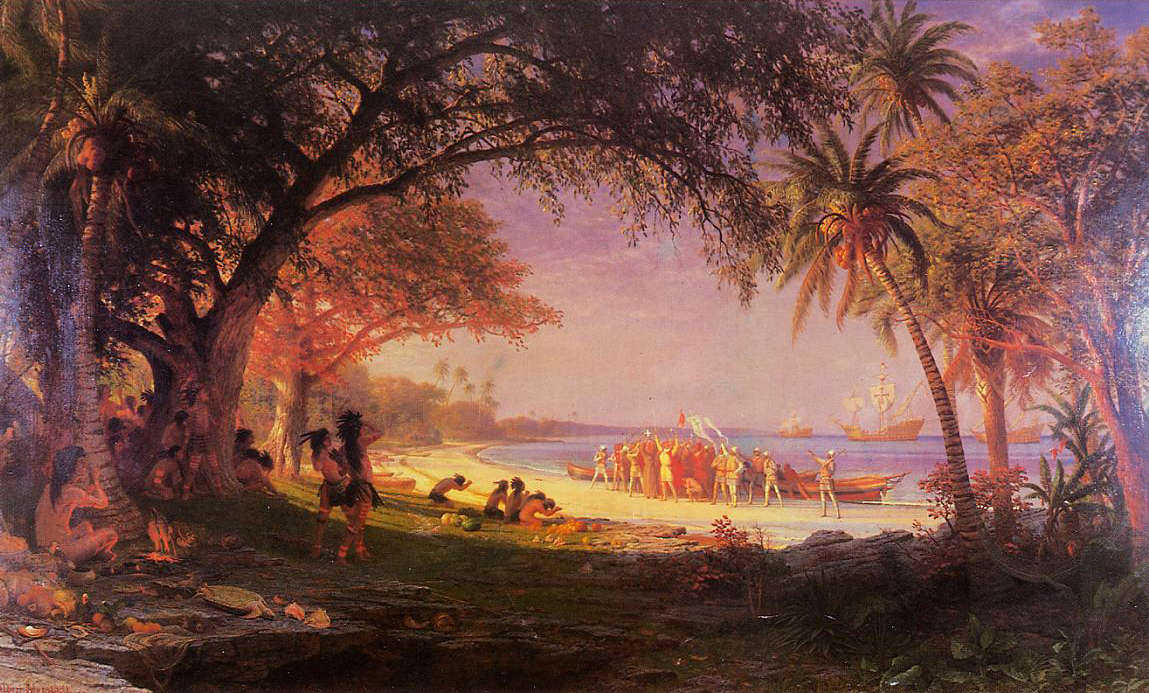

The Arawaks who saw these same three ships come sailing into harbour in Guanahani, as they called it, knew nothing of Catholicism, Crusades, Castile or the value of gold and spices to Europeans. All they saw was something they’d never seen before, and they swam out to get a closer look. Columbus in turn knew that he was seeing something unseen and unclaimed by any Christian prince, so claim it he did, for Castile, for Spain, and for himself. And like the first Christian, he gave names to all that he found: the island he called San Salvador, and the natives became Indians, one of history’s most enduring misnomers.

They [the Arawaks] willingly traded everything they owned … They were well-built with good bodies and handsome features… they do not bear arms and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane… They would make fine servants… With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

The Journal of Christopher Columbus

Entranced by all he saw, Columbus sailed on in search of the mainland and the coast of India. He landed next on Cuba (the peaks of which he mistook for the Himalayas) and Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic), where his flagship the Santa Maria hit a reef and foundered on Christmas Eve. From the timbers of his ruined vessel Columbus built the first European outpost in the Americas, the fort of La Navidad, in which he left 39 men to maintain trading relations with the Indians while he sailed back to Europe to bask in his triumph.

News of the discovery swept Europe, and despite the relatively tiny amount of gold he brought back, as well as a number of kidnapped natives, Columbus spun tales of miraculous lands abundant with ‘many spices, and great mines of gold’, promising his Spanish majesties ‘as much gold as they need … and as many slaves as they ask’. Such was the bounty on offer that a second expedition of seventeen ships and about 1,200 men was quickly launched on 3 November 1493.

Before it left however the Spanish sought to legitimise their claim with a Bull of Papal approval. The 1479 Peace Treaty of Alcáçovas that had settled The War of the Castilian Succession between the Catholic Monarchs and Afonso V of Portugal had granted all land south of the Canaries to the Portuguese (largely on the grounds that no-one had much use for them at that time anyway), subsequently confirmed by the Papacy in the 1481 Aeterni regis bull. The Portuguese had already passed on Columbus's insane venture, but upon his return (he made landfall in Portugal before he did in Spain thanks to a storm that blew him into Lisbon on 4 March 1493) King John II was immediately more mindful of his rights over undiscovered lands in the Atlantic.

Pope Alexander VI was a Spaniard, and moreover undergoing a spot of trouble with Ferdinand's cousin, the King of Naples, and was thus more than willing to extend the Spanish court every courtesy. Three bulls issued within two days undid Portugal's eternal kingdom with surprising speed: Inter Caetera (an impressive title meaning 'amongst other things') effectively granted to Spain any undiscovered (meaning unChristian) lands in the west. The Papal pronouncements were somewhat short on specifics however, so Spain and Portugal settled matters in the spring of 1494 with a treaty signed at the Spanish town of Tordesillas that divided the globe between them along a meridian (a line running from the North Pole to the South) halfway between the Portuguese Cape Verde islands and Columbus's discoveries. The world was theirs: they had but to reach out and take it.

Sailed this day nineteen leagues, and determined to count less than the true number, that the crew might not be dismayed if the voyage should prove long.